Part one of this investigation, go here.

Additional information regarding the requirements by TSA, go here.

Could 9/11 happen again? The answer is yes but it would not follow the same model as that fateful day. Follow this narrative to see the gaps.

Then, the new director of the FBI gave some compelling testimony this week about the drone threat.

The FAA was warned in 2009 that people with terrorist ties were licensed to fly and repair aircraft. Eight years later, it is, incredibly, still the case.

Nader Ali Sabouri Haghighi’s own pilot certificate, it turned out, had been revoked years earlier for providing false information, but the Federal Aviation Administration conveniently mailed him a new one. Haghighi had called the FAA hot line claiming to be a professional pilot named Daniel George who had lost his license. He then recited George’s license number and other personal details that he’d obtained from their business dealings. Without asking further questions, the FAA agent sent Haghighi a license with George’s name on it.

It ought to have been difficult for the black-haired, brown-eyed Iranian to use a pilot’s license belonging to a fair-skinned, gray-haired American nearly 20 years his senior, except for one factor: FAA pilot licenses do not include photographs of the pilot. Haghighi was able to pull off his ruse for nearly four years until Danish police found the license in the rubble of the crash.

Almost a decade after Haghighi’s brazen identify theft, the FAA still does not include pilot photos on its licenses, and the agency does not fully vet pilot information before issuing them credentials. Last year, a leading congressional overseer of the FAA, then-Representative John Mica, called US pilot licenses “a joke” and said that a day pass to Disney World in his native Florida contains more sophisticated security measures.

FAA officials defend their licensing practices, noting that pilots are also required to carry a government-issued ID such as a driver’s license to prove their identity. The pilot certificate, they say, is more an indicator of the pilot’s level of training than a security tool, and commercial airports and airlines generally issue their own IDs for access to tarmacs, planes, and other secure areas.

But the flawed airman licenses are part of a troubling pattern of lax oversight of more than 1 million FAA-approved airmen — including pilots, mechanics, flight attendants, and other aviation personnel — that has made the agency vulnerable to fraud, and the public vulnerable to those who mean to do harm, a Spotlight Team review has found.

After the 9/11 attacks, Congress called on the FAA to overhaul its licensing for more than 600,000 US-certified pilots. But the FAA’s changes so far have been modest, such as making licenses with higher-quality materials to reduce forgeries. Today, FAA security procedures remain geared more toward the convenience of pilots than the needs of a nation engaged in a “war on terror,” often failing to challenge airmen’s claims on their applications and seemingly unaware of deceptions.

Haghighi, for example, continued to finagle help from the FAA even after he went to jail in Denmark for flying without a valid license and endangering his passenger. After his release, the FAA issued him a medical certificate that helped him land a job at an airline in Indonesia in 2014. All he had to do was change one letter in the spelling of Sabouri and alter his birth year. An official at another federal agency eventually tipped off the FAA to Haghighi’s duplicity.

Or take the case of Richard Hoagland. Beginning in 1994, he purchased homes, registered a plane, obtained a pilot license, and even got married under the name Terry Symansky, according to court records. The ruse wasn’t discovered until Symansky’s nephew was doing family research on Ancestry.com and found that his late uncle was listed as alive. The FAA never caught on that the real Terry Symansky had been dead since 1991, issuing Hoagland a new private pilot certificate in Symansky’s name as recently as 2010. Hoagland is now serving a two-year sentence in federal prison for identity theft.

FAA procedures also make it easy for pilots to hide damaging information, by simply not reporting it. That’s because the agency relies on them to self-report felony convictions and other crimes that could lead to license revocation. Among the licensed pilots currently listed in the airman registry are Carlos Licona and Paul Grebenc, United Airlines pilots who were sentenced to jail in Scotland earlier this year for attempting to fly a commercial airliner with alcohol in their blood. Under FAA rules, an alcohol-related offense, especially related to flying, can be grounds for license revocation or suspension, though the FAA decides on a case by case basis.

But as of Sept. 1, Grebenc and Licona were still listed in the FAA’s active airman registry. Agency records showed that as of January, four months after the men were arrested, there were no reported incidents or enforcement actions related to the pilots.

FAA officials stress that they are not the police officers of the skies, leaving that job to an alphabet soup of agencies including the Transportation Security Administration, Homeland Security, and the FBI. The FAA merely issues the airman certificates and keeps the database that helps these investigators do their work. And, while FAA officials admit they don’t routinely investigate information that pilots, mechanics, and others list on license applications, the TSA says it continuously reviews the FAA database against the Terrorist Screening Database, additional terrorism-related information, and other government watch lists. Since 2010, the TSA has completed 28 million airman threat assessments.

