Trump must decide if he wants to continue on the current course, which relies on a relatively small US-led NATO force to help Afghan partners push back the Taliban, or if he wants to try a new tack such as adding more forces — or even withdrawing altogether.

“Heading to Camp David for major meeting on National Security, the Border and the Military (which we are rapidly building to strongest ever),” Trump said on Twitter ahead of his Friday afternoon arrival.

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis had initially promised to provide a new plan for Afghanistan by mid-July.

But Trump appears dissatisfied by initial proposals to add a few thousand more troops, and the strategy has been expanded to include the broader South Asia region, notably Pakistan.

In a sign of Trump’s frustration, the president reportedly told Mattis and General Joe Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, they should replace General John Nicholson, who heads up US and NATO forces in Afghanistan.

Mattis has come to his general’s defense, saying this week he “is our commander in the field. He has the confidence of NATO, he has the confidence of Afghanistan, he has the confidence of the United States.”

In the past year (6/30/2016 to 6/30/2017) 17 US service members died in Afghanistan, and 41 DOD contractors.

One big topic of discussion will be the recent proposals to privatize the war in Afghanistan presented by two different businessmen, Eric Prince and Stephen Feinberg.

Under Prince’s plan, the viceroy would be a federal official who reports to the president and is empowered to make decisions about State Department, DoD, and intelligence community functions in-country. Prince was vague about how exactly this would work and which agency would house the viceroy, but compared the job to a “bankruptcy trustee” and said the person would have full hiring and firing authority over U.S. personnel. Prince wants to embed “mentors” into Afghan battalions. These mentors would be contractors from the U.S., Britain, Canada, South Africa—“anybody with a good rugby team,” Prince quipped. Prince also wants a “composite air wing”—a private air force—to make up for deficiencies in the Afghan air capabilities.

“The adults hate it,” said a congressional aide who has seen the plan, referring to McMaster, Mattis, and White House Chief of Staff John Kelly. Mattis acknowledged that his analysis of the problems in Afghanistan is correct, Prince claimed, while disagreeing on his recommendations. On Monday, Mattis confirmed in a press gaggle that the contracting proposals were under consideration. A Pentagon spokesperson didn’t immediately return a request for comment.

Feinberg, on the other hand, has met with Trump, as well as with Kushner. One senior administration official said Feinberg has met more than once with Trump in the Oval Office. Through his investment firm Cerberus Capital, Feinberg controls the huge military contractor Dyncorp. He is also a confidant of Trump and has known him from business circles since before Trump became president. Feinberg was considered for a czar-type position overseeing an intelligence review earlier this year, but the idea was stymied by a vehement backlash from the intelligence community. Feinberg does not have an intelligence background.

Feinberg is proposing ideas similar to Prince’s; Prince said the two were 95 to 98 percent in agreement, though “he wrote his thing, I wrote mine.”

A source close to the situation said Feinberg had been asked to submit a “strategic recommendation” for Afghanistan that is “materially different with respect to the use of independent contractors from the plan Erik Prince proposed.”

Sean McFate, a Georgetown professor and former DynCorp contractor, described Feinberg’s plan for contractors as “more status quo. He wants to take the current mission and just make it bigger.”

One of the issues raised by Prince’s plan is that U.S. law prohibits using contractors for combat operations. The workaround is that instead of being categorized under Title 10 of the U.S. code, it will be housed under Title 50, making it subject to the same regulations as intelligence operations. This has sparked concerns about transparency, but appeals to some in the secretive intelligence community.

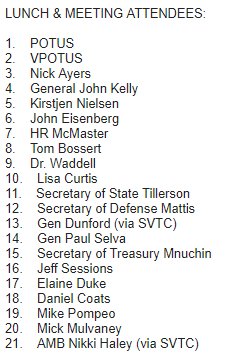

Critics say Prince’s plan will lead to a moral and legal quagmire, as contractors from around the world fighting in place of U.S. forces present a host of possible problems. What happens if a Canadian, for example, kills an Afghan civilian while fighting as a contractor under the leadership of the American “viceroy”? What if the contractors get in a real bind—does the U.S. send our military in to help them? Read the full text here for additional names and context.