The Russian campaign — taking advantage of Facebook’s ability to simultaneously send contrary messages to different groups of users based on their political and demographic characteristics — also sought to sow discord among religious groups. Other ads highlighted support for Democrat Hillary Clinton among Muslim women.

These targeted messages, along with others that have surfaced in recent days, highlight the sophistication of an influence campaign slickly crafted to mimic and infiltrate U.S. political discourse while also seeking to heighten tensions between groups already wary of one another.

The nature and detail of these ads has troubled investigators at Facebook, on Capitol Hill and at the U.S. Justice Department, say people familiar with the advertisements who spoke on the condition of anonymity to share matters still under investigation.

The House and Senate Intelligence committees plan to begin reviewing the Facebook ads in coming weeks as they attempt to untangle the operation and other matters related to Russia’s bid to help elect Trump in 2016.

“Their aim was to sow chaos,” said Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., vice-chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee. “In many cases, it was more about voter suppression rather than increasing turnout.”

The top Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, Rep. Adam Schiff of California, said he hoped the public would be able to review the ad campaign.

“I think the American people should see a representative sample of these ads to see how cynical the Russian were using these ads to sow division within our society,” he said, noting that he had not yet seen the ads but had been briefed on them, including the ones mentioning “things like Black Lives Matter.”

The ads which Facebook found raise troubling questions for a social networking and advertising platform that reaches two billion people each month and offer a rare window into how Russian operatives carried out their information operations during an especially tumultuous period in U.S. politics.

Investigators at Facebook discovered the Russian ads in recent weeks, the company has said, after months of trying in vain to trace disinformation efforts back to Russia. The company has said it had identified at least $100,000 in ads purchased through 470 phony Facebook pages and accounts. Facebook has said this spending represented a tiny fraction of the political advertising on the platform for the 2016 campaign.

The previously-undisclosed ads suggest that Russian operatives worked off of evolving lists of racial, religious, political and economic themes. They used these to create pages, write posts and craft ads that would appear in user’s news feeds — with the apparent goal of appealing to one audience and alienating another. In some cases, the pages even tried to organize events.

“The idea of using Facebook to incite anti-black hatred and anti-Muslim prejudice and fear while provoking extremism is an old tactic. It’s not unique to the United States and it’s a global phenomenon,” said Malkia Cyril, a Black Lives Matter activist in Oakland, California. and the executive director for the Center for Media Justice. Social media companies “have a mandate to standup and take deep responsibility for how their platforms are being abused.”

Facebook declined to comment on the contents of the ads being turned over to congressional investigators, and pointed to a Sept. 6 statement by Alex Stamos, the company’s chief security officer, who noted that the vast majority of the ads run by the 470 pages and accounts did not specifically reference the U.S. presidential election, voting or any particular candidate.

“Rather, the ads and accounts appeared to focus on amplifying divisive social and political messages across the idealogical spectrum — touching on topics from LGBT matters to race issues to immigration to gun rights,” Stamos said at the time.

Moscow’s interest in U.S. race relations date back decades.

In Soviet times, operatives didn’t have the option of using the Internet, so they spread their messages by taking out ads in newspapers, posting fliers and organizing meetings.

Much like the online ads discovered by Facebook, messages spread by Soviet-era operatives were meant to look as though they were written by bonafide political activists in the United States, thereby disguising the involvement of an adversarial foreign power.

Russian information operations didn’t end with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

After a lull in tensions, Russia’s spy agencies became more assertive under the leadership of President Vladimir Putin. In recent years, those services have updated their propaganda protocols to take advantage of new technologies and the proliferation of social media platforms.

“Is it a goal of the Kremlin to encourage discord in American society? The answer to that is yes,” said former U.S. ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul, director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University. “More generally, Putin has an idea that our society is imperfect, that our democracy is not better than his, so to see us in conflict on big social issues is in the Kremlin’s interests.”

Clinton Watts, part of a research team that was among the first to warn publicly of the Russian propaganda campaign during the 2016 election, said that identifying and exploiting existing social and cultural divisions are common Russian disinformation tactics dating back to the Cold War.

“We have seen them operating on both sides” said Watts, a fellow with the Foreign Policy Research Institute and a former FBI agent.

