FBI, Chicago Police Department Work to Combat Violent Crime

Tuesday, April 18, 8:15 a.m.: Along the 5100 block of Halsted Street on the South Side of Chicago, a quiet spring morning is interrupted by gunfire. Police respond to a gas station and discover a drive-by double homicide. As they secure the crime scene and work to identify the bodies and recover evidence, distraught family members of the victims begin to arrive, their faces full of anguish and disbelief. They will not be alone in their grief. By the end of the day in a city reeling from violent crime, there will be 13 more shootings and another murder.

Chicago’s extreme gun violence—762 homicides last year and more than 4,000 people wounded—has been described as an epidemic. Primarily gang-related, the shootings are often spontaneous and unpredictable, and the toll on victims, families, and entire communities cannot be overstated. That’s why the FBI’s Chicago Division, working with the Chicago Police Department (CPD) and other agencies, has undertaken significant measures to address the problem.

***

“The FBI sometimes battles a perception that we are only interested in terrorism or public corruption or large drug-trafficking organizations,” said Michael Anderson, special agent in charge of the Chicago Division. “The fact is, we are interested in those things, but in Chicago we are also getting down to the street level to address violent crime, and we are specifically going after the trigger-pullers and shot-callers.”

That street-level focus is in response to a city homicide rate that has “increased exponentially,” Anderson said. “The number of shootings is at a level that hasn’t been seen here since the early 1990s.” As a result, he explained, “what you are seeing and will continue to see in Chicago is a sustained FBI effort to support and supplement our local partners.”

That effort involves three major areas:

- The creation in 2016 of a homicide task force—in addition to the FBI’s existing violent crimes squad—in which agents work alongside CPD detectives and other law enforcement officers to assist in solving the city’s murder cases;

- Increased intelligence-gathering efforts to identify shooters and “directors of violence,” which includes embedding FBI analysts at CPD headquarters; and

- Stepping up community outreach efforts to gain the public’s trust and enlist their help in solving crimes and making communities safer.

At Chicago Police Department headquarters, personnel in the Crime Prevention and Information Center monitor violent crimes throughout the city using surveillance video and other sophisticated tools. FBI analysts assigned to the center offer additional real-time intelligence that helps police officials deploy resources as efficiently as possible.

“Simply put,” said CPD Superintendent Eddie Johnson, “the FBI has more resources than we do. We combine the resources we have with the ones they have to fight these crimes.”

FBI and CPD personnel working together in the city’s most violent neighborhoods “has helped quite a bit,” Johnson said. “And we get real-time intelligence from the FBI that we didn’t get before. They can look at our crime picture and help us figure out where to best deploy our resources.”

Johnson, a Chicago native and 29-year veteran of the police force who spent many years as a patrol officer, believes a key reason for the city’s current violence is inadequate gun laws.

“The flow of guns into Chicago is just insane,” he said. “You will find that gang members would rather be caught with a gun by law enforcement than caught without one by their rivals. What we have to do through legislation is create a mentality where gang members won’t want to pick up a gun,” he explained. “You create that by holding them accountable for their actions. We simply don’t do a good job of that right now.”

Johnson recalled that when he joined CPD in 1988, he and fellow officers responded daily to calls of gang fights in progress. “We rarely hear that call anymore,” he said. “What we hear now is a person with a gun or a person shot. They just go straight to a firearm and they resolve their disputes with a weapon.”

“What you are seeing and will continue to see in Chicago is a sustained FBI effort to support and supplement our local partners.”

Michael Anderson, special agent in charge, FBI Chicago

“Communities are being hijacked by a relatively small percentage of people,” Anderson said. “The overwhelming majority of residents are hard-working citizens going to work, going to school, trying to go about their daily lives. These communities are under siege, and they are desperately looking for help.”

Of Chicago’s 22 police districts, the majority of violent crimes are taking places in a cluster of neighborhoods on the South and West Sides. “A handful of districts—probably five or six—are responsible for the disproportionate number of homicides and shootings,” Anderson said.

FBI and CPD investigators have focused considerable effort on two of the city’s most historically violent areas—the 11th District on the West Side and the 7th District on the South Side. “Since we put the task force in place,” Johnson said, “we’ve seen significant drops in gun violence in these two districts. We are making some real positive gains,” he said. “By no means are we declaring success, but we have seen some really encouraging results.”

Driving through the city’s most violent neighborhoods—Austin, Englewood, North Lawndale, Auburn Gresham—the streets and parks appear peaceful, and often they are. But when the violence comes, it is sudden and usually without warning. One gang member might have disrespected a rival gang member—increasingly through social media (see sidebar)—and they go looking for each other to settle matters with their guns.

“When I started as a cop,” Johnson said, “if you had a gang of 10 guys, maybe two of them at most would be armed. Now if you have a gang of 10 guys, probably nine of them are armed. And we’ve seen kids as young as 10 and 11 with firearms.”

Investigators agree that gang members are arming themselves at younger ages. “Based on what I’ve seen over the last year,” one FBI agent said, “these guys are carrying around guns as if it’s a symbol of their pride or who they are—and the bigger the gun, the better. We are seeing handguns with extended magazines and ammunition drums attached. It’s like guns are a part of them, a part of their culture. And they are not afraid to use them.”

“We get real-time intelligence from the FBI that we didn’t get before. They can look at our crime picture and help us figure out where to best deploy our resources.”

