Obama started off his speech by saying death fell from the sky. Sigh…. What is more interesting is part of his speech in both audio and text that has been published has been edited already. The sentence that has been removed by most sites is this:

“Let all the souls here rest in peace, for we shall not repeat the evil,” the president said. “We come to ponder the terrible force unleashed in the not so distant past. We come to mourn the dead.”

Evil?

Well there are some facts that the Obama White House protocol office and speechwriters clearly don’t know about that day Japan surrendered, where General McArthur crafted a well organized day demonstrating the full might of the United States and her military in the face of the Japanese aboard our battleship.

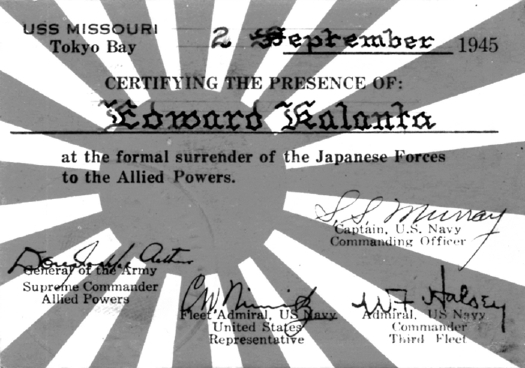

Every one of the Missouri’s crew received a card like this for taking part in the surrender in Tokyo Bay almost 59 years ago.

Tokyo Bay at the signing of the surrender by Japan:

Japan’s formal capitulation to the Allies climaxed a week of historic events as the initial steps of the occupation program went into effect. The surrender ceremony took place aboard the Third Fleet flagship, U. S. S. Missouri, on the misty morning of Sunday, 2 September 1945. As the Missouri lay majestically at anchor in the calm waters of Tokyo Bay, convoys of large and small vessels formed a tight cordon around the surrender ship, while army and navy planes maintained a protective vigil overhead. This was the objective toward which the Allies had long been striving-the unconditional surrender of the previously undefeated military forces of Japan and the final end to conflict in World War II.

The decks of the Missouri that morning were crowded with the representatives of the various United Nations that had participated in the Pacific War. Outstanding among the Americans flanking General MacArthur were Admirals Nimitz and Halsey, and General Wainwright who had recently been released from a Manchurian internment camp, flown to Manila, and then brought aboard to witness the occasion. Present also were the veteran staff members who had fought with General MacArthur since the early dark days of Melbourne and Port Moresby.

Shortly before 0900 Tokyo time, a launch from the mainland pulled alongside the great United States warship and the emissaries of defeated Japan climbed silently and glumly aboard. The Japanese delegation included two representatives empowered to sign the Instrument of Surrender, Mamoru Shigemitsu, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu of the Imperial General Staff, in addition to three representatives from the Foreign Office, three representatives from the Army, and three representatives from the Navy.68

As Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, General MacArthur presided over the epoch-making ceremony, and with the following words he inaugurated the proceedings which would ring down the curtain of war in the Pacific:

We are gathered here, representatives of the major warring powers, to conclude a solemn agreement whereby peace may be restored. The issues, involving divergent ideals and ideologies, have been determined on the battlefields of the world and hence are not for our discussion or debate. Nor is it for us here to meet, representing as we do a majority of the people of the earth, in a spirit of distrust, malice or hatred. But rather it is for us, both victors and vanquished, to rise to that higher dignity which alone befits the sacred purposes we are about to serve, committing all our peoples unreservedly to faithful compliance with the understandings they are here formally to assume.

It is my earnest hope, and indeed the hope of all mankind, that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past-a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance and justice.

