The RegisterUK

The RegisterUK

Wired: Ten days after US intelligence agencies pinned the breach of the Democratic National Committee last October on the Russian government, Vice President Joe Biden promised government would “send a message” to the Kremlin. Two months later, the White House announced new sanctions against a handful of Russian officials and companies, and kicked 35 Russian diplomats out of the country. Six months later, it appears that the message has been thoroughly ignored.

The Russian hackers who gleefully spilled the emails of the DNC, Colin Powell, and the Clinton campaign remain as busy as ever, this time targeting the elections of France and Germany. And that failure to stop Russia’s online adventurism, cybersecurity analysts say, points to a rare sort of failure in digital diplomacy: Even after clearly identifying the hackers behind one the most brazen nation-state attacks against US targets in modern history, America still hasn’t figured out how to stop them.

Poking the Bear

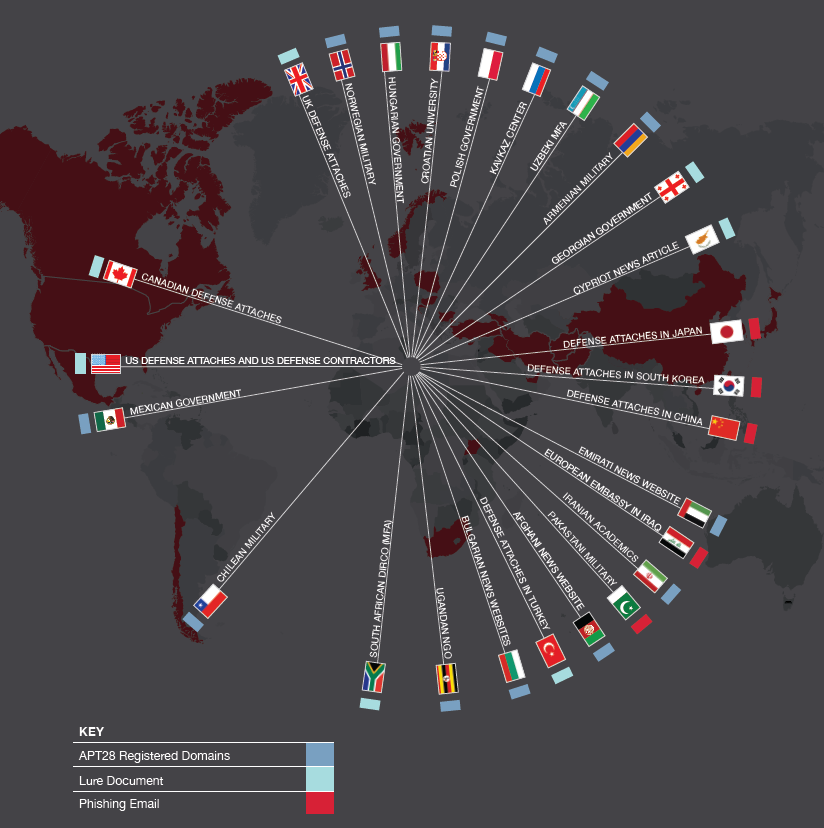

In a recent report tracking the Kremlin-affiliated activity of the hacker group known as Pawn Storm, a.k.a. APT 28 or Fancy Bear, the security firm Trend Micro identified phishing sites that they say were used to target the political campaigns of left-leaning politicians Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel in upcoming French and German elections. The analysts also found that the phishing domains had been registered in March and April of 2017, leaving no doubt the attacks started well after the US government’s attempt at deterrence last year.

“It seems like the opposite effect is happening. There’s definitely not even a slowing down” of the Pawn Storm attacks, says Trend Micro researcher Ed Cabrera. “It’s an emboldening.”

Speaking in a Senate hearing yesterday, FBI director James Comey had no illusions that the Obama administration’s response measures would keep Russian hackers away from future American elections, either. “I think one of the lessons that the Russians may have drawn from this is that this works,” Comey told the Senate Intelligence Committee. “I expect to see them to come back in 2018, and especially in 2020,” for the next US presidential election.

That failure to effectively deter Russia from its attempts at so-called “influence operations” of stealing and leaking documents doesn’t mean deterrence won’t work to stop state-sponsored hacking, says Peter Singer, a strategist at the New America Foundation. It means that the US just hasn’t gone far enough. “Never speak to me of cyber-deterrence if this is how we respond to the most important cyberattack so far in history,” Singer says. “We’ve put out the message not just to APT28 or Russia but any state or non-state attacker that this is going to be low cost, high gain.”

