While reading the long and factual summary below on the 9/11 hijackers, ask yourself the following questions:

Note the date of this summary, 2010

- Have immigration policies changed today?

- Are there new systems in place?

- Do members of Congress still standing with the 9/11 Commission Report?

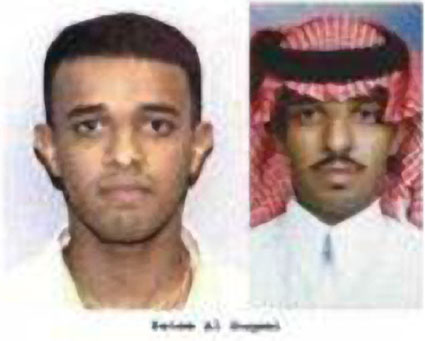

The Complete Immigration Story of 9/11 Hijacker Satam al Suqami

This Memorandum is in memory of Danny Lewin, whose incredible life was ended by hijacker Satam al Suqami on American Airlines Flight 11 prior to its tragic crash into the North Tower of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.

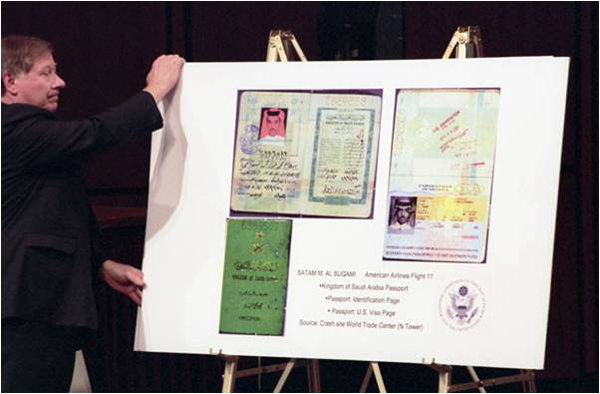

I dedicate this Memorandum to my former colleague on the September 11 Commission, Walt Hempel, who gave me confidence that our investigation was as accurate and as thorough as possible. The collating of the digital images you find here was due primarily to his work.

The past year and a half has provided a litany of examples, some tragic, that America is not safe from terrorist conspiracies and acts. Our processing and informational analysis has improved greatly since September 11 at our air and land ports of entry, but our southwest border is suffering from a near national security crisis due to Mexican narco-insurgency. Meanwhile, aviation security remains subject to incomplete vetting procedures and issues of international cooperation. What is becoming increasingly clear is that despite some real gains in border and aviation security, we are not safe. Thus, the value of continuing to learn from the terrorist travel story of September 11 remains relevant today as we continue to rummage through panoplies of choices about immigration and border security. If any immigration issue should rise above the fray and remain a standalone, it should be border security. This Memorandum is an attempt to help inform that debate more fully, by providing never-before seen digital images that back up previously published material in the September 11 border team’s monograph, 9/11 and Terrorist Travel.

Background. In January 2009, the National Archives made available some of the 9/11 Commission work product that revealed to the public for the first time much of the evidence that resulted in the 9/11 Commission Report published (as required by law) in July 2004. Among those archives was some of the most precious work the border team had uncovered after numerous and arduous document requests to the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), the State Department, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation: hard copies or digital images of travel documents of the hijackers.

In 9/11 and Terrorist Travel, my team and I were able to include images of about one-quarter of the physical evidence we had accumulated that aided fact development and recommendations for both the 9/11 Final Report and 9/11 and Terrorist Travel, which was written to provide substantive support for the 9/11 Final Report recommendations. But the remainder of those images has remained buried these past years.

As the ensuing five years have passed since the publication of the 9/11 Commission materials, one hijacker in particular stands out for a number of reasons – not only for the tragic story of his likely murder of Daniel Lewin on American Airlines Flight 11 before the crash – but also because he was the only hijacker (of two total) well aware that he was an illegal overstay on September 11. We know this because this hijacker had attempted to enter the Bahamas in May 2001 in order to re-enter the United States and obtain a six-month length of stay like his “muscle” co-conspirators (i.e., those who were not the pilots). He was also the only such hijacker that had only received a business traveler one-month length of stay upon entry. He failed, and thus was the only hijacker not to use his travel documents to obtain a state-issued driver’s license or ID, causing him again to be one of the few hijackers who we know used his passport for check-in on the morning of September 11, rather than a U.S.-issued ID card. In addition, because we did not – and still do not—have an Exit system in place that logs visitors out of the country, authorities were initially confused as to whether or not he was even in the United States on September 11. Both these issues – illegal overstays and failure to implement an Exit system – remain outstanding issues in the United States, affecting the national discussion of immigration and border security. The goal this story is to better inform that discussion.