Eddie Johnson, superintendent, Chicago Police Department

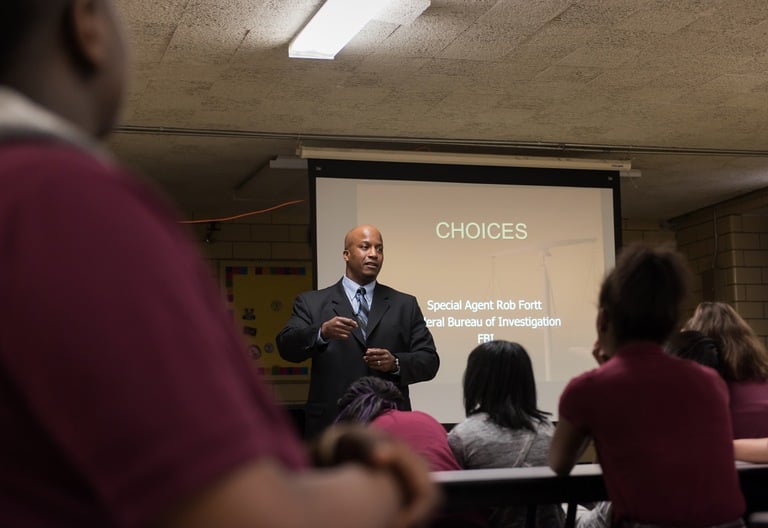

In addition to working closely with the Chicago Police Department to stop gun violence, the FBI has a strong community outreach program. At the Plato Learning Academy middle school in the Austin community, Special Agent Rob Fortt speaks to students about the dangers of joining gangs.

The FBI is working to reach some of these youngsters before they get involved with gangs—it’s one part of the Bureau’s larger community outreach effort in the campaign to stop gun violence. At the Plato Learning Academy middle school in the Austin community recently, Special Agent Rob Fortt spoke to sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-graders about the choices they make and the consequences of those choices.

The school’s principal, Charles Williams, welcomed the opportunity for the FBI to give students a fresh perspective on law enforcement and a positive message about making good decisions. Describing the neighborhood’s reputation for violence, Williams said he has heard gunshots in the middle of the day from his office, and violent crime is a fact of life. “Our students are surrounded by it, unfortunately. It’s just something that permeates the neighborhood.”

Gang-related homicides in Chicago are most easily solved when witnesses come forward. But in the city’s violent neighborhoods, many who witness shootings or have information don’t cooperate with law enforcement, either because they distrust the police or they want to engage in “frontier justice” and seek their own retaliation, the FBI’s Anderson said. “So we are putting a lot of resources into community outreach. We are really focusing on going out in the community and building trust. If folks trust law enforcement, they are more likely to report crimes.”

***

“We have to acknowledge that we have a fractured relationship with the community,” the CPD superintendent said. “But we’re working hard to rebuild that, and the FBI is helping us do that.” Johnson added, “I haven’t been to a community meeting yet where people have said they want less police. What they want is the police to be fair, respectful, and to get the bad guys out of their communities. That’s what they want. And you start that by having a constant dialogue with them, which we are doing.”

Community activist Andrew Holmes represents another important part of law enforcement’s outreach efforts. Holmes, who has experienced the tragedy of gun violence firsthand, has been working with the FBI since 2013 on issues involving gun crimes and the human trafficking of children. He is known to law enforcement and residents of violent neighborhoods as a rapid responder when a homicide occurs. He arrives on the streets at all hours of the day and night to counsel and comfort the families of victims. And he encourages witnesses to come forward.

The work is meaningful to Holmes because his daughter was killed in Indiana when she was innocently caught in the crossfire of a gang shooting. And he recently lost an 11-year-old cousin in Chicago who was killed by a stray bullet meant for a gang member. Holmes also visits high-crime neighborhoods, going street to street to hand out pamphlets urging residents to report gun crimes. In the troubled Auburn Gresham community recently, he spoke to Betty Swanson, block captain of her neighborhood watch group.

Community activist Andrew Holmes has been working with the FBI since 2013 on issues involving gun violence. He regularly visits high-crime neighborhoods to urge residents to cooperate with law enforcement. In the Auburn Gresham community recently, he spoke to Betty Swanson, block captain of her neighborhood watch group.

On the porch of her tree-lined street, Swanson told Holmes that one of her grandsons had been murdered a few months ago. “He was going to visit his mom … after he got off work. Somebody walked up to the car and shot him. He was 28 years old.”

Although her street is largely violence-free now because so many of the residents are senior citizens, Swanson said her block group works hard to keep the area safe, and—like Holmes advocates—that means speaking up when necessary.

“One thing we try to do is to let witnesses know that it’s okay to talk,” Holmes said. “We ask people to engage with law enforcement. You’ve got to work with law enforcement. I don’t care who it is—FBI, state police, U.S. Marshals, Chicago Police—you have to.” Otherwise, the help needed to save a loved one might come too late. “You’ve got to reach over and get that phone, call the FBI,” he said. “Show these criminals—not this block, it’s not happening.”

Murder and Social Media

For those unfamiliar with Chicago’s rampant gun violence, it would be easy to think that shootings happen because of traditional turf battles—one gang trying to muscle in on a rival’s street-corner drug business. But that reality occurred in a time before social media. The new reality is increasingly virtual, and social media is playing a prominent role in the murder rate.

Violence can indeed result from “gang-on-gang and some narcotics territory disputes,” said Chicago Police Department Superintendent Eddie Johnson, “but a lot of our gun violence now is precipitated by social media.”

One gang member disrespects a rival on social media, and the rival responds in kind. The virtual argument escalates, and the gang members look to settle things with weapons. Using their electronic devices, gang members can often pinpoint their rivals’ location.

“Gun in one hand, smartphone in the other,” said Special Agent in Charge of the FBI’s Chicago Division Michael Anderson. Too often, that makes for a deadly mix. And in many cases, the time between the online dispute and actual shots being fired, Anderson said, “is very short.”