On the Road to Mosul With Iraq’s Golden Brigade

Elite Iraqi troops retake town of Bartella

by MATT CETTI-ROBERTS

WiB: A soldier from the Iraqi Army’s Golden Brigade ushers a party of journalists down a dusty side street in the town of Bartella and points to a flattened pile of concrete. The rubble is all that’s left of a building after a coalition air strike.

When the bomb hit, at least one Islamic State militant was hiding in the structure. We know this because a large blackened piece of a foot lies baking in the midday sun.

It has been sitting there for at least two days. The smell is ripe.

One member of our group, a translator called Ali, starts happily taking pictures with his iPhone. Six months ago, he barely escaped Mosul with his wife and children.

The journey involved sneaking through Islamic State lines and luckily finding a safe path through the minefields that surround Iraq’s second largest city. Ali still has relatives living in Mosul under the brutal terrorist group’s rule.

For him, this is personal.

On Oct. 21, 2016, the Golden Brigade, one of Iraq’s elite special operations units, recaptured Bartella. Islamic State fighters took over the town as they pushed into the Nineveh plains in August 2014. At that time, approximately 30,000 Iraqis lived here, mainly Christians and Assyrians.

Situated on the main highway between Erbil and Mosul, Bartella is a strategic point. On Oct. 17, 2016, the Iraqi Army’s started down the route as part of a multi-pronged push towards Islamic State’s de facto capital in the country.