But it is hardly a fail-safe system. Outside reviewers have repeatedly found that the FAA’s Airman Registry is riddled with errors and gaps, making it difficult for law enforcement officials to rely on. More than 43,000 pilots received licenses even though they did not provide the FAA with a permanent address, according to a 2013 audit by the Department of Transportation inspector general. Two years earlier, the Department of Homeland Security inspector general found that 8,000 of the Social Security numbers on file belonged to dead people, in part because the FAA doesn’t purge its files of dated information. Another 15,000 didn’t match the airmen’s personal information on file.

When asked whether the FAA vets the information on airman certificate applications, officials did not answer directly. The FAA issued a statement reading, “Pilots are expected to provide accurate and complete information on all FAA forms.”

Agency officials also said that, when pilots apply for medical certificates — a crucial document needed to fly — they conduct a one-time check against the national drivers’ database for drug- or alcohol-related convictions.

The lack of accurate information can have serious consequences. Last October, when a student pilot from Jordan intentionally crashed a twin-engine plane near a major defense contractor in East Hartford, Conn., law enforcement officials initially feared terrorism and converged on the Illinois address he had given the FAA. But the student, Feras M. Freitekh, had listed the address of a family friend, a place where he had never lived, so law enforcement descended on a house nearly 900 miles from his actual home.

Most worrisome, even with ongoing TSA vetting, people with suspected or proven ties to terrorism still keep active airman certificates.

FAA-Approved offenders

Mark Schiffer couldn’t believe what he was finding.

Schiffer, the chief scientist for a company that helps banks detect fraud, was simply testing an algorithm to check names against publicly available watch lists that included suspected terrorists and other bad actors. In April 2009, he was using data from the FAA Airman Registry for his test because the list was large and readily available.

But he kept turning up terrorists.

There was Fawzi Mustapha Assi, who was on the FBI’s most-wanted list for five years before being convicted of providing material support to Hezbollah in 2008. Though imprisoned, he had an active pilot’s license, which never expires. His release was expected in a few years.

Also on the list was Myron Tereshchuk, an FAA-certified mechanic and student pilot, who was convicted in federal court in 2005 for possession of biological agents or toxins that could be used as weapons. Tereshchuk was also in prison, but he, too, was expected to be released in a few years.

And there was Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi, who was sentenced to life in prison for his role in the bombing of Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland. Scottish authorities released him in 2009 on compassionate grounds after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He still had a valid aircraft dispatcher certificate from the FAA.

“Holy cow,” Schiffer said to himself.

In all, Schiffer and his company, Safe Banking Systems of New York, confirmed eight matches between FAA-approved airmen and various watch lists.

“The results were as unexpected as they are chilling,” Safe Banking Systems said in a June 2009 report distributed to nearly 40 lawmakers and top government officials, including the FAA administrator and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

But no one responded until a New York Times reporter asked the Transportation Security Administration about the certified airmen with terror ties listed in the Safe Banking Systems report. The following day, in June 2009, the TSA advised the FAA to revoke airman certificates for six of the eight names that SBS gave to the reporter.

The Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general, in an 18-month investigation released in July 2011, found that the TSA’s ability to screen airmen for national security threats is hampered by the quality of information the FAA provides. The TSA could not properly vet thousands of airmen because of missing or inaccurate data within the FAA’s registry, according to the report. From 2007 to 2010, the TSA recommended the revocation of 27 licenses, but that number would likely have been larger had all of the information been complete.

The inspector general also found that the TSA doesn’t screen for broader criminal activity, allowing airmen who “have outstanding warrants or are known fugitives” to escape detection. The IG said that one US-approved pilot was actually a “drug kingpin” serving 20 years in a foreign prison.

Since then, the TSA and FAA have stepped up their screening for national security threats, reviewing the FAA database four times a year to ensure accuracy.

The Spotlight Team wanted to check whether the heightened scrutiny has improved the FAA’s record in preventing bad actors from having pilot’s licenses. At the request of the Globe, Safe Banking Systems tested the public part of the airman registry and again found problems.