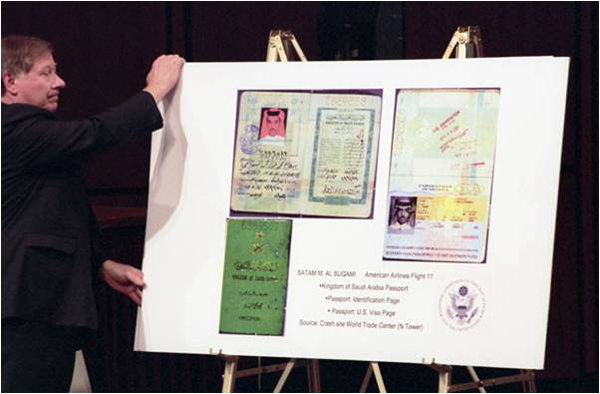

Below is a consolidation of the 9/11 and Terrorist Travel facts, verbatim, about Satam al Suqami as developed by myself as immigration counsel and my colleague, Tom Eldridge, who conducted the visa analysis. Supporting our work are the digital images of Suqami’s passport culled from reams of materials, mostly done by Walt Hempel. One small miracle in our investigation was learning that Suqami’s passport survived the attack; having its images to review helped solidify findings.

I have not changed our words, but added in the heretofore unseen images alongside source information of Suqami’s travel documents, providing more depth to 9/11 Commission final work products and reiterating the basic message that our borders matter to national security. Detecting a terrorist through his travel documents and records, coordinated with intelligence – and today with biometrics and programs that assure we know who is entering and exiting our country – is equally important to economic and national security. This story of Suqami reiterates that point.

On September 11, Daniel Lewin was on board American Airlines Flight 11 from Boston to Los Angeles, which crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center. However, Lewin was likely murdered prior to the crash by 9/11 hijacker Satam al Suqami. Two months before his death, Lewin was named as one the 100 most important people in the national information industry. He was survived by his wife and two sons.

Daniel Lewin, 31, a mathematician and entrepreneur, co-founded and ran Akamai Technologies, nearly becoming a billionaire in the dot-com stock boom. At the time of his death, he was a PhD candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was said to have become a paper-billionaire when Akamai stock first became available. Lewin was born in Denver and raised in Jerusalem, where he served in Sayeret Matkal, a counter-terrorism unit of the Israeli Defense Forces. He had previously worked for IBM’s research lab in Haifa, Israel.

The FAA memo’s summary of the Flight 11 shooting incident, real or not, is the most detailed and specific – not to mention shocking – of the four hijacking summaries. It says Lewin, sitting in seat 9B, was “shot by passenger Satam al-Suqami,” sitting behind him in seat 10B. (Both names match those on the manifest released by the airline.) However, we do not know if he was shot or stabbed; the on-flight phone call between flight attendant Betty Ann Ong and the FAA states that Ong relayed that Lewin, sitting in seat 9B, was killed by the passenger in seat 10B at approximately 8:20. That passenger in 10B was later identified as Satam M. A. Al Suqami.

— Walt Hempel, professional staff member, 9/11 Commission

The 9/11 hijackers and conspirators on American Airlines Flight 11 – North Tower of the World Trade Center were: Mohamed Atta Hijacker (Pilot), Abdul Aziz al Omari, Waleed al Shehri, Wail al Shehri, and Satam al Suqami.

Introduction: Factual Overview of the September 11 Border Story

Entering the United States as tourists was important to the hijackers, since immigration regulations automatically guaranteed tourists six months of stay. Thus the 14 muscle hijackers who entered the United States in the spring and early summer of 2001 were able to remain in the country legally through September 11. The six-month tourist stays also assured the hijackers of sufficient time to make such preparations for their operation as obtaining the identification some of them used to board the planes on September 11.

Fourteen of 15 operatives and all of the pilots acquired one or multiple forms of U.S. state-issued identification. Only Satam al Suqami did not, possibly because he was the only hijacker who knew he was out of immigration status: His length of stay end date of May 20, 2000, was clearly inserted in his passport.

