Washington, D.C., April 24, 2017 – Ten years ago, Chiquita Brands International became the first U.S.-based corporation convicted of violating a U.S. law against funding an international terrorist group—the paramilitary United Self-defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). But punishment for the crime was reserved only for the corporate entity, while the names of the individual company officials who engineered the payments have since remained hidden behind a wall of impunity.

As Colombian authorities now prepare to prosecute business executives for funding groups responsible for major atrocities during Colombia’s decades-old conflict, a new set of Chiquita Papers, made possible through the National Security Archive’s FOIA lawsuit, has for the first time made it possible to know the identities and understand the roles of the individual Chiquita executives who approved and oversaw years of payments to groups responsible for countless human rights violations in Colombia.

Today’s posting features the first in a series of articles published jointly by the National Security Archive and Verdad Abierta highlighting new revelations from the Chiquita Papers, identifying the people behind the payments, and examining how the Papers can help to clarify lingering questions about the case.

* * *

The New Chiquita Papers: Secret Testimony and Internal Records Identify Banana Executives who Bankrolled Terror in Colombia

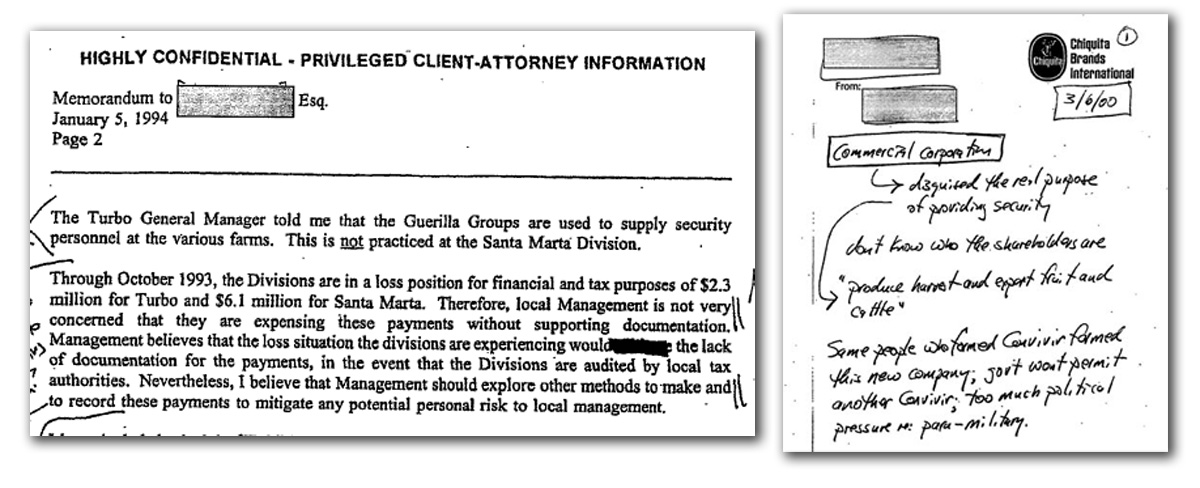

In the last few years of the 1990s, Chiquita Brands International, the U.S.-based fruit company, fell under a cloud of suspicion. An exposé in the Cincinnati Enquirer, the company’s hometown paper, revealed some of the banana giant’s dirtiest secrets—among them: the messy fallout from bribes paid to Colombian customs agents by officials at Banadex, Chiquita’s wholly-owned Colombian subsidiary.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—the U.S. financial crimes watchdog—was also looking into the bribery allegations. The agency subpoenaed thousands of Chiquita’s internal records and soon made a startling discovery. Tucked away in the same accounts where Chiquita concealed the bribes were millions of dollars in additional payments to a rogues’ gallery of armed groups, including leftist insurgents, right-wing paramilitaries, notorious army brigades, and the controversial, but government-approved, “Convivir” militias.

