The CIA’s Constitutional Crisis:

By John Prados and Arturo Jimenez-Bacardi

This electronic briefing book focuses on the experience of the Pike Committee in 1975. Formally known as the House Select Committee, and the forerunner of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence—the current oversight mechanism—the Pike Committee encountered the same CIA reluctance to endure investigation as the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) did during the more recent torture inquiry from 2009-2012. Indeed, at the time, Donald Gregg, a senior CIA officer who served as the agency’s top liaison person with Pike’s committee, recalled the experience as more difficult than some of his most hair-raising covert operations.[i] The Pike Committee’s investigation brought the Ford administration to the brink of a constitutional crisis over the principle that Congress had a right to investigate any aspect of Executive Branch activity. Pike also established a procedure—which congressional overseers typically neglect to make use of—for Congress to declassify information. Such procedures may prove crucial in the future.

The administration of Gerald R. Ford was far different from that of Donald J. Trump. So was the Congress in the two eras. Today’s Congress, although controlled by one party, is hampered by bitter political infighting. In 1975, Capitol Hill, though it was in the hands of the Democratic Party and coming off the Watergate affair, had a tradition of bipartisanship. President Ford faced congressional efforts to build mechanisms for dismantling what had come to be regarded as the “imperial presidency.”[ii] But Ford could enlist allies in Congress and reasonably hope to build consensus toward measures he considered desirable. Aspects of the intelligence crises of 1975, 2012-2014, and 2017-on, evolved with eerie similarity.

The Central Intelligence Agency’s problem at that time was, if anything, worse than in the Obama-Trump era, because there were parallel investigations of the agency by a presidential commission, the Senate, and Pike’s House of Representatives panel. Also, Otis Pike, the New York congressman chairing the HSC, moved fast to make up for lost time, because his HSC had ben reconstituted after a previous inquiry had failed to get off the ground. The CIA had tried to impose controls on all the investigations in the form of exacting agreements on the handling of classified information. To a large extent it had succeeded with the presidential commission (the Rockefeller Commission) and the Senate inquiry (the Church Committee), but the previous HSC had been derailed precisely because of the impression of collusion between the CIA and the committee. Pike was not about to fall into that trap.

Henry Kissinger and Otis Pike (undated photo).

Equally troubling, there were suspicions on both sides from the start. Director William E. Colby of the CIA thought Pike’s investigators a pick-up team who knew nothing, and the HSC principals a troop of publicity hounds. CIA officials were already on the defensive based on a number of damaging stories about them in the press in the course of 1975. Chairman Pike compounded CIA hostility by refusing to obligate his staff to sign CIA-like secrecy agreements, while opening a second front by declining to implement CIA-style compartmentation for storage of agency documents. Chairman Pike also rejected the formula later adopted under Ronald Reagan and used by subsequent administrations—including during George W. Bush’s presidency to shield CIA torture—of briefing only the committee chairman and vice-chair (which at higher levels translated into the “Gang of Four” or “Gang of Eight” groups). Robustly, Pike ruled that if the House of Representatives had wanted to create a two-person investigative committee it would have done so. Gaming the system was not permitted on his watch.

Responding to the House committee, Director Colby made CIA lawyer Mitchell Rogovin the point of contact for HSC requests to interview CIA officers, laid down access conditions to Pike, and informed CIA employees of both actions. When Pike rejected a letter from Rogovin, Colby and the lawyer then met with Pike, but that encounter turned into a confrontation. Rogovin believed Pike sought to avoid charges of having been coopted by the agency. Pike all but said as much when he responded to Colby’s follow up letter: “It’s a delight to receive two letters from you not stamped ‘Secret’ on every page …. You are concerned with the concept of ‘need to know’ and I am concerned with the concept of ‘right to know.’”[iii]

Pike held his first public hearing on August 4, 1975. He used the occasion to contrast the Ford administration’s public posture that it was cooperating fully with the CIA and White House’s actual practice of obfuscation and delay. The impasse escalated tensions, leading to destructive clashes between the sides. One prime example was the “briefcase episode.” Ford’s Office of Management and Budget had been refusing to hand over data regarding CIA’s budget, which Pike had requested from Colby on July 28. When White House lawyers Philip Buchen and Roderick Hills visited HSC offices to discuss the matter, Hills inadvertently left his briefcase behind with a secret document in it. Weeks later, Pike cited the incident as an example of how the Committee safeguarded classified information more carefully than the Ford administration. On September 3, White House staff secretary James E. Connor drew the battle lines within the administration over the Pike committee’s access to information by arguing that if President Ford failed to act a series of terrible consequences would follow (Document 3).