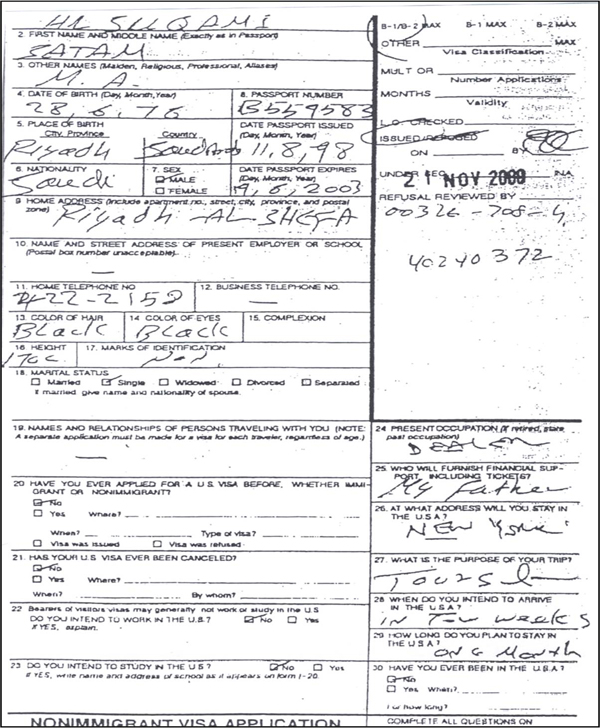

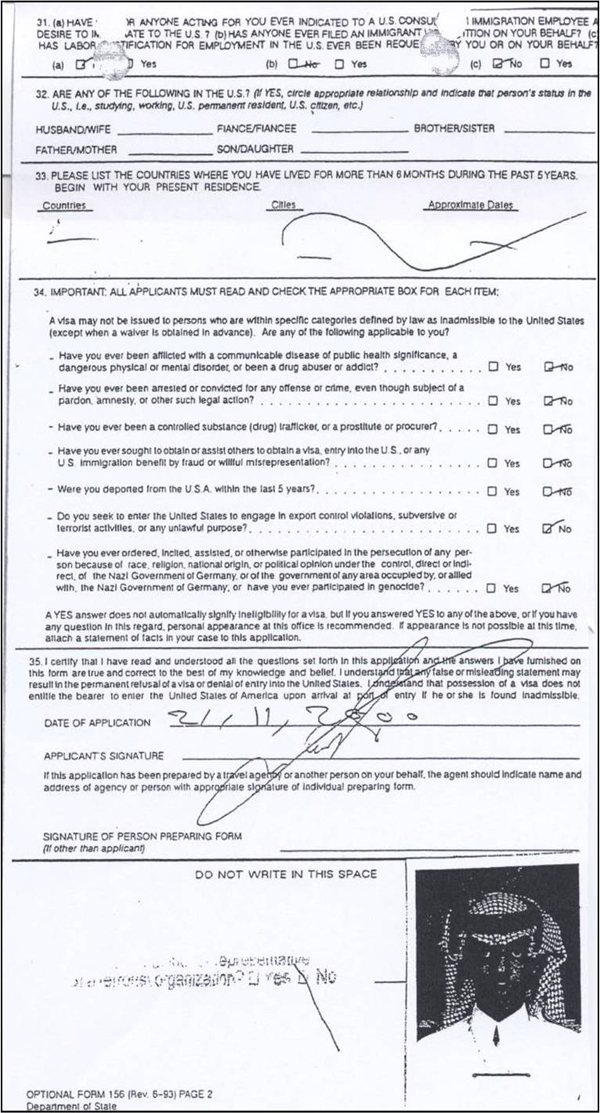

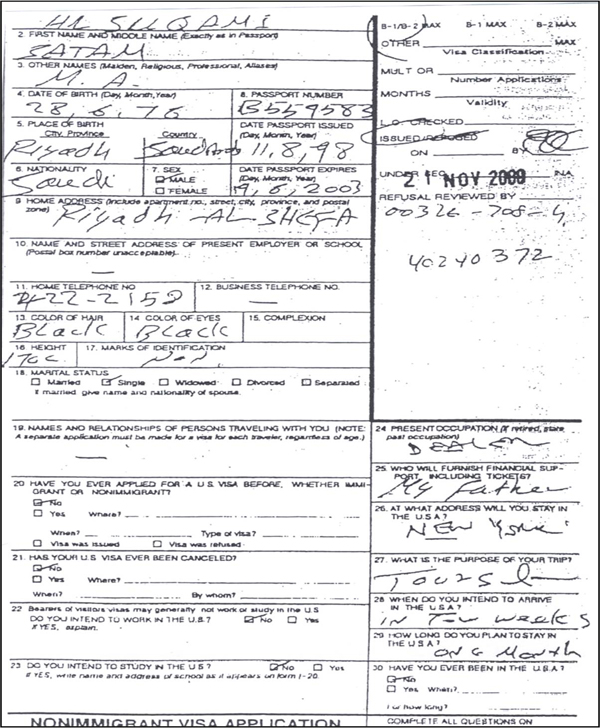

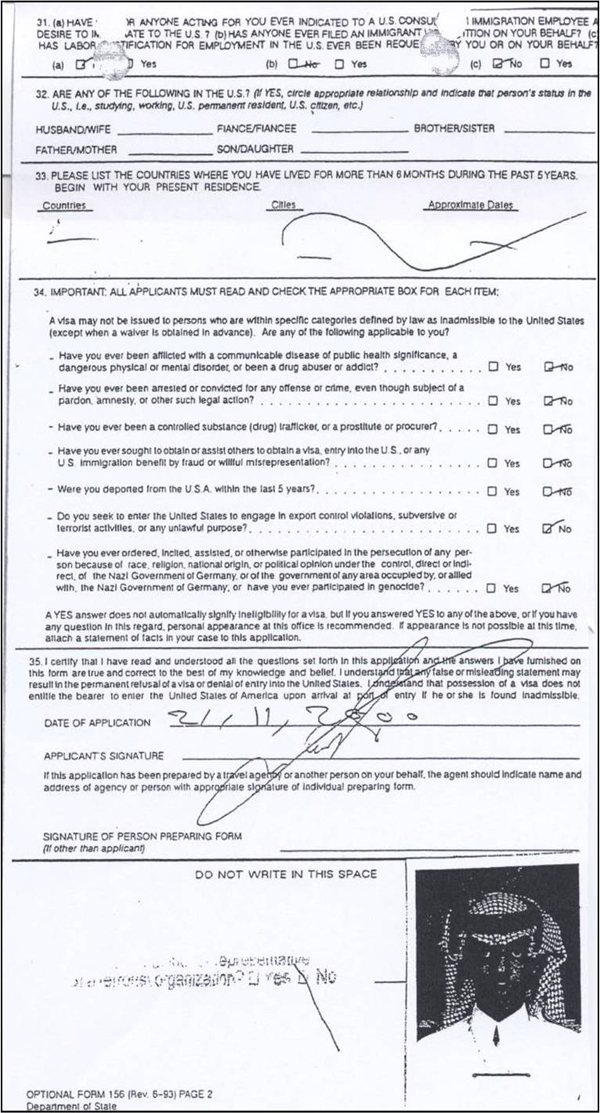

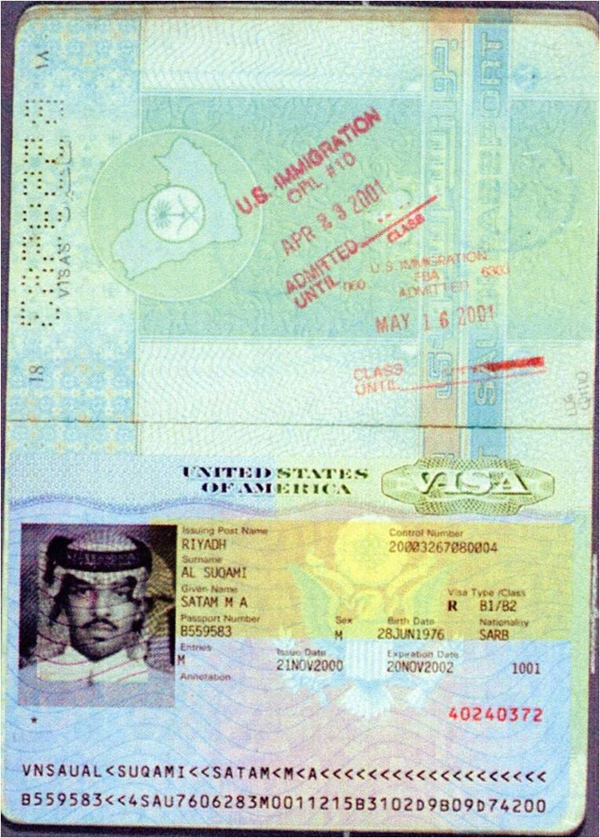

November 21, 2000. State Department records show that Satam al Suqami, a Saudi, applied for and received a two-year B-1/B-2 (tourist/business) visa in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. There is strong evidence that the passport Suqami submitted with this