The highways in the United States belonged to El Chapo.

CatholicOnline: The cartel has such momentum trafficking heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, and marijuana from Mexico to the United States, that despite El Chapo’s incarceration in a Mexican prison, the cartel continued all operations.

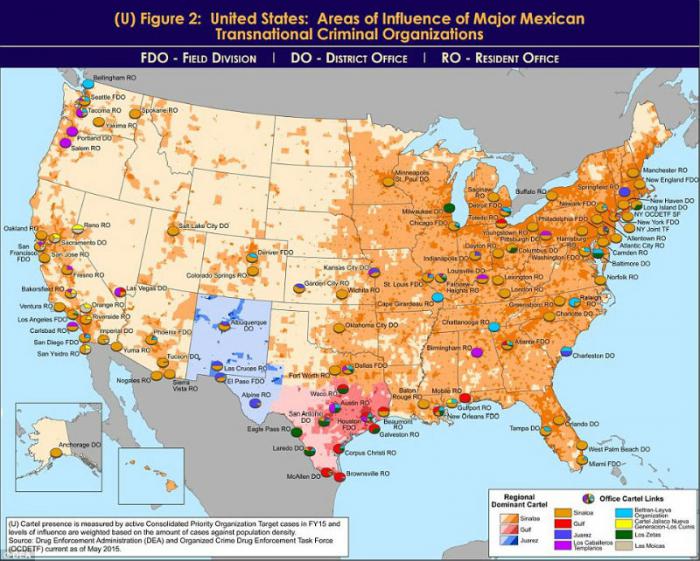

The DEA report shows the Sinaloa cartel “maintains the most significant presence in the United States,” adding, “Mexican TCOs pose the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States; no other group is currently positioned to challenge them.”

Mexico seizes El Chapo’s planes, cars, houses

MEXICO CITY — As the hunt for fugitive drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán intensifies, Mexican authorities recently announced they have confiscated 11 planes, eight vehicles and six houses belonging to the kingpin in the past five months.

That’s likely just a fraction of the assets Guzmán has accumulated during his life of crime. The Sinaloa Cartel he oversees traffics billions of dollars worth of narcotics to the United States every year, according to estimates from the Justice Department and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The yawning gap between the seizures and Guzmán’s potential riches underscores a growing concern here: Why the Mexican government can’t or won’t seize more of Guzman’s ill-gotten gains. The problem, critics say, is a lack of laws with teeth, and the motivation to change that.

“Mexico is a weak state that has yet to form a political will around the implementation of such laws,” said lawyer Edgardo Buscaglia, who has addressed the Mexican Senate on asset forfeitures.

One issue is a 2009 law that was meant to give authorities broader powers to seize drug cartel members’ assets. Instead, the law allows only the attorney general — as opposed to local prosecutors — to confiscate assets, meaning that federal authorities are overburdened and cases routinely slip through the net.

The overall result is far fewer successfully prosecuted cases against organized crime — a total of 43 in the past six years in Mexico, about the same number neighboring Guatemala achieves each year, according to a Mexican Senate report.

The law also requires property owners to be sentenced before authorities can take their assets, delaying seizures by months or even years. Many cases collapse.

“Attacking criminal groups financially by pursuing the properties and firms that provide them with financial and logistical support is an essential part of the fight against organized crime,” said Antonio Mazzitelli, Latin American representative of the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime. “In Mexico, they put a criminal in jail, and nothing happens.”

Since 2007, the Treasury Department has banned 95 Mexican companies and hundreds more individuals linked to El Chapo’s drug empire from operating in the United States. All continue to operate freely in Mexico, however.

Last year, an American grand jury indicted Ignacio Muñoz Orozco, the owner of a Mexican clothing chain, on money laundering charges related to the Sinaloa Cartel. Orozco served as a higher-level official in the federal Social Development Ministry in the mid-2000s and has yet to be charged with a crime in Mexico.

“There are thousands of such cases that Mexican prosecutors decline to pursue,” Buscaglia said.

Guzman’s case underscores the nature of corruption in the country, where watchdog group Transparency International reports criminals have “captured” public institutions.

The drug kingpin escaped from a maximum security prison in July using a mile-long tunnel. Police have arrested the prison governor and several guards in connection with the breakout.