On September 10, with the administration pulling back on access, the Pike Committee subpoenaed documents for its next case study – of U.S. officials being caught by surprise by the 1968 Tet Offensive in Vietnam. The CIA was reluctant to comply. This is where our documentary exhibits pick up. It was at this point that the Ford White House escalated the dispute over access to information. On September 12, Assistant Attorney General Rex E. Lee, alleging Pike Committee leaks, terminated the Ford administration’s supply of information to the House committee (Document 4). The HSC threatened to go to court. Agency lawyer Rogovin failed to get Pike to modify his committee’s requests. Rogovin was then told the CIA had no authority to alter the deadline for it to respond to the subpoena.

Pike responded by returning just one item, using the opportunity to point out – in elaborate detail in a cover letter – that the “secret” classification had been unjustifiably imposed on inconsequential information (Document 10).

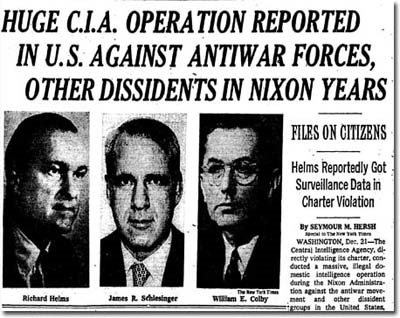

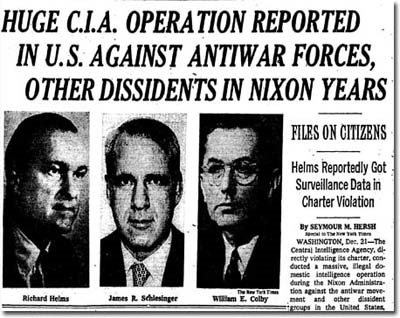

Seymour Hersh’s explosive revelations in The New York Times on December 22, 1974, led to White House and congressional investigations into the intelligence community, including establishment of the Pike Committee.

Seymour Hersh’s explosive revelations in The New York Times on December 22, 1974, led to White House and congressional investigations into the intelligence community, including establishment of the Pike Committee.

The demands for information, on the one side, and foot-dragging on the other, built to a crescendo that September. The HSC moved to hold a hearing to examine intelligence performance during the October War of 1973, and wanted to quote a paragraph from a CIA postmortem of this action. CIA tried once again to keep the material secret leading Pike to demand the material be released. Colby tried to shield a particular passage concerning intercepts of Egyptian radio communications, but Pike refused. When the HSC voted to release the material over CIA objections, that furnished Assistant Attorney General Rex Lee with his rationale for terminating cooperation (Document 4). The White House’s turn to the Department of Justice to enunciate its official position signaled the Pike Committee that President Ford’s patience had worn thin.

The CIA’s “Family Jewels” document collection triggered fresh hostility between the agency and the committee throughout this period. Colby showed Pike the full collection, but when HSC investigators wanted to see it, Langley supplied only a sanitized version. Upon renewed demand, Donald Gregg informed the HSC that top staff could review a different—also sanitized—version, but only at CIA headquarters. In November, fifteen minutes ahead of a press conference Pike had called to lambast CIA on this and other matters, the agency suddenly furnished a full copy.