Running the same name-matching program in January 2017, SBS found five active airmen on watch lists with possible ties to terrorism or international crime, including Tairod Nathan Webster Pugh, a former Air Force mechanic who bought a one-way ticket to Turkey in 2015. His packed bags included flash drives with maps, a letter to his wife about jihad, and his Federal Aviation Administration airman certificate, according to court records. When he was arrested, Pugh was headed to Syria to offer himself as an aircraft mechanic.

In May, Pugh was sentenced to 35 years in prison for attempting to provide material support to the Islamic State, though he is appealing.

On Aug. 1, Pugh’s name still appeared on the FAA’s list of active airmen. But Pugh was removed by Sept. 1, days after the Globe requested his records. FAA officials now say that Pugh’s license was actually revoked in 2015, though on Friday, they could not explain why his name continued to be on the active list for another two years.

In addition, SBS turned up a long-time American Airlines mechanic who attempted to broker a deal that would have moved seven Airbus A300s to Iran, which the United States has identified as a state sponsor of terrorism; a Florida businessman who was planning on illegally shipping navigation systems used for steering planes, ships, and missiles to Turkey; and an Irish pilot sanctioned by the US Office of Foreign Assets Control for his connections to a company and plane that were also sanctioned. The mechanic and Florida businessman both have been released from prison, while the Irish pilot has not been charged with a crime.

In August, when the Globe requested information about the airmen identified by SBS, FAA records contained no indication that any of the five had faced FAA enforcement action.

“Have things really changed? Does the government know who they are dealing with?” said David Schiffer, Safe Banking Systems’ chief executive officer (and Mark Schiffer’s father). “The fact that some are licensed while still incarcerated is unbelievable. We certainly view this as a very serious threat to national security.”

A History of Deceit

Long before the crash in Denmark, Nader Haghighi had spent years duping the FAA. When his name came across the desk of federal investigator Robert Mancuso in late 2008, Haghighi had already racked up a significant criminal record for stealing a plane, had had his pilot’s license revoked, and had even been deported from the United States in 2006, according to federal investigative reports and court records. And the FAA was receiving two new calls per month about Haghighi’s scams.

Mancuso, a special agent for the US Department of Transportation Inspector General’s Computer Crimes Unit, began investigating a report that Haghighi had tried to illegally obtain a pilot’s license online using Daniel George’s name. Mancuso quickly discovered that George was just one more victim of a con man who used at least a dozen aliases and falsely claimed to have a degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a job at Lockheed Martin.

But Haghighi made a mistake when he initially tried to get George’s license. He had collected George’s personal information when he hired the professional pilot to fly a plane for him. But when Haghighi entered the stolen information online to get a copy of George’s license, Haghighi neglected to change the e-mail address on the account, so George received notification about the new license and contacted the FAA. The agency intercepted the certificate before it was sent out.

And Mancuso thought that was the end of it, though he kept investigating Haghighi.

Then, when Haghighi crashed with George’s license in his possession a few years later, Mancuso made a stunning discovery: Haghighi had found yet another way to get a license. He called the FAA directly, posing as George and complaining that he had never received the certificate he had requested weeks earlier. The FAA, without further investigation, mailed out a new copy to Haghighi’s post office box in Texas, something an FAA employee told Mancuso was “not uncommon for our office to do, based on a phone call from the airman.”

“I was shocked,” said Mancuso, who traveled to Denmark to testify against Haghighi. “I assumed that some type of fraud alert would be placed on Mr. George’s record to prohibit this from happening, especially when it was sent to the same bad address.”

The FAA said pilots today can no longer request duplicate certificates by telephone, but they can get them online or by mail.

During his trial in Denmark, Haghighi tried yet another scam, insisting that his real name wasn’t Haghighi or George but the one on another passport recovered from the crashed plane. But the judge didn’t believe him and sentenced Haghighi to 10 months in prison for endangering passengers, including children, flying without a valid license or a required co-pilot on multiple occasions.

Even then, Haghighi was not through tricking the FAA. A year after his release from prison, in February 2014, he contacted the agency to secure another medical certificate, which is needed for pilots to fly.

On his application, he changed his name from “Sabouri” to “Saboori” and his birth year from 1972 to 1973. According to a US Department of Transportation investigative report, Haghighi lied repeatedly on the form, claiming that he had not visited a medical professional in three years, even though emergency responders had found him unconscious inside a crashed plane just two years earlier.

His word was good enough for the FAA, which gave Haghighi a new certificate that he promptly used to land a job with Susi Air, an Indonesian airline.

