WASHINGTON — Russia conducted its second test this year of a direct ascent anti-satellite missile test, according to a U.S. Space Command, yet again drawing sharp criticism from the U.S.

“Russia has made space a war-fighting domain by testing space-based and ground-based weapons intended to target and destroy satellites. This fact is inconsistent with Moscow’s public claims that Russia seeks to prevent conflict in space,” said Space Command head Gen. James Dickinson in a statement. “Space is critical to all nations. It is a shared interest to create the conditions for a safe, stable and operationally sustainable space environment.”

Space Command said the direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tested is a kinetic weapon capable of destroying satellites in low Earth orbit. A similar anti-satellite missile test by India in March 2019 that destroyed the nation’s own satellite on orbit drew criticism from observers, who noted that the debris created from the threat could cause indirect damage to other satellites.

Russia has completed tests of its Nudol ballistic-missile system several times in recent years, including in April of this year. Nudol can be used as an anti-satellite weapon and is capable of destroying satellites in low Earth orbit. According to the CSIS Aerospace Security Project’s “Space Threat Assessment 2020,” Russia conducted its seventh Nudol test in 2018.

Under the Trump administration, the U.S. has used the development and testing of anti-satellite weapons by Russia and China as a justification for creating both Space Command and the U.S. Space Force in 2019.

“The establishment of U.S. Space Command as the nation’s unified combatant command for space and U.S. Space Force as the primary branch of the U.S. Armed Forces that presents space combat and combat support capabilities to U.S. Space Command could not have been timelier. We stand ready and committed to deter aggression and defend our nation and our allies from hostile acts in space,” Dickenson said.

Acting Secretary of Defense Christopher C. Miller made similar comments last week as the White House released a new National Space Policy, which calls for the U.S. to defeat aggression and promote norms of behavior in space

“Our adversaries have made space a war-fighting domain, and we have to adapt our national security organizations, policies, strategies, doctrine, security classification frameworks and capabilities for this new strategic environment. Over the last year we have established the necessary organizations to ensure we can deter hostilities, demonstrate responsible behaviors, defeat aggression and protect the interests of the United States and our allies.”