Meanwhile, HSC investigators had discovered that, in a 1974 internal political crisis in Cyprus, U.S. diplomats had complained in State Department dissent channels that the Department’s favoritism toward Greece had worsened the situation. Pike’s staff wanted to look into this, too. Henry Kissinger, who simultaneously held the positions of national security adviser and secretary of state, not only demanded that nothing be given to Pike but insisted upon the return of all classified materials from the HSC. It is a measure of the falsity of many claims of national security damage caused by the release of classified information that Kissinger himself had already leaked the October war communications intelligence data that the Pike Committee was now to be punished for releasing. The leak had been to the writers Marvin and Bernard Kalb, who had written a biography of Kissinger.[iv] The “revelation” had already been public for a year. Scholar Frank J. Smist argues that the Pike declassification was a “phony issue” because the HSC’s wording was ambiguous and would have required the CIA to identify the offending text and explain how it was so damaging.[v]

By September 16, the CIA’s effort to control congressional access to records had had to be modified. Director Colby’s attempt to completely deny access to decision-making material collapsed amid the white heat of public controversy. Now the CIA and White House tried to apply different restrictions to HSC review of 40 Committee records (Document 8). The 40 Committee was the administration’s interagency unit that approved covert operations. Ford officials wanted to allow only cursory information to be reviewed, and to require that all examination of documentation take place at the White House, in NSC offices, with any notes retained at the NSC. (The Intelligence Community demanded similar restrictions during the 1987 Iran-Contra congressional hearings and the 2009 SSCI investigation of CIA torture programs.)

The White House scheme for a revised system to provide materials did not pass muster with the House Select Committee. Ford administration officials inexplicably resisted taking Pike Committee objections seriously until a White House liaison, meeting with ally Robert McCrory, senior Republican member of the HSC, noted that the committee fully intended to proceed in its own way – in other words, that GOP members would support the Democratic majority (Document 11). A letter from another Republican member to President Ford, affirming that committee members from both parties were united (Document13), made it plain the White House had little alternative.

In fact, neither Colby nor Ford had any running room. On September 20 it became clear the Pike Committee was preparing to sue the president (Document 14). Officials sought expert opinion. In a legal brief on September 22, the CIA’s own lawyers concluded that the HSC subpoena had been legally issued by an authorized body. The courts would accept that, the lawyers believed, and an “excellent chance” existed the judiciary would uphold the subpoena. Conversely, there was little probability a court would order a congressman or committee not to report on what he/they had investigated, or to avoid discussion of matters under their jurisdiction. Consequently, “there does not appear to be any realistic way in which the Agency can come out the winner” (Document 16). Colby and his lawyer, Rogovin, had sat through many meetings in the White House Situation Room at which officials had railed at congressional demands for information, only to have to yield the documents days or weeks later. Congress had a constitutional right to investigate, so the Ford administration was obliged to reply.

White House lawyers, reviewing these issues themselves, were only a little more optimistic, but they feared the courts would rely on the doctrine of “political issues” to avoid ruling on the very narrow grounds the lawyers saw open (Document 22). They, too, advised accommodation. Political adviser Max Friedersdorf predicted that “a serious confrontation is coming” (Document 20). Republican members of the Pike Committee warned the White House that both parties would unite to demand access, and that Pike was inclined to litigate, and to go as far as the Supreme Court to seek a judgment. The Ford White House and the CIA were on track for a white-hot constitutional crisis with the House Select Committee.

For his part, Henry Kissinger continued to advise President Ford to stand fast. The secretary of state held out for defying the congressional requests for documentation, and denying Congress had any role to play in releasing information (Document 21). Kissinger, in effect, was inviting the president to ignite a constitutional crisis, bringing the behind-the-scenes dispute over access into the open. The main impact of Kissinger’s stand, had he succeeded, would have been to widen the constitutional breach by suppressing the release of information on the Cyprus crisis and October War. This was information Congress had a right to ask for, and it amounted to substituting the secretary’s personal objectives for the U.S. government’s overall interests.

On September 24, a decision document went to President Ford, who approved a compromise that effectively overrode Kissinger’s objections. The compromise provided that, if the Pike Committee agreed to White House conditions, it would immediately receive the information it sought, excepting categories such as intelligence sources and methods. The documents would be considered to be on loan to the HSC. If Congress wished to release (declassify) information and an agency objected, the administration would have a chance to make its case for secrecy and, if that were rejected, the president would make the final decision. White House and CIA officials deliberated over new rules for documents to be provided to the Pike Committee. If Pike rejected the compromise offer, Ford agreed to adopt a “maximum control” standfast position (Document 25).

