Gotta wonder if Jane Fonda had her own entire file cabinet. Hollywood did have many names included on the blacklist. A pamphlet titled ‘red channels’ included the names. For how this blacklist worked due to the FBI and HUAC, go here.

Ralph David Abernathy, Donald Sutherland, Women’s Liberation, and Vietnam Veterans Against the War – Among Those on NSA’s Watch List

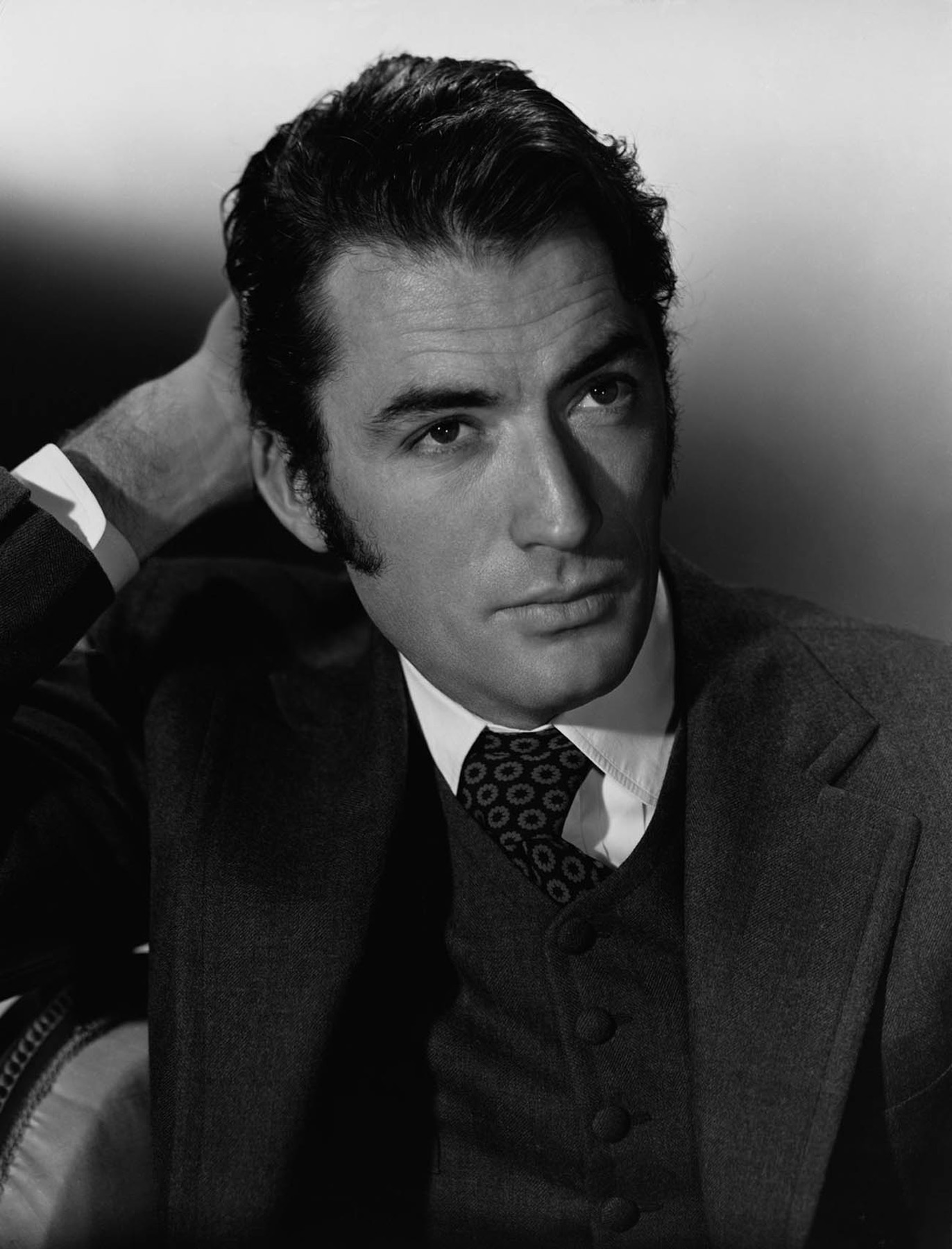

NSA Biographic Files Included 73,000 U.S. Citizens, Including Journalists Art Buchwald and Tom Wicker and Actors Joanne Woodward and Gregory Peck