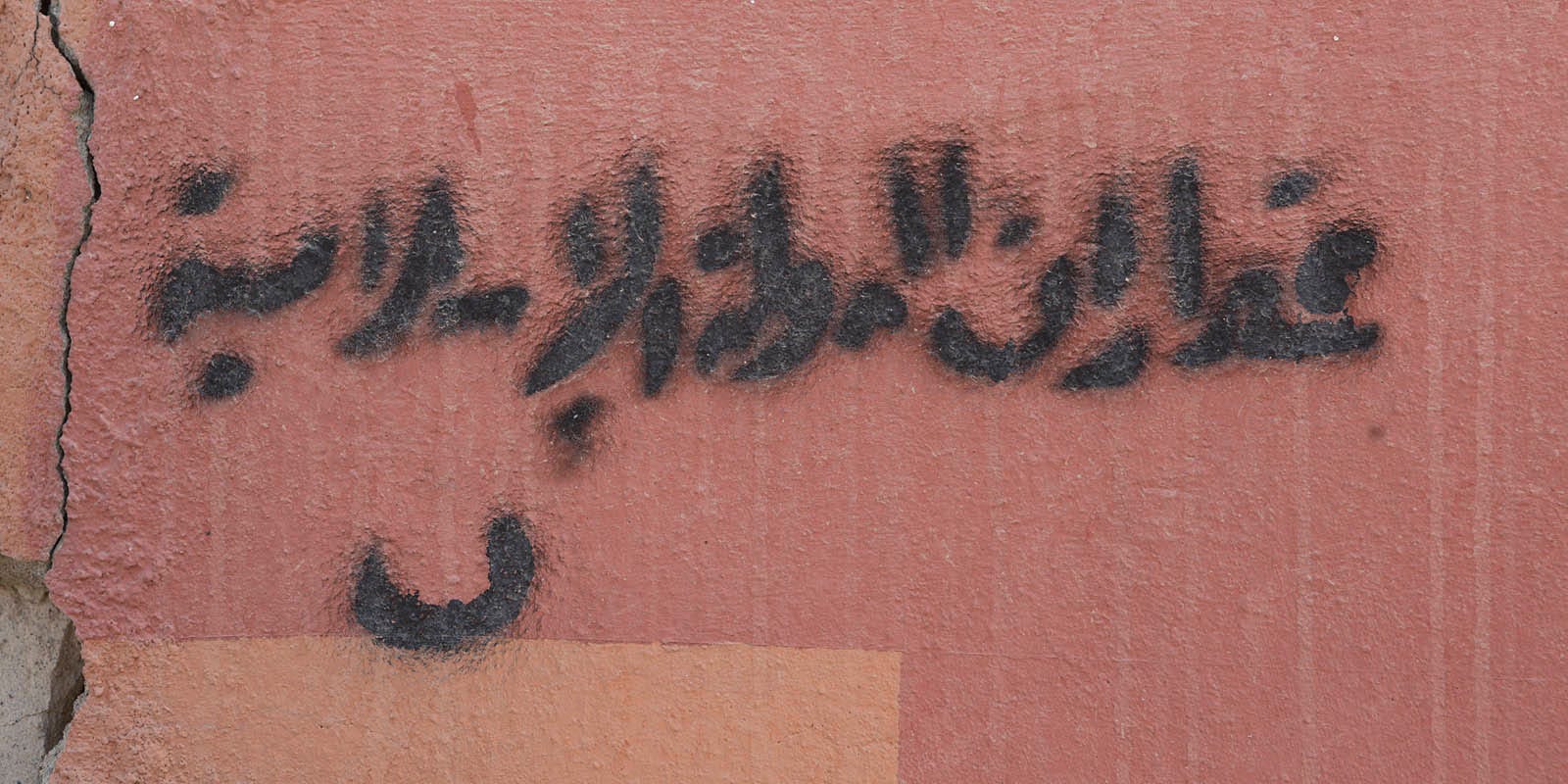

The Golden Brigade found that two years of Islamic State occupation were not kind to Bartella. Many streets are full of rubble and overgrown weeds. We see the occasional burned-out shop and a lot of militant graffiti.

Right now, the town is still a front line. Before residents can return and rebuild, someone will have to remove hundreds of improvised explosive devices and other dangerous ordnance the extremists left behind.

Beyond Bartella, in other parts of the Nineveh Governorate, the Iraqi Army and Kurdish Peshmerga have gradually retaken more ground from Islamic State. Christian and Assyrian militias contributed to some of the operations.

Many of these local troops escaped just before the extremists arrived. Some fled Mosul after militants demanded non-Muslims convert to Islam, pay a tax or suffer execution.

After seizing Bartella and other towns, Islamic State disparagingly branded non-Muslim homes with the Arabic letter nun. In some passages, the Koran refers to Christians as Nasarah, or inhabitants of Nazareth, the birthplace of Jesus Christ. The symbol is reminiscent of the Nazis marking Jews with a yellow Star of David.

During War Is Boring’s visit to Bartella, some of the Golden Brigade troops were resting, while others were still clearing portions of the town. Soldiers mentioned a militant appeared that morning, shot at their comrades and then disappeared.

Islamic State hid improvised bombs throughout Bartella. Trying to advance quickly toward Mosul, the Iraqi Army couldn’t stop to disarm all of the devices. Someone else will have to clear the rest out later.