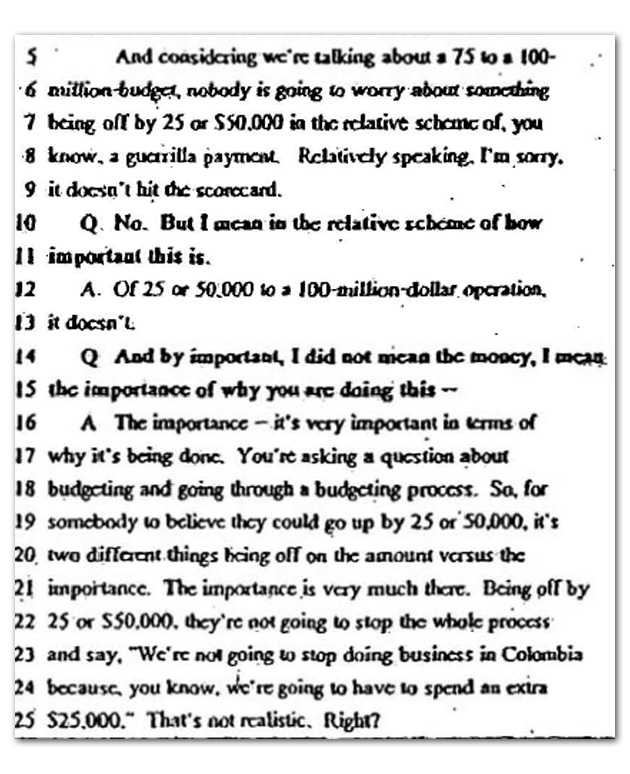

With these documents in hand, the SEC deposed seven Chiquita executives, each of whom played a different role in administering the so-called “sensitive payments.” In secret testimony on January 6, 2000 Robert F. Kistinger, head of Chiquita’s Banana Group based in Cincinnati, Ohio, told the SEC he had direct knowledge about many of the payments to armed groups, especially when they began in the late 1980s, but claimed that he had become less and less involved with the specifics over time. In his view, the amounts of money paid to the groups—hundreds of thousands of dollars per year—were simply not large enough to affect the company’s bottom line.

Kistinger, who is a named defendant in a massive civil litigation case pending against former Chiquita executives in U.S. federal court, and a likely target of future investigations in Colombia, said it was “not realistic” to halt Chiquita’s Colombia operations over such insignificant amounts of money. “I’m sorry,” he said, “it doesn’t hit the scorecard.”

“We’re not going to stop doing business in Colombia, because, you know, we’re going to have to spend an extra $25,000. That’s not realistic. Right?”

In 2013, Chiquita brought a rarely-seen “reverse” Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit against the SEC in an effort to block the agency from releasing transcripts of these depositions (and thousands of additional documents) to the National Security Archive, a non-governmental research group based in Washington, D.C. Two years later, a federal appeals court panel rejected Chiquita’s claim, clearing the way for the release of more than 9,000 pages of the company’s most sensitive internal records.

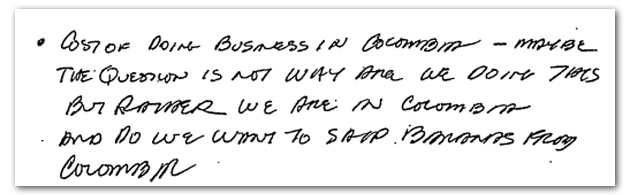

It’s easy to see why the company would want to keep them under wraps. The secret, sworn statements from the SEC probe are the de facto oral history of Chiquita’s ties to terrorist groups in Colombia—a unique and damning firsthand account of how one multinational corporation developed and routinized a system of secret transactions with actors on all sides of the conflict in order to maintain normal business operations—even thrive—in one of the most conflictive regions of the world, all the while treating the payments as little more than the “cost of doing business in Colombia.”[1]

This article is the first in a series from the National Security Archive and Verdad Abierta, the award-winning Colombian news website, highlighting new revelations from the Chiquita Papers, identifying the people behind the payments, and examining how the Papers can help to clarify lingering questions about the case. What was behind Chiquita’s decision to wind down payments to guerrillas and increase payments to their right-wing rivals? Exactly how much money did Chiquita pay to the various armed groups? What was the role of the Colombian security forces in encouraging the tilt toward paramilitaries? Did Chiquita knowingly fund specific acts of violence? And at what point did employees and executives with knowledge of the payments understand that the company was dealing with paramilitary death squads and not a government-sponsored militia group?

* * *

The new set of Chiquita Papers has for the first time made it possible to know the identities and understand the roles played by individual Chiquita executives like Kistinger who approved and oversaw years of payments to groups responsible for countless human rights violations in Colombia. These records are of particular importance now that Colombian authorities have signaled that they are prepared to prosecute business executives for funding groups that committed war crimes and other atrocities during the conflict.

Ten years ago, Chiquita became the first major multinational corporation convicted of “engaging in transactions with a specially-designated global terrorist.” In a March 2007 sentencing agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Chiquita admitted transferring some $1.7 million[2] to the United Self-defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) from September 10, 2001, when the group was first named on the U.S. State Department’s terrorist list, through June 2004, when the payments ceased.