Flying again

Haghighi is an extreme example, but his case is by no means isolated. At least one other pilot on the FAA registry, Re Tabib, won his license back after he went to prison for attempting to smuggle aircraft parts to Iran and was formally declared a security threat by the TSA.

In 2006, federal officers seized thousands of aircraft parts, some packed in suitcases, and “shopping lists” from the California home of Tabib, an Iranian-born FAA certified pilot. He was arrested on charges of attempting to illegally export parts for F-14 Tomcat jets to Iran.

Tabib, a veteran airman who at one time piloted private flights for the designer Gianni Versace, pleaded guilty and served time in federal prison from July 2007 until January 2009. Yet, according to court records, the FAA issued him an Airline Transport Pilot certificate, the highest-level license for pilots, just three months after his release, allowing him to fly large jets.

Unlike other pilots with a criminal record, Tabib made no attempt to hide his past, alerting the agency about his felony conviction on an application form that calls on candidates to disclose any previous arrests or convictions. But the FAA — which can suspend flying privileges for anyone with an ATP license it judges not of “good moral character” — did not revoke or suspend his license.

As of August, FAA records revealed no incidents or enforcement records connected to Tabib. The agency declined to comment further on Tabib’s case but said it examines possible violations of the “good moral character” standard on a case by case basis. The agency said that a criminal conviction is not automatic grounds for action against an ATP license.

In June 2009, just months after Tabib received his new certificates from the FAA, Safe Banking Systems, the New York fraud detection company, matched Tabib’s name to public watch lists and passed it along with others to The New York Times.

The TSA responded to the story by advising the FAA to revoke Tabib’s certificate. Tabib’s airman certificates gave him “insider access” that, combined with his connections to Iran, could render him a security threat, according to a 2010 decision by an administrative law judge.

Tabib fought the decision for years and finally reached a settlement with the TSA in 2012. His attorney, Robert Schultz, said the law permitting the TSA to revoke airman licenses is unconstitutional because it treats airmen as presumed guilty without proper due process.

“Mr. Tabib was a professional pilot who was denied the right to earn a living for years based on mere suspicion,” Schultz said, referring to the TSA threat assessment. Last year, the FAA issued him new commercial pilot and flight instructor certificates.

This time, Tabib’s name was kept out of the FAA database of active airmen that the public can download to review the full list of pilots and mechanics. As a result, his name did not appear this year when Safe Banking Systems checked for airmen who had been on terror watch lists. More than 350,000 airmen were excluded from the public database at their request.

Recent social media posts show Tabib in front of a King Air C90 turboprop aircraft. A photo from this spring shows him wearing an aviation headset in the cockpit of a plane at the Azadi airport in Iran. His Facebook page says he’s now a flight instructor and pilot at John Wayne Airport in Orange County, Calif. Tabib is flying again.

Con air

Mario Jose Donadi-Gafaro, a US-licensed pilot, died along with six others in a horrific plane crash in Venezuela in 2008 when his plane plummeted into a bustling neighborhood a few minutes after takeoff. He never made a distress call, and questions still remain nine years later about the cause of the accident.

But another mystery is how Donadi-Gafaro, a pilot who also moonlighted as a drug trafficker, kept a US pilot’s license as long as he did.

Donadi-Gafaro’s criminal career began at least a decade before the crash. His initial US felony drug conviction in 1999 for importing cocaine into Miami International Airport should, under FAA rules, have immediately triggered agency scrutiny of his license.

But even after the pilot was convicted a second time — this time in Venezuela — in 2006 for attempting to transport cocaine on an aircraft, the FAA did not revoke Donadi-Gafaro’s license. Instead, the agency gave him a promotion. He applied for and was issued his Air Transport Pilot’s License, the gold standard of US airmen ratings, on July 23, 2007. Almost a decade after the crash in Venezuela that killed him, the FAA still listed Donadi-Gafaro as an “active” pilot, including him in its database as recently as March 2016.

The agency finally deactivated his license in 2016 after the Globe began asking questions about it. The FAA declined to comment on whether Donadi-Gafaro had reported his conviction, saying that information is protected under the Privacy Act.

‘We don’t know who they are’

A frustrated John Mica held up a plastic card as he addressed a 2016 hearing of his House subcommittee on the topic of “securing our skies.” The card, borrowed from then-Representative Tammy Duckworth, a pilot, was an example of a modern FAA certificate.

