First…there is no policy as admitted in a Senate Intelligence Hearing of the heads of the intelligence agencies and confirmed by Senator Angus King (Maine).

CTIIC is the federal lead for intelligence support in response to significant cyber incidents, working—on behalf of the IC—to integrate analysis of threat trends and events, build situational awareness, and support interagency efforts to develop options for degrading or mitigating adversary threat capabilities.

The idea of creating a cyber threat framework came from observations among the US policy community that cyber was being described by different agencies in a variety of ways that made consistent understanding difficult. There are over a dozen analytic models being used across government, academia, and the private sector. Each model reflects the priorities and interests of its developer, but the wide disparities across models made it difficult to facilitate efficient situational analysis that was based on objective data.

The framework will be scalable and facilitate data sharing at “machine speed.” Implementation within the USG will include processes to reduce or eliminate double-counting of threat data.

- Cyber Threat Framework Frequently Asked Questions

- A Common Threat Framework Food for Thought

- Cyber Threat Framework – Overview

- Cyber Threat Framework – How to Use Lesson Plan

- Cyber Threat Framework – Lexicon

- A Common Cyber Threat Framework: A Foundation for Communication

- A Common Cyber Threat Framework: A Foundation for Communication – Short Version

Attackers exploited the CVE-2017-5638 Apache Struts vulnerability. The vulnerability affects the Jakarta Multipart parser upload function in Apache and could be exploited by an attacker to make a maliciously crafted request to an Apache web server.

The vulnerability was fixed back in March, but the company did not update its systems, the thesis was also reported by an Apache spokeswoman to the Reuters agency.

Compromised records include names, social security numbers, birth dates, home addresses, credit-score dispute forms, and for some users also the credit card numbers and driver license numbers.

Now experts argue the Equifax hack is worse than previously thought, according to documents provided by Equifax to the US Senate Banking Committee the attackers also stole taxpayer identification numbers, phone numbers, email addresses, and credit card expiry dates belonging to some Equifax customers.

This means that crooks have all necessary data to arrange any king of fraud by steal victims’ identities. More here.

Further, the Trump administration appears to omitted any reference to the Chinese cyber threat domestically….here is a clue on their activity and how they cannot be trusted…and we have not even mentioned Russia..

In 2012 Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE were considered high threat risks to the United States and sadly, both were introduced again at this same Senate hearing on February 13, 2018.

China’s government has denied reports that it spied on the servers at the African Union’s Chinese-built headquarters for more than five years, gaining access to confidential information.

In an investigation published by French newspaper Le Monde, China, which also paid and built the computer network at the AU, allegedly inserted a backdoor (in French) that allowed it to transfer data. The hack wasn’t detected until Jan. 2017 when technicians noticed that between midnight and 2 am every night, there was a peak in data usage even though the building was empty. After investigating, it was found that the continental organization’s confidential data was being copied on to servers in Shanghai.

China’s ambassador to the AU dismissed the reports as “absurd” and “preposterous.” Kuang Weilin told reporters in Ethiopia that it was “very difficult to understand” Le Monde’s claims and that the story was certain to “create problems for China-Africa relations.”

The revelations come as African presidents convene in Addis Ababa to attend the continental summit on governance. In 2012, when the AU building was completed, it was signified as a symbolic gesture aimed at solidifying Sino-Africa relations. The landmark 20-story office tower overlooking a pearl-shaped conference center was “a gift” from the Chinese government to help African nations integrate better and improve their institutional capacity.

But the alleged data theft puts a spin on that rosy affair and might strain the relationship between the two sides. China is heavily involved in Africa, with its companies and entrepreneurs conducting trade and investing heavily in African countries. Chinese aid has also been blamed for propping up authoritarian regimes, constructing shoddy roads and infrastructure built by imported Chinese workers, and focusing mainly on countries home to oil, minerals, and other resources that China needs. But China is also cultivating the next generation of African leaders, with Beijing taking thousands of African leaders, bureaucrats, students, and business people to China for training and education. More here.

