The Forgotten Holocaust: The Films of Boris Maftsir

An Israeli filmmaker works to revive the neglected, terrible history of Shoah victims in the Soviet Union

Tablet: In a series of spellbinding documentaries, Boris Maftsir, an Israeli filmmaker, has been racing to prevent the last traces of the Holocaust in the USSR from vanishing for good. He went deep into the forests of Belarus to film the remnants of Tuvie Bielski’s partisans’ camp and document instances of Jewish resistance that have not been widely known until now. While it is hard to imagine anything remains to be said about the Shoah, that, says Maftsir, is because we keep retelling half the story—the story of the destruction of the Western European Jewry, from ghettos to gas chambers and everything those stand for: the merciless, mechanized, industrial-scale killing machine that organized the murder of millions into a precise, assembly-line-like operation.

While half of all the Shoah victims died in the Soviet Union, they died very different deaths. Here, people died in mass executions in ravines, forests, and village streets, at the hands of Germans or local collaborators. They perished right where they lived, in front of people who had been their neighbors.

Because the Nazis put Soviet Jews, whom they called Judeo-Bolsheviks, in a separate category and viewed them as particularly dangerous (and because they expected a quick victory here) with a few notable exceptions, they almost never bothered with organizing the Jews into long-term ghettos or transporting them to faraway places. Jews began dying the moment Germans invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

“By the end of 1941,” writes Timothy Snyder in Holocaust: The Ignored Reality, “the Germans (along with local auxiliaries and Romanian troops) had killed a million Jews in the Soviet Union and the Baltics. That is the equivalent of the total number of Jews killed at Auschwitz during the entire war. By the end of 1942, the Germans (again, with a great deal of local assistance) had shot another 700,000 Jews, and the Soviet Jewish populations under their control had ceased to exist. … By 1943 and 1944, when most of the killing of West European Jews took place, the Holocaust was in considerable measure complete.”

A different set of numbers throws this into even sharper relief. An estimated 25 to 27 percent of Amsterdam Jews who found themselves under occupation survived—the lowest rate in Western Europe. In France, 75 percent of Jews survived the Nazi occupation. By contrast, of the conservatively estimated 2.61 to 2.75 million Soviet Jews who found themselves living under Nazi occupation, an estimated 103,000 to 119,000 survived, for a survival rate of between 2.7 percent and 4 percent. (Estimates of victims include only those who died as a result of direct anti-Jewish actions by the Nazis; they do not include hundreds of thousands of Jews who fell in battle while serving in the Red Army or died during sieges of Leningrad and Odessa from bombings, hunger, illness, and other causes. These are estimated to constitute several hundred thousand.)

Maftsir doesn’t mince words when he talks about the near-erasure of the eastern half of the Holocaust. “The place of memory of the Holocaust is already taken up,” he says. “There is the Victim—Anne Frank. There is the Saint—Janusz Korczak. There is the Villain—Adolf Eichman. There is Hell, it’s Auschwitz. There is heroism—the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. And that’s it.”

***

I met Maftsir in September 2016 in Kyiv, where I was attending a series of events commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Babi Yar massacre. At one of the events, Maftsir showed the first film of his Holocaust in the USSR project, Guardians of Remembrance. It was the first time in my life that I, who grew up in the Soviet Union, saw people I could recognize and relate to—survivors from Belarus, Russia, Ukraine—speaking to me from the screen, in Russian, about the horrors of the Holocaust. They told the story of a Holocaust that happened in places where my family had lived.

Maftsir has been working on his project since 2013, but its roots go back to his time at Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, where for seven years he headed up the effort to recover the names of the Soviet victims of the Shoah. When he took the job in 2006, he was shocked to discover how many were still missing.

“I knew that in Soviet times, for ideological and political reasons, there was neither documentation, nor memorialization, nor the study of the Holocaust,” he told me. “But I couldn’t imagine that out of the 1.5 million Jews we believe died in Ukraine, we had only 10 to 15 percent of the names.” This figure stood in contrast to the names of Western European Jews who died in the Holocaust, 90 percent of which were known at the time.