***

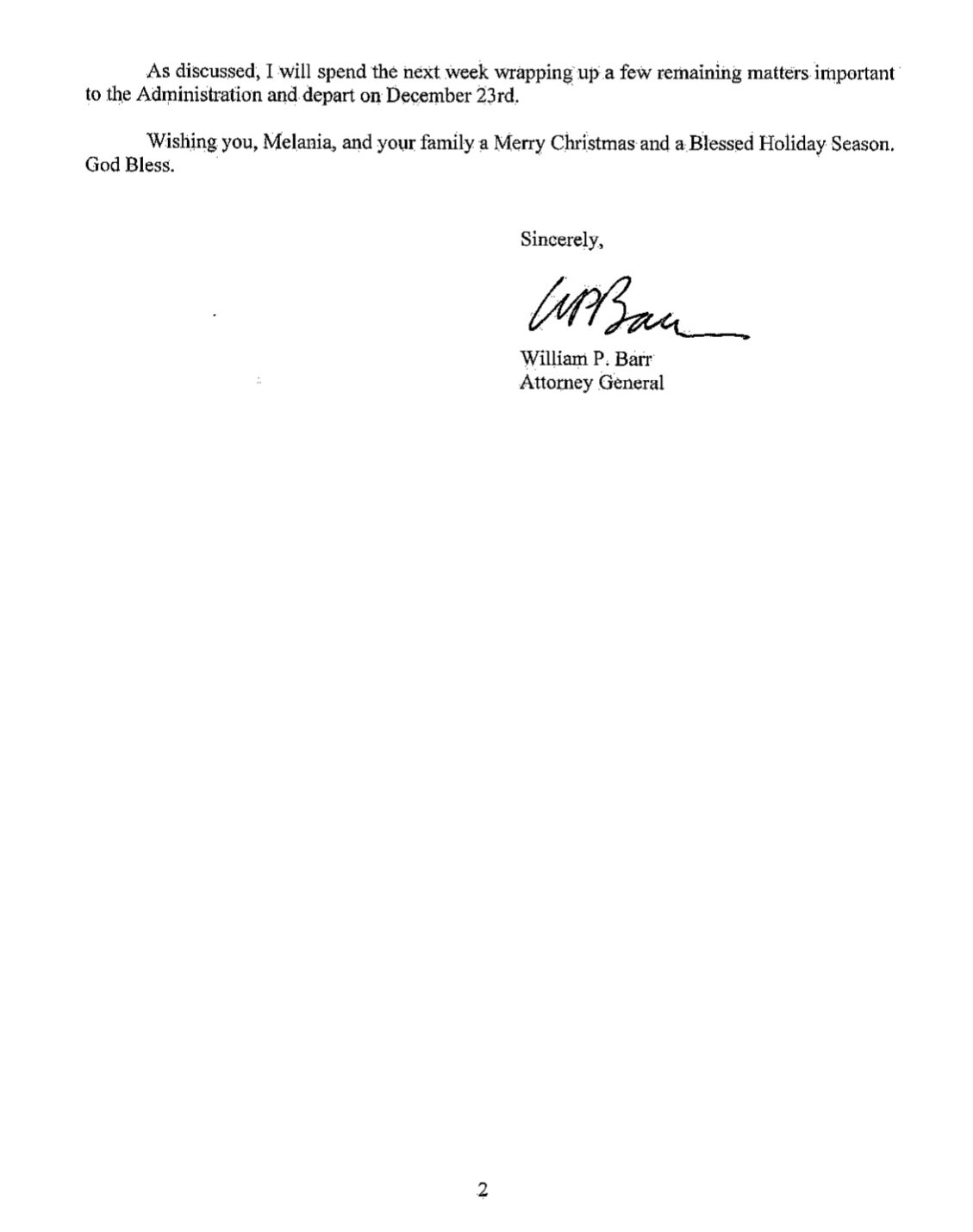

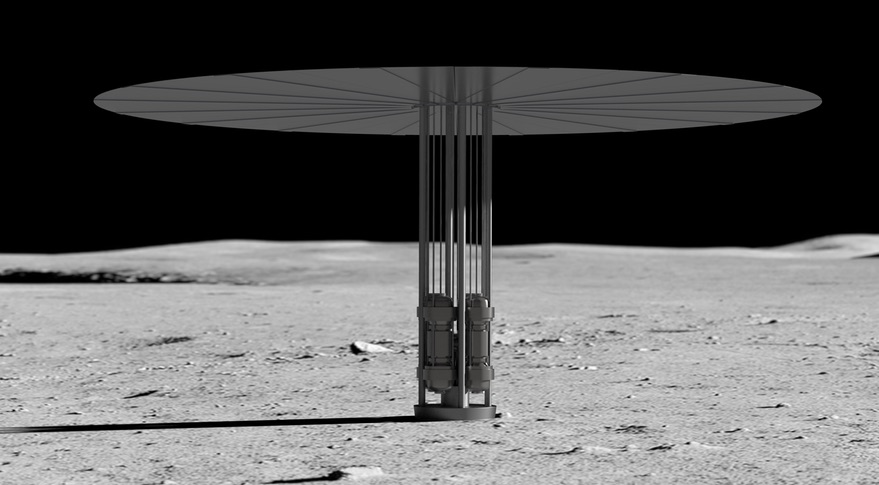

An illustration of a Kilopower nuclear reactor on the moon. Development of surface nuclear power technologies is a key element of the roadmap included in Space Policy Directive 6. Credit: NASA

An illustration of a Kilopower nuclear reactor on the moon. Development of surface nuclear power technologies is a key element of the roadmap included in Space Policy Directive 6. Credit: NASA

The White House released a new space policy directive Dec. 16 intended to serve as a strategic roadmap for the development of space nuclear power and propulsion technologies.

Space Policy Directive (SPD) 6, titled “National Strategy for Space Nuclear Power and Propulsion,” discusses responsibilities and areas of cooperation among federal government agencies in the development of capabilities ranging from surface nuclear power systems to nuclear thermal propulsion, collectively known as space nuclear power and propulsion (SNPP).