The Obama White House’s move to sanction Russian companies and hackers, eject diplomats and seize two Russian-owned compounds on US soil were “too little, too late,” Singer wrote in testimony to the House Armed Services Committee last month. That reaction, he pointed out, took more than six months to materialize, after even the private-sector cybersecurity community had come to the consensus that Russia was behind the attack. And even those sanctions didn’t cut deep enough for Russia’s highest-level leaders, Singer argues.

Pressure Points

Instead, Singer says, the US should have retaliated in a way that Putin would have felt personally: exposing his hidden personal wealth. “You have to go after the leverage points against the Russian oligarchy,” Singer says. He points to Putin’s fury at the Panama Papers leak from the tax haven law firm of Mossack Fonseca, which revealed portions of the Russian president’s secret wealth. “Reveal where things are hidden,” says Singer. “Make their lives more difficult.”

More broadly, Russian officials fear evidence of their corruption being exposed, says Jim Lewis, a cybersecurity and foreign policy analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. That sort of counter-leak, he says, could be a significant card for the US to play. “We need to think if we want to be more aggressive in our responses,” says Lewis. “We need to think about how to make it more painful for them to continue to do this.”

Last December, in the wake of the sanctions, Lewis told WIRED he felt they were in fact strong enough to rile the Kremlin—he called them the “the biggest retaliatory move against Russian espionage since the Cold War.” However much they may have helped the US though, Lewis says, their deterrent effect doesn’t seem to have extended to US allies like France and Germany. Hence the Pawn Storm hackers’ targeting of the Macron campaign—a hacking attempt Macron’s staff has said failed—as well as German targets including a think tank associated with Germany president Angel Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union party and the German parliament. The latter hack resulted in actual theft of documents that could still be leaked ahead of the country’s September election, in another Russian attempt to destabilize the European Union.

“The Russians appear to have interpreted the sanctions as only applying to actions against the US,” Lewis says. “On a collective level, we need to think about where NATO and the EU can take action.”

Lack of Action

Which raises the third problem with America’s digital diplomatic strategy: President Trump. The Trump administrations weak commitment to European allies, and his softening of Obama’s stance, can only have emboldened Russia further, rather than helping curtail their efforts. Trump has even continued to doubt publicly that the attacks on Democratic targets in the 2016 campaign originated in Russia in the first place, despite his own intelligence officials repeatedly pointing to the Kremlin’s involvement. More than three months after he momentarily conceded Russia’s involvement, Trump earlier this week again floated the unsubstantiated notion it “could’ve been China.”

That lack of commitment to even naming Russia—not to mention deterring its next attack—has left the US on its back foot, says Peter Singer. Even Republican leaders like Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan, who criticized Obama’s sanctions for being too light or too late, Singer points out, are now fighting instead just to maintain sanctions against Russia rather than lift them. “The response to something being too little is to do more, not to do nothing,” says Singer. “And that’s what we’ve done since.”

All of which means the notion of deterring Russian attacks on elections or civil society is, for the moment, defunct. Expect the Kremlin’s habit of electoral-meddling will get worse before it gets better—until someone gives them a reason not to.

***  FireEye

FireEye

Meanwhile, Germany looks to take a more aggressive posture against Russian intrusion.

The head of Germany’s domestic intelligence agency accused Russian rivals of gathering large amounts of political data in cyber attacks and said it was up to the Kremlin to decide whether it wanted to put it to use ahead of Germany’s September elections….

Hans-Georg Maassen, president of the BfV agency, said “large amounts of data” were seized during a May 2015 cyber attack on the Bundestag, or lower house of parliament, which has previously been blamed on APT28, a Russian hacking group….

Germany’s top cyber official last week confirmed attacks on two foundations affiliated with Germany’s ruling coalition parties that were first identified by security firm Trend Micro.

“We recognize this as a campaign being directed from Russia. Our counterpart is trying to generate information that can be used for disinformation or for influencing operations,” he said. “Whether they do it or not is a political decision … that I assume will be made in the Kremlin.”

Maassen said it appeared that Moscow had acted in a similar manner in the United States, making a “political decision” to use information gathered through cyber attacks to try to influence the U.S. presidential election.

Berlin was studying what legal changes were needed to allow authorities to purge stolen data from third-party servers, and to potentially destroy servers used to carry out cyber attacks.

“We believe it is necessary that we are in a position to be able to wipe out these servers if the providers and the owners of the servers are not ready to ensure that they are not used to carry out attacks,” Maassen said….

He said intelligence agencies knew which servers were used by various hacker groups, including APT10, APT28 and APT29.