Reuters: The Mexican army says its fight against surging opium production that feeds U.S demand is increasingly complicated by the rise of smaller gangs disputing wild, ungoverned lands planted with ever-stronger poppy strains.

The gangs have engulfed the state of Guerrero in a war to control poppy fields, turning inaccessible mountain valleys of endemic poverty and famous beach resorts into Mexico’s bloodiest spots.

Colonel Isaac Aaron Jesus Garcia, who runs a base in one of the state’s most unruly cities, Ciudad Altamirano, told Reuters on an operation to chop down poppies high in the Guerrero mountains that violence increased two years ago when a third gang, Los Viagra, began a grab for territory.

Bodies are discovered almost daily across the state, tossed by roads, some buried in mass graves. In Ciudad Altamirano, the mayor was killed last year and a journalist gunned down in March at a car wash.

“These fractures (in the gangs) started two years ago, and that caused this violence that is all about monopolizing the production of the drug,” Jesus Garcia said.

From this frontline of the fight against heroin, Jesus Garcia sees a direct link between a record U.S. heroin epidemic that killed nearly 13,000 people in 2015 and violence on his patch.

“The increase of consumers for this type of drug in the United States has been exponential and the collateral effect is seen here,” Jesus Garcia said.

Heroin use in the United States has risen five-fold in the past decade and addiction has more than tripled, with the biggest jumps among whites and men with low incomes.

Jesus Garcia said the task of seeking out poppy fields in one of Mexico’s poorest and least accessible regions, rising above the beach resorts of Acapulco and Ixtapa, was practically endless.

His 34th Battalion and others send platoons of troops on foot for month-long expeditions every season. They set up camps and fan through treacherous terrain, part of a campaign that destroys tens of thousands of fields a year.

One such field visited by Reuters was deep in a lawless region six hours from Ciudad Altamirano through winding dirt roads thick with dust that rose into the mountains.

It was irrigated by a lawn sprinkler mounted on a pole that spritzed water over less than a hectare of poppies and fertilizer bags were piled nearby, basic farming techniques the soldiers nevertheless said were a sign of growers’ new sophistication.

A dozen troops fanned out, chopping down the flowers with machetes.

HIGHER YIELDS

Army officials said gangs use poppy varieties that produce higher yields and more potent opium from smaller plots, and that its higher value is driving violent competition between gangs.

“Now we see more production of poppy in less terrain, and it has to do with the quantity of bulbs each plant has,” said Lieutenant Colonel Jose Urzua as he showed bulbs oozing valuable gum from slits. He explained opium is often harvested by families.

In these tiny mountain hamlets opium has grown for decades, officials said, but a coffee plague and the U.S. opiate epidemic has led farmers to plant much more.

The harvest has become central to Guerrero’s economy, also dependent on cash sent home by immigrants.

One army official said the field seen by Reuters could produce around 3 kilos (6.6 lb) of opium, fetching up to $950 per kilo from traffickers who sell it for up to $8,000.

“There aren’t many alternatives here,” said a woman selling soft drinks and snacks from a pine shack by a dirt road. Her husband grows poppies, and she said anyone who runs a business faces extortion by gangs.

***  CNN

CNN

(CNN)It was the second deadliest conflict in the world last year, but it hardly registered in the international headlines.

As Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan dominated the news agenda, Mexico’s drug wars claimed 23,000 lives during 2016 — second only to Syria, where 50,000 people died as a result of the civil war.“This is all the more surprising, considering that the conflict deaths [in Mexico] are nearly all attributable to small arms,” said John Chipman, chief executive and director-general of the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), which issued its annual survey of armed conflict on Tuesday.“The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan claimed 17,000 and 16,000 lives respectively in 2016, although in lethality they were surpassed by conflicts in Mexico and Central America, which have received much less attention from the media and the international community,” said Anastasia Voronkova, the editor of the survey.In comparison, there were 17,000 conflict deaths in Mexico in 2015 and 15,000 in 2014 according to the IISS.Rising death toll

Voronkova said the number of homicides rose in 22 of Mexico’s 32 states during 2016 and the rivalries between cartels increased in violence.“It is noteworthy that the largest rises in fatalities were registered in states that were key battlegrounds for control between competing, increasingly fragmented cartels,” she said.“The violence grew worse as the cartels expanded the territorial reach of their campaigns, seeking to ‘cleanse’ areas of rivals in their efforts to secure a monopoly on drug-trafficking routes and other criminal assets.”Mexican drug cartels take in between $19 billion and $29 billion annually from US drug sales, according to the Department of Homeland Security.Rivalries between the cartels wreak havoc on the lives of civilians who have nothing to do with narcotics. Bystanders, people who refused to join cartels, migrants, journalists and government officials have all been killed.Not on news agenda

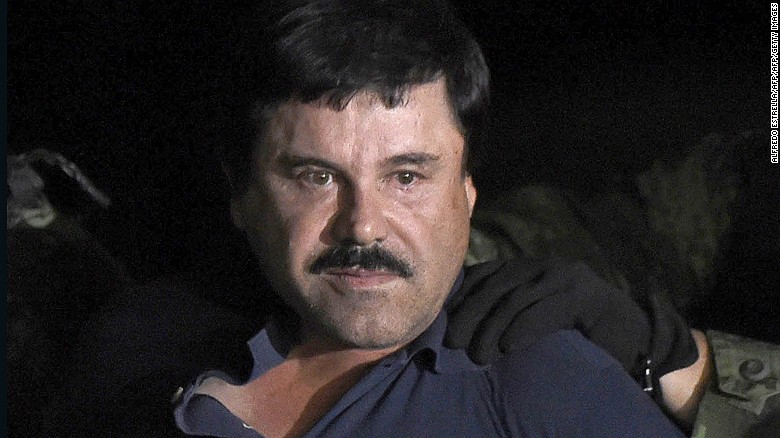

Jacob Parakilas, assistant head of the US and the Americas Programme at London-based think tank Chatham House, said part of the reason for the relative lack of attention paid to Mexico in the international media is “it’s not a war in the political sense of the word. The participants largely don’t have a political objective. They’re not trying to create a breakaway state. It doesn’t come with the same visuals. There are no air strikes.“Also this has been going on since the beginning of the modern drug trade in the Americas. It’s not news in that sense. And Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a journalist. They are intentionally targeted in Mexico, which puts a dampener on the ability to report on this.”There have, however, been significant arrests in relation to the Mexican drug trade in recent times.Damaso Lopez Nunez, a high-ranking leader of Mexico’s Sinaloa drug cartel, was arrested on May 2 in Mexico City and could face charges in the US, authorities said.His arrest follows January’s extradition of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, who is accused of running the Sinaloa cartel — one of the world’s largest drug-trafficking organizations.He awaits trial in New York on 17 counts accusing him of running a criminal enterprise responsible for importing and distributing massive amounts of narcotics and conspiring to murder rivals.World conflict deaths fall

The number of conflict fatalities globally edged down last year, from 167,000 to 157,000, according to the IISS.This was the second successive annual drop — 180,000 people were killed in 2014.The number of deaths in Syria fell from 55,000 in 2015. But there were 1,000 more deaths in Afghanistan last year than 2015 and 4,000 more in Iraq.Voronkova from the IISS said: “Civilians caught amid conflict arguably suffered more than in the preceding years. Between January and August, 900,000 people were internally displaced in Syria alone.”The internal displacement figures were 234,000 for Iraq and 260,000 for Afghanistan.