The terms and conditions upon which surrender of the Japanese Imperial Forces is here to be given and accepted are contained in the instrument of surrender now before you ….69

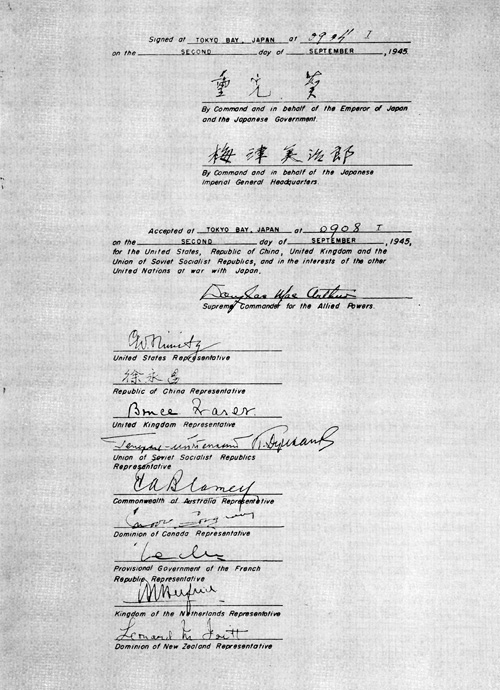

The Supreme Commander then invited the two Japanese plenipotentiaries to sign the duplicate surrender documents: Foreign Minister Shigemitsu, on behalf of the Emperor and the Japanese Government, and General Umezu, for the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters. He then called forward two famous former prisoners of the Japanese to stand behind him while he himself affixed his signature to the formal acceptance of the surrender: Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright, hero of Bataan and Corregidor and Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur E. Percival, who had been forced to yield the British stronghold at Singapore.

General MacArthur was followed in turn by Admiral Nimitz, who signed on behalf of the United States, and by the representatives of the other United Nations present: Gen. Hsu Yung-Chang for China, Adm. Sir Bruce Fraser for the United Kingdom, Lt. Gen. Kuzma N. Derevyanko for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Gen. Sir Thomas A. Blarney for Australia, Col. L. Moore-Cosgrave for Canada, Gen. Jacques P. LeClerc for France, Adm. Conrad E. L. Helfrich for the Netherlands, and Air Vice-Marshall Leonard M. Isitt for New Zealand.

The Instrument of Surrender was completely signed within twenty minutes. (Plate No. 132) The first signature of the Japanese delegation was affixed at 0904; General MacArthur wrote his name at 0910; and the last of the Allied representatives signed at 0920. The Japanese envoys then received their copy of the surrender document, bowed stiffly and departed for Tokyo. Simultaneously, hundreds of army and navy planes roared low over the Missouri in one last display of massed air might.

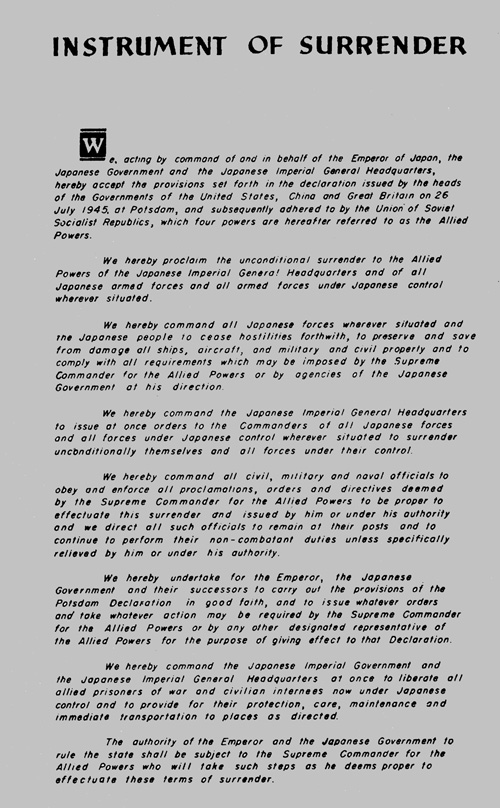

In signing the Instrument of Surrender, the Japanese bound themselves to accept the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, to surrender unconditionally their armed forces wherever located, to liberate all internees and prisoners of war, and to carry out all orders issued by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers to effectuate the terms of surrender.