For sure there is no policy and lawmakers are dumbfounded on introducing any kind of offensive or consequential legislation. Hello Angus?

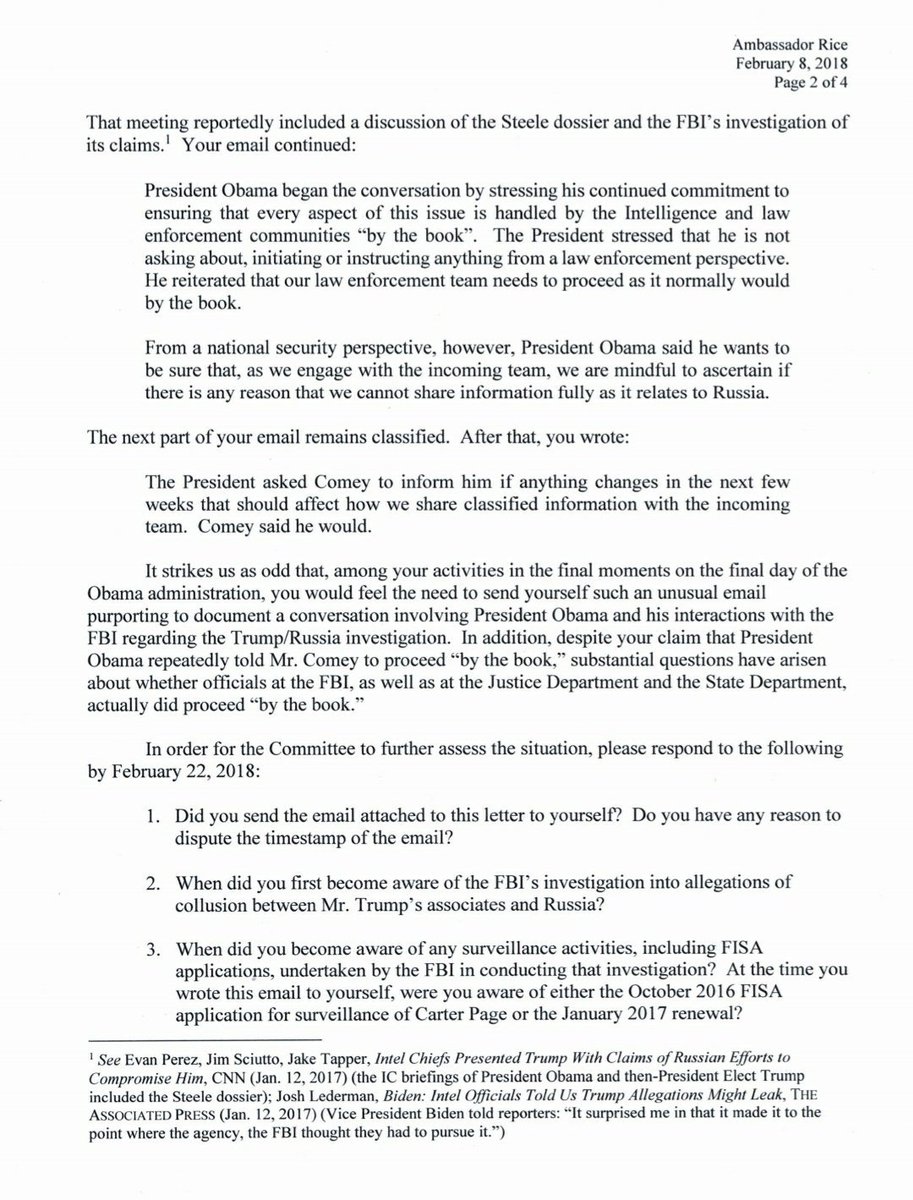

Questions are what about the unmasking and who did she blind copy in the email? What were Obama’s ultimate requests and demands for cover-ups? Okay…read on.

Questions are what about the unmasking and who did she blind copy in the email? What were Obama’s ultimate requests and demands for cover-ups? Okay…read on.