Washington, D.C., September 25, 2017 – The National Security Agency’s (NSA) own official history conflated two different constitutionally “questionable practices” involving surveillance of U.S. citizens, according to recent NSA declassifications published today by the National Security Archive, an independent research organization based at The George Washington University. During the mid-1970s, the U.S. Senate’s Church Committee investigated a number of such “practices” by NSA, including the so-called Watch List program, which monitored the international communications of anti-Vietnam war activists and other alleged “subversives.” The “Watch List” was one of the questionable activities; the other was the NSA’s creation of a voluminous filing system on prominent U.S. citizens whose names appeared in Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) collected by the Agency. That filing system, abandoned in the early 1970s and destroyed in 1973, stayed secret for years.[1]

The files on well-known Americans were a product of the Agency’s sweeping efforts to track the communications of Cold War adversaries and to identify the individuals mentioned in them. Ultimately the filing system, and corresponding indexes, surpassed 1,000,000 names, including 73,000 U.S. citizens mentioned in SIGINT collected by the Agency. Among them were politicians, corporate leaders, trade unionists, Hollywood personalities, and journalists, ranging from Church Committee member Senator Walter Mondale (D-MN) and actor Joanne Woodward to IBM CEO Thomas Watson and United Auto Workers President Leonard Woodcock.

The recent NSA release has more information on the Watch List, such as the identities of a number of targeted individuals and organizations: Canadian actor and antiwar activist Donald Sutherland, civil rights leader Ralph David Abernathy, journalist Seymour Hersh, antiwar activist David Dellinger, the Venceremos Brigade, and an entire social movement, Women’s Liberation.

Four years ago, the National Security Archive published a newly declassified National Security Agency history that included details about the Agency’s Watch List. As it turned out, the Agency’s history mistakenly folded in the NSA’s filing system on U.S. citizens into the Watch List, which focused on social reformers, revolutionaries, anti-war activists, and their organizations. Thus, the history incorrectly stated that Senator Howard Baker and journalists Art Buchwald and Tom Wicker, among others, were on the Watch List. Declassified documents confirm, however, that the NSA included those individuals and 73,000 others as part of the Agency’s name files of U.S. citizens. New documents that the NSA released to the Archive through a mandatory declassification review appeal provide an important corrective to the Agency’s official history by demonstrating that the Watch List and the biographical files were what the Church Committee – the U.S. Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, chaired by Senator Frank Church (D-ID) – saw as two different “questionable practices” with respect to the Agency’s treatment of U.S. citizens.

To identify people mentioned in intercepted messages and other SIGINT products, the NSA (and its predecessors) created special indexes and sets of biographical files. The index to the biographical files was the “Rhyming Dictionary” used by NSA analysts as they decrypted and reported on SIGINT. Eventually including over a million names, the “Rhyming Dictionary” was organized in forward and reverse alphabetical order to make it easier for intelligence analysts to access the names of individuals and to retrieve biographical files as needed. When the Agency began to collect the names of U.S. personalities during the 1960s, it included them in the “Rhyming Dictionary” and created corresponding files that ended up filling 8-10 filing cabinets with over 73,000 entries.

According to the newly declassified documents, among the subjects of biographical files were prominent U.S. individuals. Besides Joanne Woodward, Thomas Watson, and Walter Mondale, the files included Washington Post humorist Art Buchwald, Federal Reserve Board Chairman Arthur Burns, actor Gregory Peck, Congressman Otis Pike (D-NY), New York Times columnist Tom Wicker, civil rights leader Whitney Young, and members of the Senate Select Committee including Howard Baker, Jr., and Frank Church. The Church Committee regarded the creation of files on American citizens by a U.S. intelligence agency as an improper activity, but their specific existence was not disclosed at the time, even though the procedures that generated such files were discussed during hearings.