“An airline pilot has access to the controls, flying the plane,” said Mica, but a US pilot’s license lacks basic security features and includes only a decorative picture. “The only photo on this license are the Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur. Orville and Wilbur, I blew it up here. OK?”

To make his point, the congressman held up an entry pass for Disney World. The card, decorated with Minnie Mouse, has a magnetic strip that is capable of linking identities to fingerprints. This allows Disney to track when cardholders enter or leave the park. The FAA license is primitive by comparison.

“This is Minnie Mouse,” said Mica, referring to the Disney pass. Then, nodding to Duckworth’s certificate in his other hand, he added, “and this is Mickey Mouse.”

Congress long ago called on the FAA to implement significant changes. The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 mandated not only pictures of pilots, but also that pilot licenses include biometric capabilities such as fingerprints or iris scans.

“Fifteen years later, we see a system that has not complied with the laws that we have passed multiple times,” said Mica. “We have pilots that are flying planes. We don’t know who they are.”

The FAA said that it has made some improvements. In 2003, the agency switched from paper licenses to new “security-enhanced airman certificates,” the FAA said. The plastic documents include an FAA seal and, according to the FAA, are resistant to tampering, alteration, and counterfeiting.

But lawmakers have repeatedly challenged the agency on why the FAA has not followed congressional mandates regarding the licenses. Mica, in particular, voiced his concern publicly about the licenses in letters and hearings in 2010, 2011, 2013, and most recently, last year.

In 2017, the former congressman says he’s still concerned about the lack of progress and failure to have a “credible” document.

“We tried to get them to comply, but they never did fully comply,” Mica said. “Any credit card in your wallet has better capability.”

Many pilots and flight instructors opposed the photo IDs, some complaining that it could add to the cost of licensing without improving national security. In written comments to the FAA, pilots said the photo on the license was unnecessary because they are already required to carry other photo IDs — and because airport officials never ask to see pilot certificates anyway.

“Many of our members describe this effort as ‘security theater,’ putting a photograph on a document that authorities never ask for,” said Doug Stewart, chairman of the Society of Aviation and Flight Educators, in a 2011 letter.

“What is most critical in the issuance of an FAA pilot certificate from a security standpoint is the accurate establishment of the pilot’s identity, background descriptors, and qualifications,” wrote Robb Powers, chairman of the national security committee at the Air Line Pilots Association, International. “Presently, FAA does not verify the identity of the person requesting a pilot certificate other than through visual inspection of the individual’s driver’s license or passport.”

As of last month, the agency said it, along with the Department of Transportation, is “still evaluating options for including a photo,” a project expected to cost about $1 billion.

While the FAA has pondered additional security requirements for more than a decade, special interest groups have worked to quietly relax regulation for pilots. In a victory for advocates of general aviation, Congress eased the medical requirements for pilots seeking a basic license, requiring only a visit to the family doctor and participation in an online course provided by the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. And the FAA reauthorization bill now in the Senate includes an amendment to roll back some commercial pilot training requirements enacted after a 2009 regional airline crash that killed 50 and was blamed on pilot error.

‘What a nightmare’

Early into his new job, officials at Susi Air in Indonesia grew suspicious of Nader Haghighi and discovered that his passport number belonged to someone else. They alerted the United States.

Robert Mancuso, the Department of Transportation investigator who tracked Haghighi for years as the con man fooled authorities while using many aliases, including Nader Schruder, learned about the latest escapade and sent an e-mail to FAA officials.

“Hello all! It’s my yearly e-mail regarding Mr. Nader Schruder. He seems to have popped back up in Indonesia with his revoked FAA certificate . . . Can you also run a search for any pilots with the name ‘Nader Ali Saboori’ to make sure he doesn’t have another certificate.”

The FAA responded the next day: “I do show a record for SABOORI; Nader Ali with a First Class Medical certificate issued 2/27/14 . . . It’s probably the same airman.”

Haghighi soon after found himself without a job. He left Indonesia and was detained during a stopover in Panama after US authorities put out an alert. In November 2014, Haghighi pleaded guilty in US District Court in Houston to four counts of identity theft.

George, the man whose identity Haghighi stole, wrote a letter to the judge detailing the personal toll — hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost revenue from potential pilot positions and thousands of hours spent trying to figure out where Haghighi would turn up next.

“What a nightmare this man has been to me personally and professionally,” George wrote.

After Haghighi was released from federal prison in October 2016, he was deported to his native Iran — ending roughly 15 years of deception.