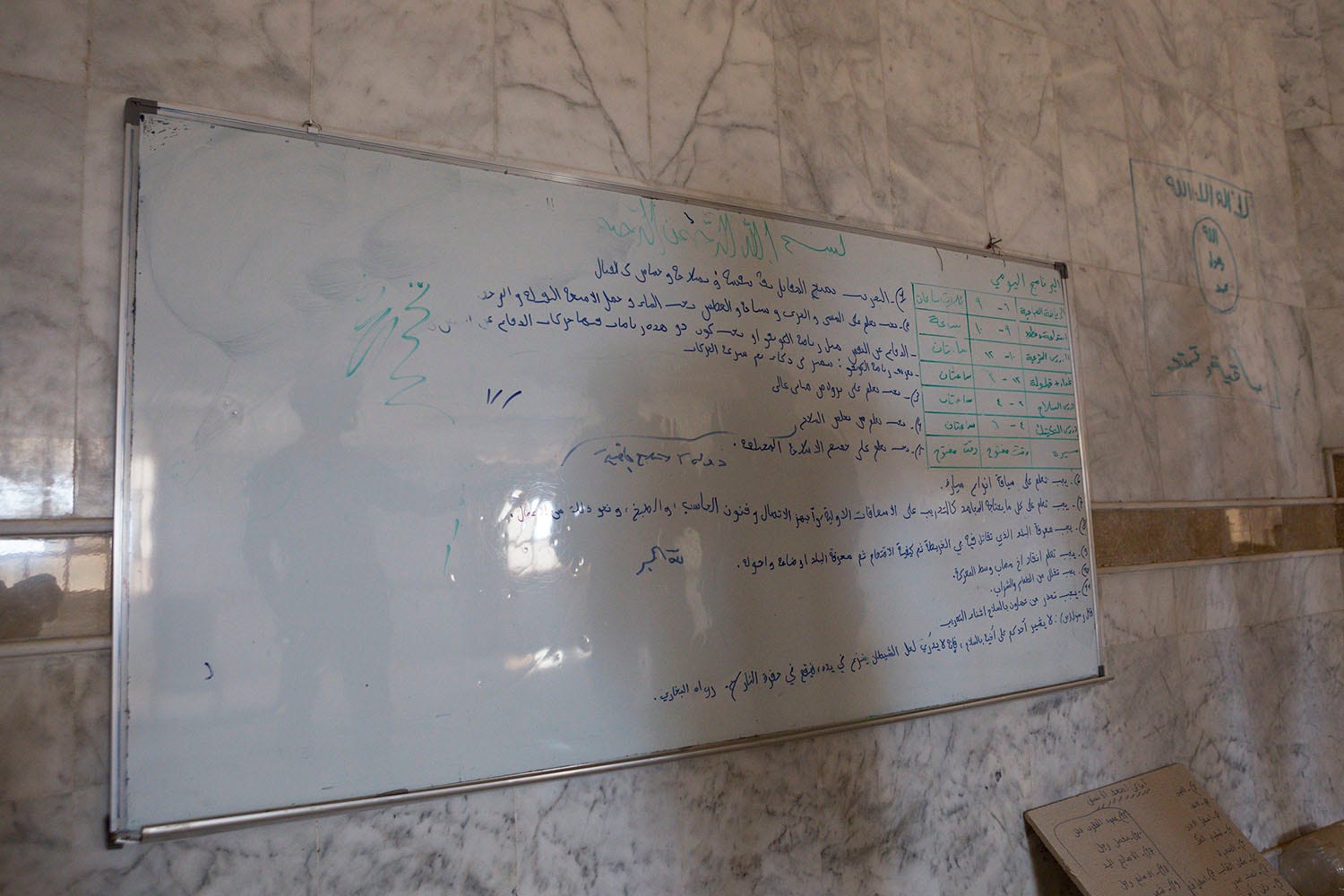

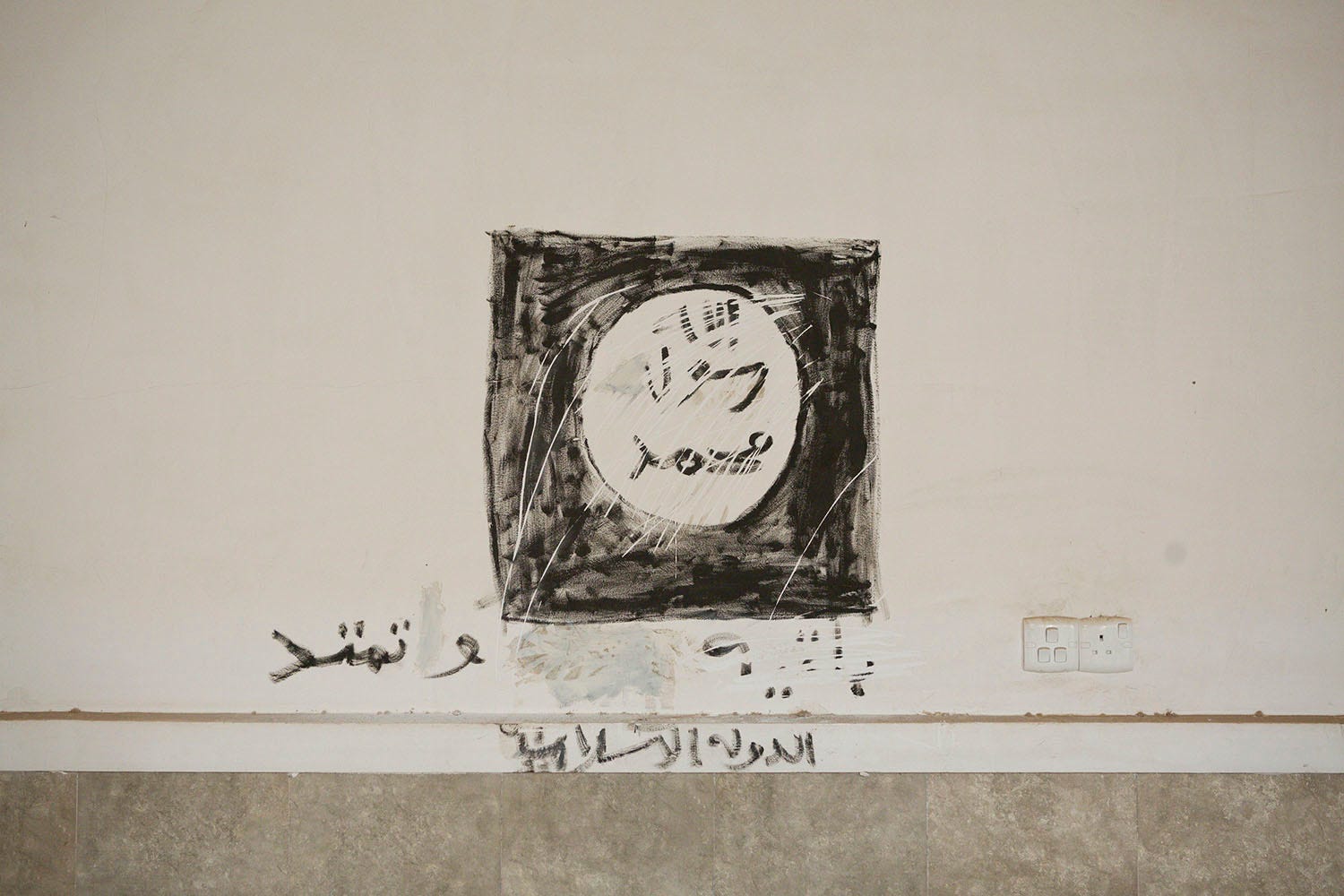

Although rigged with explosives, Islamic State left the Mart Shmony Church standing as the Golden Brigade approached Bartella. Despite the well-publicized demolition of churches in Mosul, the terrorists used this Christian house of worship for their own purposes.

While in control of Bartella, Islamic State fighters defaced numerous statues, murals and other depictions of non-Muslim figures. The extremist group claimed these icons were an affront to their puritanical, exclusionary beliefs.

The militants also smashed Christian gravestones and vandalized parts of the church.

The Iraqi Army’s fight for the town and the surrounding area was not easy. Although we don’t have official casualty figures, Golden Brigade soldiers mentioned comrades who died in the battle.

It’s hard to work out how much damage militants wrought on Bartella before the Iraqi Army arrived to liberate the town. In spite of the fighting, most houses seem intact.

Still, when we visited Bartella, the aftermath of battle was obvious. Pieces of clothing poked from under nearby rubble.

The remains of a body is in there somewhere, but no one is in a hurry to bury it. For now, the remains will mark the spot where the coalition hit its mark.

The smell in certain parts of town hints at more corpses hidden in the debris. When the front line has moved far enough beyond Bartella, troops will clear the bodies and bombs Islamic State abandoned in the city.

Only then will the town be ready for its displaced residents to return and begin again.

U.S. Military Blasts Islamic State’s Tunnels in Mosul

But getting at underground networks from the air is difficult

by JOSEPH TREVITHICK