Even after outside attorneys warned in February 2003 that it “[m]ust stop payments” to the outlaw paramilitary organization, Chiquita continued to pay the AUC for another 16 months. Until that point, Chiquita’s strategy, set forth by senior executives in Cincinnati, was to “just let them sue us, come after us.”[3]

The AUC was a loose federation of rightist militants and drug traffickers responsible for a terrible legacy of violent acts in Colombia going back to the 1980s. Chiquita began to pay the AUC sometime in 1996-1997, just as the group launched a nationwide campaign of assassinations and massacres aimed at unionists, political activists, public officials and other perceived guerrilla supporters, often working with the collaboration or complicity of Colombian security forces. Over the next several years, the AUC dramatically increased its numbers and firepower, raised its political profile, infiltrated Colombian institutions, drove thousands of Colombians from their homes, and for the first time challenged guerrilla groups for control of strategic areas around the country.

Chiquita agreed to pay a relatively modest $25 million fine as part of its deal with the DOJ, but not a single company executive has ever been held responsible for bankrolling the AUC’s wave of terror. Nor have any Chiquita officials faced justice for millions more in outlays to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and practically every other violent actor in the region.

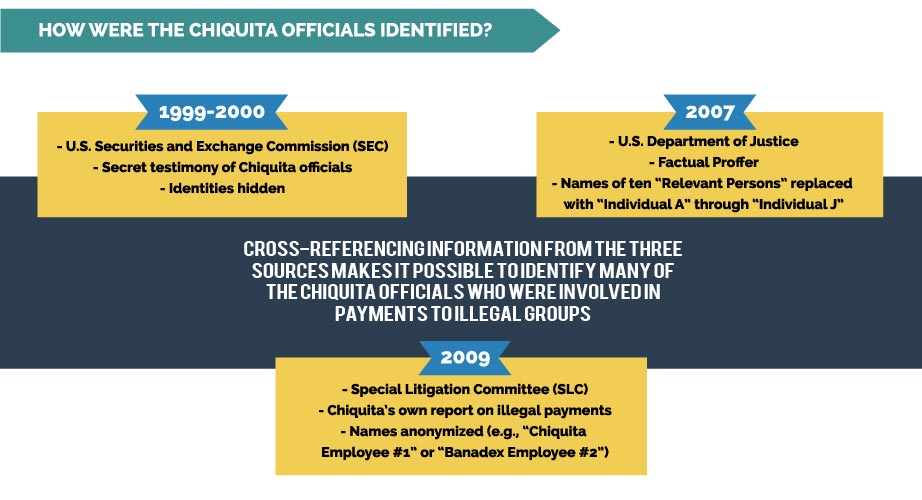

Efforts to hold individual Chiquita executives accountable for financing the groups are complicated by a deliberate decision on the part of the U.S. Justice Department to withhold the names of the people behind the payments scheme. At the September 2007 sentencing hearing in the terror payments case, U.S. government attorneys specifically argued against the public identification of the Chiquita officials “to protect the reputational and privacy interests of uncharged individuals.”

Instead, the Factual Proffer memorializing the plea agreement revolves around ten anonymous “Relevant Persons” identified only as “Individual A” through “Individual J.” The public version of a 2009 report by Chiquita’s Special Litigation Committee (SLC) likewise omits the names of most of the individuals identified in the report, replacing them with anonyms like “Chiquita Employee #2,” “Banadex Employee #1,” and “Chiquita lawyer.”

In 2011, the Archive published its first Chiquita Papers, posting, revealing, among other things, that the company appeared to have engaged in quid pro quos with guerrilla and paramilitary groups in Colombia, contrary to the Factual Proffer’s finding that Chiquita had not derived any benefit from the payments.

The original Chiquita Papers revealed the company had engaged in quid pro quos with guerilla and paramilitary forces in Colombia

The first Chiquita Papers collection offered some important new revelations, but lacked a coherent contextual narrative. There were few indications as to who had written the documents, and it was nearly impossible to say for sure how the named individuals related to one another. Handwritten notes, auditing records, legal memos, and accounting schedules—among thousands of pages of internal records released under FOIA by the DOJ—offered tantalizing clues, but few concrete conclusions could be drawn from them.

The key that unlocks many of the mysteries of the Chiquita Papers is the secret testimony given by Kistinger and six other Chiquita officials during the SEC’s expansive bribery investigation. Through a relatively simple, if laborious, process of cross-referencing among the three sources, it is possible to identify almost all of the individuals whose names were scrubbed from the Factual Proffer, the SLC Report, and the SEC testimony—effectively stripping away the redactions that have shielded Chiquita personnel from scrutiny and that have helped guarantee impunity for individuals linked to the payments.