Maftsir spent the next several years traveling to some 160 Shoah sites in the former Soviet Union, a mind-boggling number that is nevertheless only a fraction of the total of 2,000 sites connected to the Holocaust. Today, these sites are spread out across several post-Soviet states. Step by step, he built a network of local volunteers who sought out Holocaust survivors, non-Jewish witnesses, and local memory activists—the so-called guardians of remembrance. “We did not work with archives,” Maftsir emphasized. “We were looking for living memory.”

His team collected hundreds of thousands of names. And at the end of his seventh year on the project, Maftsir realized that he needed to bring this story before a larger audience. As a professional filmmaker, he chose film as his medium. In 2012 he resigned from the project at Yad Vashem to make Guardians of Remembrance.

“What does it mean to shoot almost everyone or to destroy nearly 3 million people across a span of a given territory?” asks Maftsir. The question is only partly rhetorical. In the USSR, it meant there were virtually no survivors left to tell their stories. Those who had managed to evacuate before the German invasion or who had served in the Red Army came back to find empty homes and mass graves. Their grief was suppressed under the blanket Soviet policy of silence and denial of the specificity of the Jewish nature of the Holocaust.

The Soviets, of course, knew exactly what had happened to the Jews in their territory. Even before the war ended, a special state commission began investigating German crimes, including those against the Jews. A group of Soviet Jewish writers began collecting witness testimony and preparing it for publication in a work that became known as the Black Book of Soviet Jewry. Some of these materials became evidence in the Nuremberg trials.

But the findings of the commission were never published in the USSR. Many of those who worked on the Black Book were executed a few years later, charged with disloyalty, as the campaign against “rootless cosmopolitanism” unfolded. It would have been ideologically uncomfortable for Stalin to emphasize Jews as a particular target, for doing so could have detracted from the special status of the USSR as a whole as a target of Hitler’s aggression. It could also have given credence to Hitler’s propaganda about the Judeo-Commune and reinflamed anti-Semitic tendencies among the local populations that needed to be reintegrated—and reindoctrinated—after prolonged periods of living under the German occupation.

In the vast majority of cases, there were no monuments or other works commemorating the execution sites. In the few cases with some sort of memorial, the inscriptions referred to the victims as “peaceful Soviet citizens.” Relatives were not permitted to gather at the memorial sites. Those who did were often arrested. Western scholars were denied access to the archives to conduct research.

“What do deniers of the Holocaust say?” asks Maftsir. “They say: Look at the USSR. Show us the corpses. But everything there is burned down, everything is ground down, everything is destroyed. The forgetting by the Soviet power for 40-50 years has led to the fact that there is no direct connection anymore. And that is how memory goes away.”

***

As Dr. Inna Gerasimova, the founder of the Museum of Jewish History and Culture of Belarus, tells her story in one of the opening scenes of Guardians of Remembrance, the camera pans across a square garden in the center of Minsk, where she and Maftsir are discussing the events of November 1941.

“This is where the gallows stood,” she tells him, motioning with her hand. Around them is a street scene that is unremarkable in its normalcy. Passers-by are going about their business, some with the habitual urgency of a city-dweller, some just strolling. Most are oblivious to the cameras. It’s a gray, rainy afternoon in late November, and pedestrians are studiously avoiding the puddles. You can almost feel the chill in the air.

“It is precisely here that once in a while they hanged people,” Gerasimova continues, and the growing dissonance between her words and the humdrum, quotidian reality on the screen sets off a barely detectable alarm bell of internal discomfort in the viewer.