WiB: On Oct. 17, 2016, Iraqi troops and Kurdish Peshmerga fighters — backed by American and other foreign forces — began to liberate Mosul and its surrounding environs from Islamic State. The offensive quickly uncovered extensive terrorist tunnels in the city.

The Pentagon responded by blasting the underground network for the sky.

“Many of you have seen and noted the enemy’s developed extensive tunneling networks in some of the areas that they use for tactical movement and to hide weapons,” U.S. Air Force Col. John Dorrian, a Pentagon spokesman, told reporters on Oct. 28, 2016.

In total, American strikes destroyed “46 of those tunnels since the liberation battle for Mosul started on October 17th, reducing the threat from a favored enemy tactic.”

However, despite decades of experience, destroying below-ground linkages from the air is still difficult, especially in areas full of innocent civilians. According to the U.S. Air Force, American planes didn’t drop any bunker busting bombs during these missions.

“The BLU-118, BLU-121 or BLU-122 warheads or the GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator have not been used in the Liberation of Mosul campaign,” Kiley Dougherty, the head of media operations for U.S. Air Force’s Central Command told War Is Boring by email. “ In fact, these weapons have not been used at all in support of Operation Inherent Resolve.”

Inherent Resolve is the Pentagon’s nickname for the campaign against Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

The Mosul operation is not the Pentagon’s first experience with tunnels. During the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong insurgents famously dug wide-ranging subterranean mazes throughout South Vietnam.

In the 1970s, North Korea dug at least four large tunnels under the Demilitarized Zone to sneak spies and commandos into the South. The top American command on the peninsula created a “tunnel neutralization team” to assess and seal the passages.