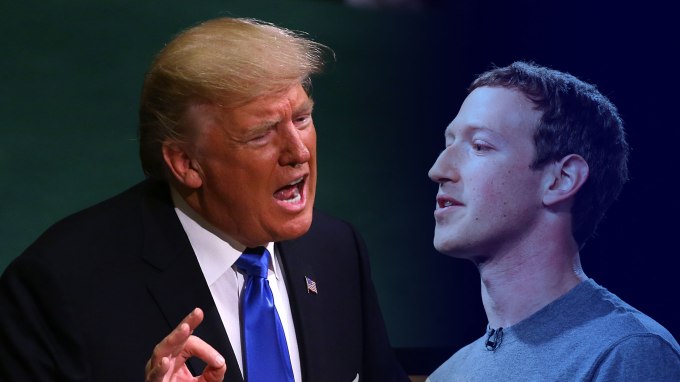

When Mark Zuckerberg founded Facebook in his college dorm room in 2004, no one could have anticipated the company would become an advertising juggernaut worth almost half a trillion dollars — the largest online advertising company in the world after Google. Roughly a third of the world’s population now log in monthly.

As Facebook’s user base rapidly expanded, it wrote the playbook for digital targeting in the smartphone era — and for the type of micro-targeting that has become critical to modern political campaigns.

The social network invested heavily in building highly-sophisticated automated advertising tools that could target specific groups of people who had expressed their preferences and interests on Facebook, from newlyweds who studied at Dartmouth College to hockey enthusiasts living in a particular zip code in Michigan.

The migration from traditional personal computers to smartphones and tablets also helped Facebook gain a major edge: The company pioneered techniques to help advertisers reach the same user on their desktop and mobile devices, leading Facebook to grow seven-fold in its value since it went public in 2012. Today, advertisers who want to target Facebook users by demographics or interests have tens of thousands of categories to choose from, and they are able to flood users with ads wherever they go on the Internet.

Unlike most websites, where ads appear alongside content, ads on Facebook have directly appeared in people’s newsfeeds since 2012. If users like a page, the administrators of that page can pay for ads and post content that will then appear in the cascade of information from publishers and friends that users see right away when they log onto Facebook.

Since the 2012 presidential election, Facebook has become an essential tool for political campaigns that wish to target potential voters. During the height of election season, political campaigns are among the largest advertisers on Facebook. Facebook has built a large sales staff of account executives, some of whom have backgrounds in politics, that are especially trained to assist campaigns in spreading their messages, increasing engagement, and getting immediate feedback on how they are performing.

The Trump campaign used these tools to great effect, while Clinton’s campaign preferred to rely on its own social media experts, according to people familiar with the campaigns.

Since taking office, Putin has on occasion sought to spotlight racial tensions in the United States as a means of shaping perceptions of American society.

Putin injected himself in 2014 into the race debate after protests broke out in Ferguson, Missouri, over the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, an African-American, by a police officer who was white.

“Do you believe that everything is perfect now from the point of view of democracy in the United States?” Putin told CBS’ 60 Minutes. “If everything was perfect, there wouldn’t be the problem of Ferguson. There would be no abuse by the police. But our task is to see all these problems and respond properly.”

In addition to the ads described to The Post, Russian operatives used Facebook to promote anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim messages. Facebook has said that one-quarter of the ads bought by the Russian operatives identified so far were targeted to a particular geographic area.

While Facebook has downplayed the impact of the Russian ads on the election, Dennis Yu, chief technology officer for BlitzMetrics, a digital marketing company that focuses on Facebook ads, said that $100,000 worth of Facebook ads could have been viewed hundreds of millions of times.

“$100,000 worth of very concentrated posts is very, very powerful,” he said. “When you have a really hot post, you often get this viral multiplier. So when you buy this one ad impression, you can get an extra 20- to 40-times multiplier because those people comment and share it.”

Watts, the Foreign Policy Research Institute fellow, has not seen the Facebook ads promised to Congress, but he and his team saw similar tactics playing out on Twitter and other platforms during the campaign.

Watts said such efforts were most likely to have been effective in mid-Western swing states such as Wisconsin and Michigan, where Democratic primary rival Sen. Bernie Sanders had beaten Clinton. Watts said the disinformation pushed by the Russians includes messages designed to reinforce the idea that Sanders had been mistreated by the Democratic Party and that his supporters shouldn’t bother to vote during the general election in November.

“They were designed around hitting these fracture points, so they could see how they resonate and assess their effectiveness,” Watts said. “I call it reconnaissance by social media.”

p

p

photo courtesy CBS

photo courtesy CBS