“The people began to panic from the very beginning. They felt frightened because right away they realized the most scary thing—the complete permissiveness that was indulged in by those who kept them here. They raped women, they raped girls, and they did it openly.” As she speaks, the camera cuts over to a well-dressed young woman with two school-age sons. The boys look back at the camera, giggling the way preteen boys anywhere might do. Gerasimova’s narrative of the horror that took place in these very streets clashes with the visual of the weirdly normal, peaceful scene playing out on-screen.

And suddenly it hits you. It was people just like these—regular, ordinary residents whom any one of us could identify with—who became swept up in the horrible events she is describing. Suddenly you can visualize and feel in your gut the shock and horror of seeing the gallows erected in the heart of your city. It could have been anyone who happened to be a Jew. It could have been you.

It is Maftsir’s ability to create this presence that makes his films so powerful. To achieve this, he films on location, at the same time of year when the events his informants describe took place. This means that he’s had to film in 1 degree F in Sukhari in Belarus, 104 degrees F in Zmievskaya Balka in the south of Russia, and in the pouring rain in Minsk. His films are based entirely on witness and survivor testimony, and he takes his witnesses to the places where they experienced the events. He asks them to tell their stories in the language they spoke in their childhood, whether it be Russian, Yiddish, Ukrainian, or Romanian.

This produces a lot of difficulties. “Physically, it’s very hard,” he told me. “You come to Berezhany in Western Ukraine with a witness. He is over 80, he is afraid of getting sick. And the rain starts, and he thinks, naturally—what will happen to me? And you have to work with people so they don’t cry, so they can tell the story.”

And they do tell their stories. They tell their stories all over the Holocaust country of the former Soviet Union, from Nalchik to Khatyn to Lubavichi, the birthplace of Chabad. The relentless narrative of Maftsir’s films, in which each episode of annihilation unfolds chronologically as one story builds on another, paints a picture of what he refers to as “the organized chaos” of the Holocaust in the USSR. In many ways, it can be said that it was here that the Nazis invented, practiced, and perfected techniques of mass executions; learned to manipulate and control crowds of future victims to prevent panic from setting in too early; learned what incentives worked to supply them with streams of local collaborators. It was out of the chaos of these early months of the Holocaust that the well-oiled extermination machine of later years arose.

To be sure, Germans had their orders to annihilate Soviet Jews, but, in Maftsir’s view, there wasn’t an organized plan.

“Take the example of the Romanians,” he says. “Why is it that in Zhmerinka you have an ‘exemplary’ ghetto, and in Bershad hundreds are dying each day? That one is run by Romanians and this one is run by Romanians. In Bogdanovka there are executions taking place locally, but in the northern part of Vinnytsa region people are basically told to live or die any way they wish.”

This lack of organization and preplanning, in his view and that of many historians, extended even to such massive events as Babi Yar.

“Babi Yar was a horrible tragedy,” says Maftsir. “But it wasn’t the first. And it wasn’t even unique in its scale.” He rattles off several notorious mass execution sites. Kamenets-Podolsk: two days, 23,600 people, a full month before Babi Yar. The Rumbula massacre in Riga: 25,000 Jews over two nonconsecutive days in late November and early December 1941. By then, he says, “they already knew how to do it.”

***

So far, Maftsir has completed four of the nine films he has planned. All four—Guardians of Remembrance, Holocaust: The Eastern Front, Beyond the Nistru (parts 1-3 and 4-5), and Until the Last Step—are available online. Of particular interest in Until the Last Step, which is shot in Belarus, are stories of little-known instances of Jewish resistance.

How reliable are the accounts he presents? Witness testimony is a contentious issue among historians. One problem is that people’s memories can be unreliable, especially many decades later. Bystander testimony can be particularly problematic, Dr. Kathleen Smith, a professor at Georgetown University focusing on issues of memory and historical politics, told me: “Bystanders are people who perhaps weren’t specifically targets of repression. They were there, and one might ask, well, what were you doing? Were you a collaborator or were you just someone who was scared? Were you someone who tried to help the victims? It’s much more messy when you try to pull information out of people who were bystanders.” In fact, it is well known that neighbors often benefited from the Jews’ misfortune.