“This memorandum establishes a national strategy to ensure the development and use of SNPP systems when appropriate to enable and achieve the scientific, exploration, national security, and commercial objectives of the United States,” the 12-page document states.

SPD-6 sets out three principles for the development of space nuclear systems: safety, security and sustainability. It also describes roles and responsibilities for various agencies involved with development, use or oversight of such systems.

Much of the document, though, is a roadmap for the development of nuclear power and propulsion systems. It sets a goal of, by the mid-2020s, developing uranium fuel processing capabilities needed for surface power and in-space propulsion systems. By the mid to late 2020s, NASA would complete the development and testing of a surface nuclear power system for lunar missions that can be scalable for later missions to Mars.

SPD-6 calls for, by the late 2020s, establishing the “technical foundations and capabilities” needed for nuclear thermal propulsion systems. It also sets a goal of developing advanced radioisotope power systems, versions of radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) long used on NASA missions, by 2030.

Many of the initiatives outlined in SPD-6 are already in progress. NASA has been working with the Department of Energy (DOE) on a project called Kilopower to develop surface nuclear reactors, including efforts to seek proposals to develop a reactor for use on the moon. NASA has also been studying nuclear thermal propulsion, an initiative backed by some in Congress who have set aside funding in NASA’s space technology program for that effort.

“We have these individual initiatives going on — nuclear thermal power, the Kilopower activities — and what we’re trying to do is pull together a common operating picture for Defense, NASA and DOE,” said a senior administration official, speaking on background about SPD-6.

That roadmap and schedule is also intended to prioritize those activities. Surface nuclear power is needed in the nearer term to support lunar missions later in the decade, particularly to handle the two-week lunar night. Nuclear thermal propulsion, as well as alternative nuclear electric propulsion technologies, are less critical since they are primarily intended to support later missions to Mars.

“Those things are important for going to Mars,” the official said of nuclear propulsion, “but first we’re doing the moon and leveraging terrestrial capabilities and technologies to put that foothold on the moon.”

Another issue addressed in SPD-6 is the use of different types of uranium. Tests in 2018 as part of the Kilopower program used highly enriched uranium, or HEU. That project, and discussions by NASA and DOE to use HEU for flight reactors, raised concerns in the nuclear nonproliferation community. They were worried that it could set a precedent for renewed production of HEU, which is also used in nuclear weapons.

SPD-6 restricts, but does not prohibit, the use of HEU in space nuclear systems. “Before selecting HEU or, for fission reactor systems, any nuclear fuel other than low-enriched uranium (LEU), for any given SNPP design or mission, the sponsoring agency shall conduct a thorough technical review to assess the viability of alternative nuclear fuels,” it states.

“We want to keep those proliferation concerns foremost in our minds,” a senior administration official said. “We don’t want to necessarily rule out HEU if that’s the only way to get a mission about, but we want to be very deliberate about it.”

The policy, an official said, “sets an extremely high bar” for non-defense use of HEU on space systems, citing progress on high-assay low enriched uranium, which can provide power levels similar to HEU systems with only a modest mass penalty.

The White House released SPD-6 a week after it issued a new national space policy during a meeting of the National Space Council. That broader policy briefly addressed space nuclear power and propulsion, discussing roles for various agencies, but did not mention the roadmap or other details found in SPD-6.

Many thought the release of the national space policy would conclude the administration’s work on space policy, making SPD-6 something of a surprise. A senior administration official said work on various space policy directives and the national space policy had been slowed down by the coronavirus pandemic, but wouldn’t rule out additional announcements in the remaining five weeks of the Trump administration.

An illustration of a Kilopower nuclear reactor on the moon. Development of surface nuclear power technologies is a key element of the roadmap included in Space Policy Directive 6. Credit: NASA

An illustration of a Kilopower nuclear reactor on the moon. Development of surface nuclear power technologies is a key element of the roadmap included in Space Policy Directive 6. Credit: NASA