application had fraudulent travel stamps now associated with al Qaeda. These stamps remain classified, and are not contained here.

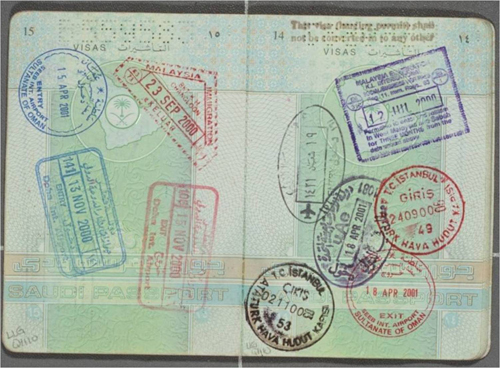

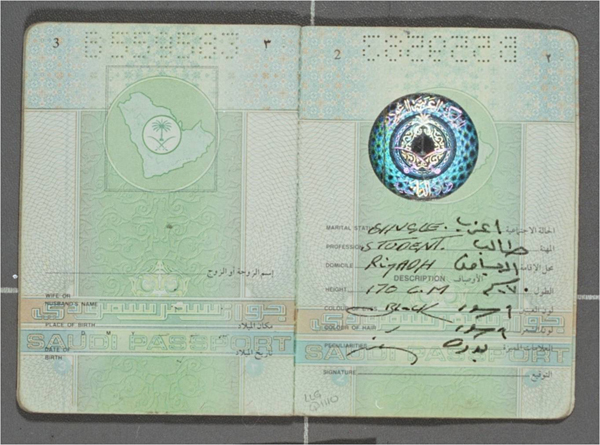

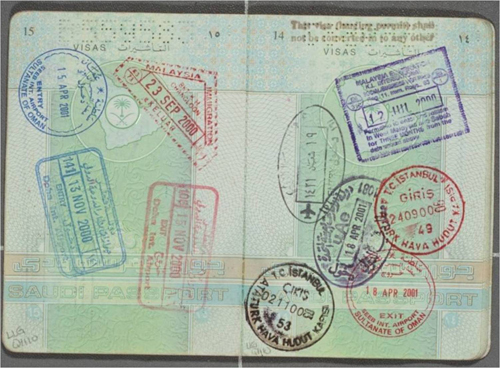

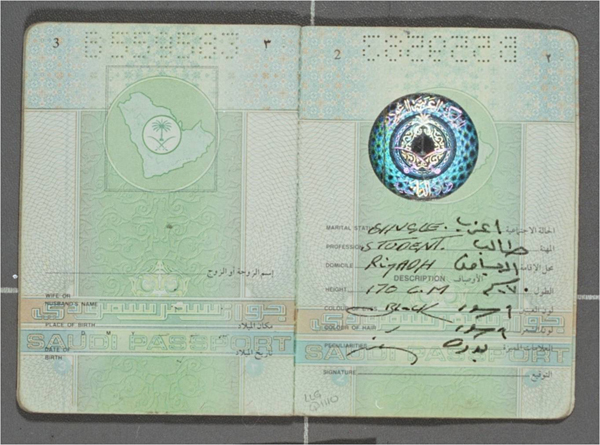

Suqami’s Saudi Arabian passport with numerous travel stamps, some of which were determined to be fraudulent. They include multiple travel to Instanbul, Malaysia, Oman, and Egypt. There are no travel stamps from Pakistan, Afghanistan, or Iran, all three locations likely destinations.

Although Suqami had false travel stamps in his passport as of 9/11, we do not know if these stamps were placed in his passport before or after submission of his visa application, although the dates on some of the false stamps pre-date the date he applied for his visa.

Suqami left blank the line on which he was asked to supply the name and street address of his present employer.