The NSA’s Watch List, the other dubious activity, had been created in the early 1960s to keep track of U.S. citizens traveling to Cuba. During the following years Watch List targets broadened. After President Kennedy’s assassination, it included possible threats to the president.[2] On 20 October 1967, the Watch List began including anti-Vietnam War and civil rights activists, after U.S. Army intelligence informed the Agency “that Army ACSI, assistant chief of staff for intelligence [General William P. Yarborough], had been designated executive agent by DOD for civil disturbance matters and requested any available information on foreign influence over, or control of, civil disturbances in the U.S.” That comported with the thinking of President Lyndon Johnson who privately claimed that covert financial support from “international Communism” was behind the anti-Vietnam War movement, which was then preparing for a major demonstration in Washington (21 October 1967).[3] To determine whether there were such connections, the Federal Bureau of Investigation began providing hundreds of names for the Agency’s Watch List. During the Nixon administration, the list expanded further to include narcotics traffickers and terrorist organizations.

According to testimony by NSA Director General Lew Allen, in October 1975, U.S. government agencies nominated the names of individuals and organizations that appeared on the Watch List. Thus, to cover the Defense Intelligence Agency’s “requirements on possible foreign control of, or influence on, U.S. antiwar activity,” DIA nominated the names of 20 U.S. persons who traveled to North Vietnam. The FBI “submitted watch lists covering their requirements on foreign ties and support to certain U.S. persons and groups,” with the lists including “names of ‘so-called’ extremist persons and groups … active in civil disturbances, and terrorists.” The FBI lists included about 1,000 individuals. The Secret Service nominated about 180 U.S. individuals and groups that “were potentially a threat to Secret Service protectees.” During 1967-1973, Allen testified, all of the lists combined had a “cumulative total of about 450 U.S. names on the narcotics list, and about 1,200 U.S. names on all other lists.”

Senator Church and his colleagues did not object to Watch Lists of narcotics traffickers or to genuine threats to the president, but they wondered about the “lack of adequate legal basis for some of this activity and what that leads to.” Allen agreed that there was a problem and spoke of “domestic intercepts which cannot be conducted under the President’s constitutional authority for foreign intelligence,” which meant that “we are not authorized by law or constitutional authority and they are clearly prohibited.” As General Allen explained, there were “interpretations which deal with the right to privacy [from] unreasonable search and seizure of the fourth amendment.” It was “self-doubt” (referred to in Document 10) that led the NSA to stop accepting Watch Lists with the names of U.S. citizens in the summer of 1973. When Attorney General Elliot Richardson raised questions about the propriety of FBI and Secret Service requests for information from NSA Allen officially closed down the program.

One of the most sensational revelations of the Church Committee was Operation SHAMROCK by which the major telecommunications companies RCA, Western Union, and International Telephone and Telegraph reluctantly shared their telegram traffic with the NSA and its predecessors from 1945 to the early 1970s. Near the program’s end, NSA analysts were reviewing 150,000 telegrams a month. Information from the telegrams provided grist for the Watch List, which, in the words of Frank Church, “resulted in the invasion of privacy of American citizens whose private and personal telegrams were intercepted.” Church also saw a betrayal of trust by companies whose “paying customers who had a right to expect that the messages would be handled confidentially.” In November 1975 those and other considerations led Church and the committee majority to unilaterally declassify facts about the SHAMROCK program over the objections of President Ford. According to former Committee staffer L. Brit Snider, “This was the “only occasion … where a Congressional committee voted to override a presidential objection and publish information the President contended was classified.”[4]

A mandatory declassification review request by the National Security Archive to the National Security Agency produced the documents in today’s posting. The subject of the request was the sources cited in an endnote to the NSA history. The documents in the Agency’s initial release were excised and more information on the watch list and the Rhyming Encyclopedia was released under appeal. Pending declassification requests to the FBI and other agencies may produce more information on the history of the Watch List.

To read the documents, go here.

Gregory Peck

Gregory Peck  Joanne Woodward

Joanne Woodward