On that same eventful day, the Supreme Commander broadcast a report to the people of the United States. Having been associated with Pacific events since the Russo-Japanese war, General MacArthur was able to speak with the authority of long experience to forecast a future for Japan:

We stand in Tokyo today reminiscent of our countryman, Commodore Perry, ninety-two years ago. His purpose was to bring to Japan an era of enlightenment and progress by lifting the veil of isolation to the friendship, trade and commerce of the world. But, alas, the knowledge thereby gained of Western science was forged into an instrument of oppression and human enslavement. Freedom of expression, freedom of action, even freedom of thought were denied through supervision of liberal education, through appeal to superstition and through the application of force. We are committed by the Potsdam Declaration of Principles to see that the Japanese people are liberated from this condition of slavery. It is my purpose to implement this commitment just as rapidly as the armed forces are demobilized and other essential steps taken to neutralize the war potential. The energy of the Japanese race, if properly directed, will enable expansion vertically rather than horizontally. If the talents of the race are turned into constructive channels, the country can lift itself from its present deplorable state into a position of dignity….70

Immediately following the signing of the surrender articles, the Imperial Proclamation of capitulation was issued. The Proclamation, the draft of which had been given to General Kawabe at Manila, read as follows:

Accepting the terms set forth in the Declaration issued by the heads of the Governments of the United States, Great Britain and China On July 26th 1945 at Potsdam and subsequently adhered to by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, We have commanded the Japanese Imperial Government and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters to sign on Our behalf the instrument of surrender presented by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and to issue General Orders to the Military and Naval forces in accordance with the direction of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.

We command all Our people forthwith to cease hostilities, to lay down their arms and faithfully to carry out all the provisions of the Instrument of Surrender and the General Orders issued by the Japanese Imperial Government and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters hereunder.71

1. Although the formal surrender of Japan did not occur until September 2, 1945 aboard the U.S.S. Missouri, the occupation of that nation began five days earlier when a team of 150 American personnel arrived at Atsugi airfield on August 28. They were originally supposed to arrive on August 25 but a Japanese delegation in Manila informed the Americans that several more day were needed to ensure that military resistors to the surrender could be disarmed. They were correct since a few days before the Americans arrived, Japanese pilots took off from Atsugi airfield and dropped leaflets on Tokyo and other cities urging resistance by the civilians. Fortunately those pilots were gone, along with any resistance, by the time the Americans arrived at Atsugi.

2. The surrender ceremony aboard the U.S.S. Missouri on September 2 was carefully planned…except for one small but very important detail. The fancy British mahony table brought aboard the Missouri for the surrender was too small for the two large documents that had to be signed. In desperation, an ordinary table from the crew’s mess was drafted as a replacement. It was covered by a green coffee-stained tablecloth from a wardroom. After the 2 surrender documents were signed on the table, it was returned to the mess and was being set for lunch until the ship’s captain and others realized it was an historical object and removed for posterity.

3. There were 280 allied warships in Tokyo Bay when the surrender took place but no aircraft carriers. They were out at sea as a reserve force just in case the Japanese changed their minds.

4. There was a thick cover of low dark clouds over Tokyo Bay during the 20 minute surrender ceremony. Unfortunately, 2000 planes were scheduled to fly over the bay the moment the ceremony finished. However, at the last moment the clouds suddenly parted, as if in a Hollywood movie production, and the sun burst through allowing all aboard the U.S.S. Missouri to view the mightiest display of air power ever seen.

5. When Emperor Hirohito announced over the radio the acceptance of the allied terms of surrender on August 15 (Tokyo time), very few Japanese listening to him understood what he was saying because he was using formal formal court language not used by the general populace. It wasn’t until the radio announcers followed up by describing what he said that the public understood what he meant.

6. After Emperor Hirohito made his surrender announcement, the Japanese public ran through a gamut of emotions…anger, despair, sadness, and relief. However, one Japanese person had a very different thought on his mind…how to make money off the surrender. He was Ogawa Kikumatsu, a book editor. Ogawa was on a business trip when the surrender was announced on the radio. He immediately returned to Tokyo by train and while traveling he began thinking of how to take advantage of the impending occupation.. By the time he reached Tokyo, he had his idea…to publish a guide booklet of Japanese phrases translated into English with the aid of phonetics. It took less than three days for Ogawa and his team to prepare the 32 page booklet and it was published exactly a month after the surrender. Its first run of 300,000 copies sold out immediately and by the end of 1945, 3.5 million copies had been sold.