Suqami’s visa application. The stamp with the “No” crossed states: “Are you a member or representative of a terrorist organization?”

The consular officer who issued the visa said he interviewed Suqami because he described his present occupation as “dealer,” the word Saudis often put on their applications when they meant “businessman.” The officer testified that he asked Suqami a number of questions, including, he believes, who was paying for the trip. Although the officer stated that notes were always taken during interviews, none were written on Suqami’s application, raising the possibility that the officer’s memory of having conducted an interview was false. In any case, Suqami evidently raised no suspicions and his application was approved.

April 23, 2001. According to INS records, Waleed al Shehri and Satam al Suqami, both Saudis, entered together at Orlando from Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Suqami was the only Saudi muscle hijacker admitted on business, and only for one month. Both were admitted by the same primary immigration inspector.

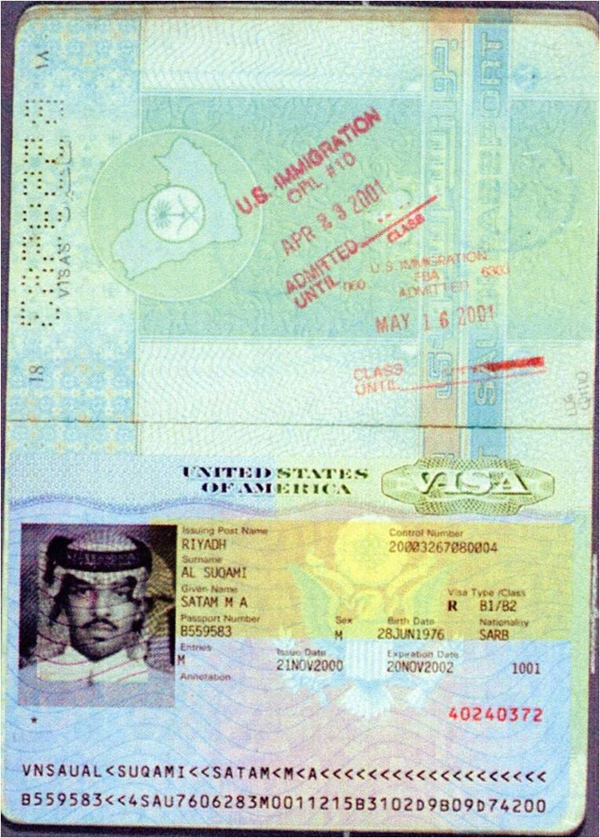

Above is Suqami’s U.S. visa issued on November 21, 2000. The Final Report states that Satam al Suqami and Mojed Moqed flew from Iran to Bahrain in late November 2000, in all likelihood as soon as the plotters were assured that Suqami had obtained his U.S. visa, critical to al Qaeda for entry into the United States. Also note on page 18 a U.S. entry on April 23, 2001, and re-entry on May 16, 2001, after the failed attempt to enter the Bahamas.