The HSC, facing an approaching deadline to complete its inquiry, could hardly afford a lengthy controversy. Pike agreed to Ford’s formula. On September 29, the two met in the Oval Office along with the senior House leadership to consecrate the new arrangement. Secretary Kissinger opted out (the documents do not explain why Ford permitted him to do so) , and sought to keep State Department materials from HSC hands. The committee later issued a separate subpoena against him, resulting in an eventual agreement to allow State Department officials to create a substitute document containing the gist of the documents the HSC had requested.

Meanwhile, following the September compromise, the CIA had gained confidence in its ability to preserve secrecy. Director Colby’s agency adopted the device of “lending” its documents to the House Select Committee as a means of asserting that only the agency could “declassify,” or release the information. By October 3, the CIA had provided 80 documents requested. One remained pending. Some 188 lines had been blanked out. Another 100 items had come from the Defense Intelligence Agency. In the end, CIA secret documents, alone some 90,000 pages, filled 32 file cabinets in the HSC offices (Document 34).

The last act revolved around the Pike Committee’s actual report. It remains unclear when, exactly, President Ford got the idea of quashing the document by inducing the full House of Representatives to refuse to release it, but it was very possibly linked with the September compromise. Or it could have happened in connection with a very embarrassing development for Ford on November 20, when the HSC’s Senate counterpart, the Church Committee, refused to suppress its investigation of CIA assassination plotting, and released its conclusions to the public. That provided a discomfiting precedent for the Pike report, which the White House certainly wished to avoid. On the other hand, the HSC was continuing its foraging among secret records with fresh subpoenas issued in November, looking toward a January 31, 1976, deadline.

On January 15, Ford wrote Pike that he had determined that publication of the HSC Report would be detrimental to national security. When Pike persisted, Ford insisted on January 29 that outstanding disputes over classified information had to be submitted to the Executive for its determination. That forced Pike to seek an extension for printing the report, which the House Rules Committee granted only on the condition that the White House approve release of the report. Ford relied upon Pike’s September compromise to claim the committee’s report itself was a classified document and thus subject to White House approval. Pike failed to convince the House to overrule that condition and the president duly rejected release of the report.[vi] Suddenly, on February 16, 1976, large excerpts of the Pike Report appeared in the newspaper The Village Voice, to which it had leaked. Journalist Daniel Schorr was the acknowledged recipient of the leak. The text that appeared, in discussing the Ford administration’s practices in furnishing classified material, included the passage, “when legal proceedings were not in the offing, the access experience was frequently one of foot-dragging, stone-walling, and careful deception.”[vii]

When the House of Representatives created its Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) on July 14, 1977, the struggle over the congressional power to declassify information was reflected in House Rule XLVIII, Section 7, which acknowledges the HPSCI’s power to “disclose publicly any information in [its] possession.” Specifically, the rule provided that the Select Committee may vote to release classified information. It would notify the president in cases where secrets had been furnished by the Executive. If there were no objections, after five days the information could be declassified. If there were, the president would be required to submit them “personally, in writing.” In that case the HPSCI could either take no action, leaving the information classified; or it could vote to send the dispute to the House floor with a recommendation for consideration. The full House of Representatives would then determine the outcome. The procedure specified an ability to consider such matters in secret session, set a maximum time for debate, and made an explicit promise that HPSCI would not reveal properly classified information except under this procedure.

The legacy of Otis Pike and his committee was thus not only to promote intelligence oversight in general, but also to establish an explicit mechanism for the House of Representatives to declassify secret documents. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence has available to it a similar provision under Section 8 of Senate Resolution 400, which brought the committee itself into existence.[viii] These congressional rules were careful to delineate that the Executive’s ability to prevent congressional declassification of information was limited to documents which Executive agencies, such as the CIA, had provided to Congress. The White House has no power to limit the release of classified information originated in Congress itself. Except for the courtesy which Congress has chosen from time to time to extend the Executive in these matters, several presidents would have sustained deeper political wounds from congressional investigations.[ix]

NYTimes

NYTimes.jpg)

FoxLatino

FoxLatino

Seymour Hersh’s explosive revelations in The New York Times on December 22, 1974, led to White House and congressional investigations into the intelligence community, including establishment of the Pike Committee.

Seymour Hersh’s explosive revelations in The New York Times on December 22, 1974, led to White House and congressional investigations into the intelligence community, including establishment of the Pike Committee.