Underground bunkers and cave complexes were features in the first Gulf War in 1991, the intervention in Afghanistan in 2001 and the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Pentagon has taken note of Egyptian and Israeli efforts to stop Palestinian and other militants from digging under their borders.

In December 2001, the American commandos famously tried to flush out Osama Bin Laden and his cohorts from the Tora Bora caves near the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. Massive B-52 bombers pounded the mountains, but could only keep the terrorists hunkered down.

“Entire lines of defense were immolated by cascades of precisely directed 2,000-lb. bombs,” U.S. Army historians wrote in 2005. “But the depths of the caves and extremes of relief limited their effectiveness considerably.”

Air Force MC-130 special operations transports dropped 15,000 pound “Daisy Cutter” bombs, but couldn’t uproot the militants. The Al Qaeda leader eventually slipped across the border to settle near the Pakistani city of Abbottabad.

Within two years, the Pentagon had flown similar missions in Iraq. Despite the bombardment, on Dec. 13, 2003, a team of regular and elite U.S. troops found long-time Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein very much alive in a makeshift bunker outside the city of Tikrit.

By November 2015, tunnels again appeared as a factor in the fight against Islamic State. Faced with deadly American air strikes, the terrorists had literally gone to ground.

“In November 2015, when Kurdish forces entered Sinjar, Iraq, … they found that ISIL had adapted to air attacks by building a network of tunnels that connected houses,” U.S. Army analysts explained in a February 2016 report, using a common acronym for Islamic State.

“The sandbagged tunnels, about the height of a person, contained ammunition, prescription drugs, blankets, electrical wires leading to fans and lights, and other supplies.”

War Is Boring obtained this and other Army reviews of enemy tactics through the Freedom of Information Act.

But by the time the terrorist tunnels became an issue in Iraq and Syria, the U.S. Air Force had replaced the Vietnam-era Daisy Cutters. Instead, American crews had access to a number of newer specialized bombs.

Shortly after the Tora Bora debacle, American fliers received the first BLU-118s. Pentagon weaponeers cooked up the 2,000 pound thermobaric bombs specifically to blow up caves and tunnels.

Thermobaric warheads create massive, fireball-like explosions. If you can get one into a bunker or other confined space, the blast will bounce off the walls for an even more devastating effect.

In 2005, the Pentagon bought improved BLU-121s with a new delay fuze. This meant the bomb could bury itself deeper inside a tunnel before going off, causing maximum damage. Crews can fit both weapons with laser guidance kits for precise attacks.

And then there are bunker-busters such as the BLU-122 and GBU-57. These bombs have specialized features to break through reinforced sites, deep underground. Only the B-52 and B-2 bombers can carry the 30,000 pound Massive Ordnance Penetrator.

All of these weapons are great for attacking remote caves or isolated, underground military bases. They’re not necessarily good for attacking small tunnels in urban areas.

Even out in the open, fliers generally need powerful sensors or help from troops on the ground just to spot subterranean sites from the air. Though laser and GPS-guided bombs can strike within feet of a specific target, tunnel entrances might not be much larger than a person’s shoulders.

On top of that, in a densely packed city, any errant bombs have a greater chance of hitting unintended targets. A tunnel network under a house or apartment block presents a particularly problematic situation.

Add a thermobaric warhead to the mix and the results could be even more disastrous. There are reports Islamic State turned to human shields to ward off air strikes and Baghdad’s own thermobaric rocket launchers and artillery.

“We have seen many instances in the past where Daesh have used human shields in order to try and facilitate their escape,” Dorrian noted in his press conference. “Right now they’re using human shields to make the Iraqi Security Forces’ advance more difficult.”

The Pentagon would have run into similar hurdles when hitting the terror group’s tunnels in Mosul. By using conventional bombs, American crews might have had a harder time hitting the mark, but could better avoid unnecessary collateral damage. At the same time, this dynamic no doubt serves to reinforce the value of tunnel networks to the Islamic State.

And any assault on the group’s de facto Syrian capital in Raqqa will likely turn up more tunnels.

“Over time, adversaries of the U.S. and its allies have repeatedly shown that they are extremely adept at their use of this type of environment,” U.S. Army experts declared in a review of Hezbollah’s use of tunnels during Israel’s incursion into Lebanon in 2006.

“[This] consequently presents a situation in which, despite the U.S.’s technological superiorities, a threat could potentially gain an advantage over the U.S. and achieve victory.”

Thankfully, so far, Islamic State’s tunnels have only delayed Baghdad’s troops and their American partners.