“It’s sad it went on this long. He was putting the public’s life in danger,” said Mancuso, now a special agent at another federal office of the inspector general.

Haghighi, in Facebook messages to a Globe reporter, expressed no remorse for his behavior and described the FAA in bluntly critical terms: “know the right person, pay the right amount in a right way and then the sky turns green.”

The Globe could find no evidence that Haghighi has a US pilot’s license today, but a Facebook photo update in March suggests he hasn’t given up hope: He was smiling from the cockpit of a plane with his hand inches away from the controls.

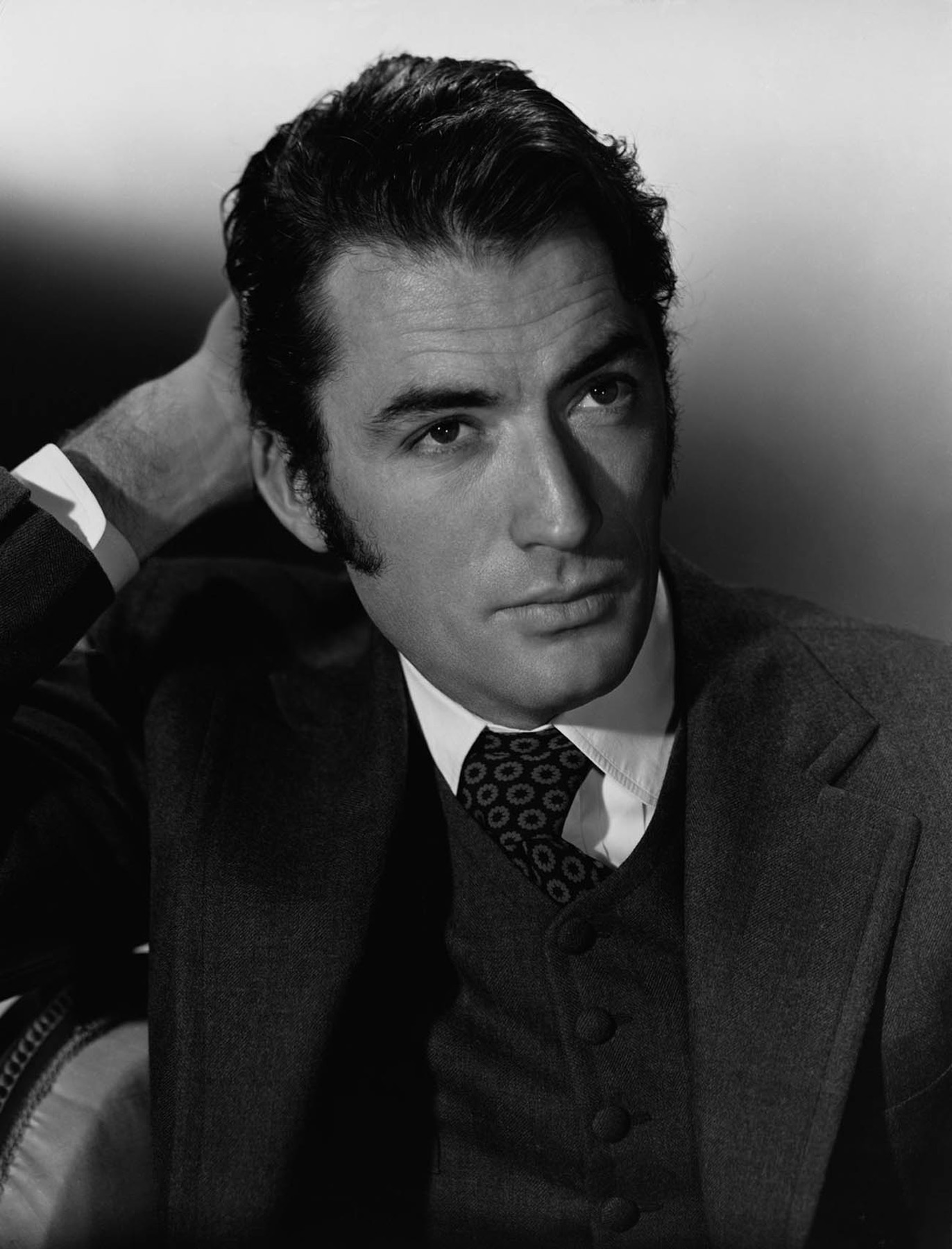

Gregory Peck

Gregory Peck  Joanne Woodward

Joanne Woodward Photo

Photo