When I put these questions to Maftsir, he is careful to emphasize that his witnesses were children or teenagers when the events took place. “Each of them talks about what they saw. And they do it sometimes very honestly,” he says. “It was a terrible time. It was occupation. I don’t know how people lived and how they survived. Even the righteous who saved people did not do it for free: they had to get food for the people. Those who saved themselves had to pay for it.”

Not a single historian who has viewed his films has ever raised objections about the veracity of testimonies, says Maftsir. “I don’t make things up and I don’t uncover anything new,” he stresses. “All the events that are described are well documented. I simply recreate these events. Each witness talks only about what she saw.”

In fact, a number of organizations in Israel use his films in their Holocaust education programs, including the Ghetto Fighters’ House museum.

“To what extent are these testimonies history? I don’t know,” he says. “It’s memory. And my entire project is about the restoration of memory about the Holocaust in the USSR. I collect imagery to convey the scale, the prevalence, the uniqueness, the systematic nature of what happened through personal stories.”

In a strange way, Maftsir’s films give one a sense of hope. After all, these are the stories of survival and resurrection of memory; stories that defied the intended triple annihilation of death, burial in mass graves, and forgetting.

One of the most emblematic scenes in the film is one of a Soviet World War II veteran, Emil Ziegel, who now lives in Israel, coming back to Mineralny Vody, Russia, with his Israeli grandson to show him where he came from and tell him the story of losing his family in the Shoah. “By the time you have children, I probably won’t be alive,” he says to him. “You bring them here, tell them what I told you today.”

***

To read J. Hoberman’s Tablet magazine review of a series of Holocaust movies made in Communist countries, click here.

A draft executive order circulating on social media Wednesday indicates the U.S. military could be used to establish and secure refugee camps in Syria. (Via Twitter)

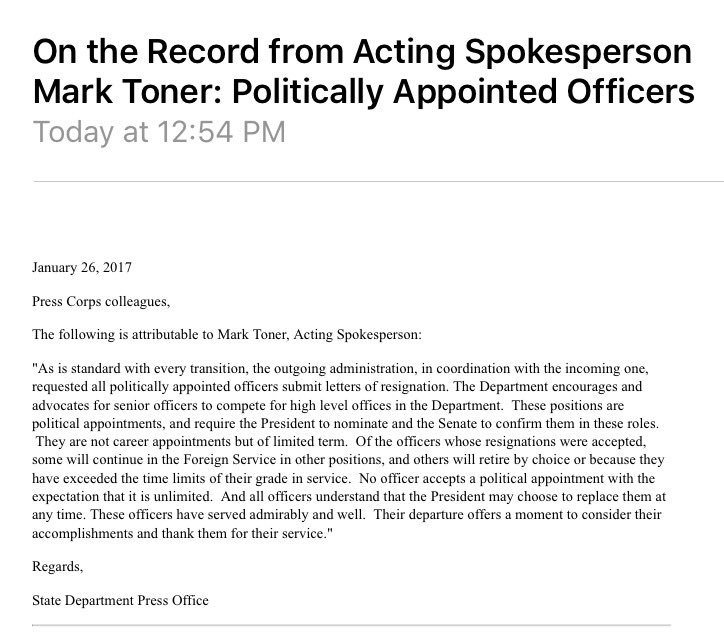

A draft executive order circulating on social media Wednesday indicates the U.S. military could be used to establish and secure refugee camps in Syria. (Via Twitter) Rex Tillerson was there at Foggy Bottom getting a lay of the landscape, when the resignations turned in last week became effective today as there was a walk out. And YES, the most corrupt official at the State Department remaining after John Kerry left is

Rex Tillerson was there at Foggy Bottom getting a lay of the landscape, when the resignations turned in last week became effective today as there was a walk out. And YES, the most corrupt official at the State Department remaining after John Kerry left is