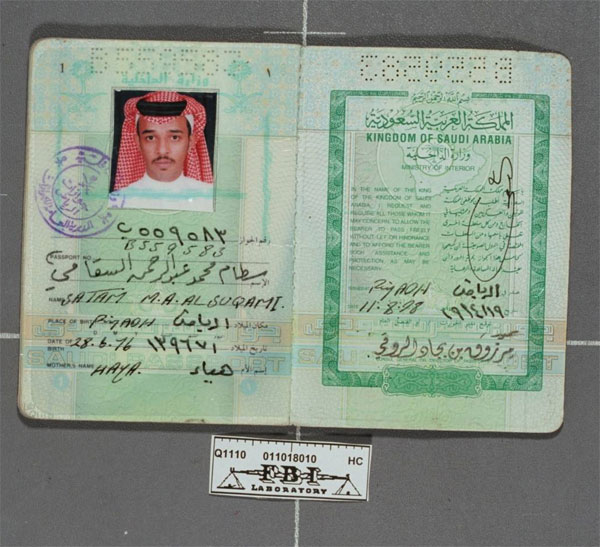

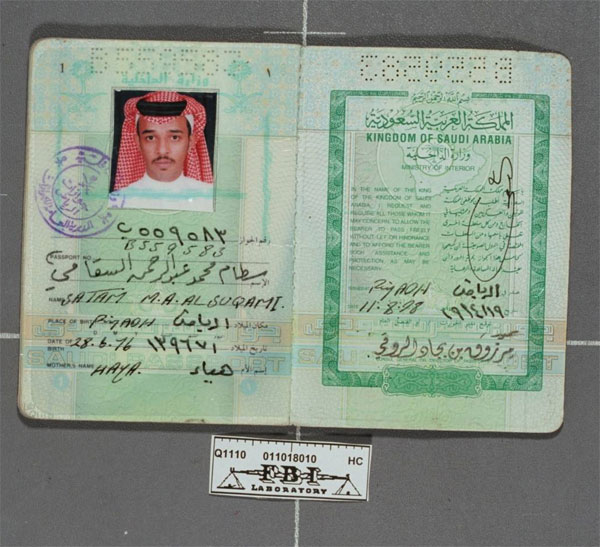

Biographic pages of Suqami’s passport

FBI reports revealed that Suqami’s passport was recovered by NYPD Detective Yuk H. Chin from a male passerby in a business suit, about 30 years old. The passerby left before being identified, while debris was falling from WTC 2. The tower collapsed shortly thereafter. The detective then gave the passport to the FBI on 9/11. Later analysis showed that it contained what are now believed to be fraudulent travel stamps associated with al Qaeda. In addition, the forensic document analysis of Satam al Suqami’s passport indicates that on page 8, “An Arabic stamp impression located near the top of page 8 has been partially covered with correction fluid,” as stated in an INS letter from John Ross, INS Supervisory Forensic Document Examiner, to Lorie Gottesman, FBI Document Examiner, on November 2, 2001.

Correction fluid on top right stamp, indicating fraudulent travel stamps

Upon reviewing color copies of the document, the inspector who admitted Suqami told the Commission he did not note any such fraud. Indeed, he could not have been expected to identify the fraud at the time of Suqami’s admission – it was not discovered by the intelligence community until after the attacks.

May 16, 2001. Waleed al Shehri and Suqami again traveled together, this time out of the country to the Bahamas, where they reserved three nights at the Bahamas Princess Resort. INS records show that they turned in their arrival record, which was now acting as an exit record, boarded the plane, and arrived in Freeport. Ramzi Binalshibh, a key facilitator and organizer for the 9/11 conspiracy who was denied a U.S. visa, stated during interrogations that the trip was intended to extend Suqami’s legal length of stay in the United States.

Bahamian immigration refused the two entry, however, because neither had a Bahamian visa. They therefore had to return to their starting point, in this case Fort Lauderdale. Because they never entered the Bahamas, under U.S. immigration law they had never left the United States. After being refused entry by the Bahamian INS at Freeport, they were sent through U.S. “pre-clearance” before boarding the plane back to Miami. By making possible immigration inspections of U.S.-bound travelers prior to their arrival, pre-clearance helped ease the burden of admission at busy U.S. airports. These stations also prevented travelers deemed inadmissible from boarding U.S.-bound planes. Pre-clearance stations existed prior to September 11 in Canada, Ireland, the Bahamas, and the Caribbean. In this pre-clearance process, immigration waived them through but customs stopped Shehri. The inspection lasted one minute; Shehri was not personally searched, nor was his luggage x-rayed. Customs records showed they boarded a plane and returned to Miami.

The attempted three-day jaunt by Shehri and Suqami to the Bahamas would cause difficulty for the INS in assisting the FBI’s investigation into 9/11 since the INS records indicated the two had left the United States and not returned. This is because when the two left Miami for the Bahamas, they handed in their I-94 departure records as required. When they were turned around in the Bahamas for a lack of visas, under U.S. immigration law they never left the United States. However, they were not given new arrival records when they physically returned to the United States. Therefore, when the attacks occurred, investigators thought that Suqmai and Shehri had departed the United States, which is what the INS records indicated.

May 20, 2001. Suqami joined the millions of overstays in the United States after failing to file for an extension of stay with the INS after he returned from the Bahamas. Had he been allowed into the Bahamas, upon his return to the United States he would have likely been granted an additional length of stay in the country as a tourist. As it was, he remained in illegal status until September 11.

September 11. As the hijackers boarded four flights, American Airlines Flights 11 and 77, and United Airlines Flights 93 and 175, at least six used U.S. identification documents acquired in the previous months, three of which were fraudulently obtained in northern Virginia. Airline check-in personnel remembered that Suqami, the only hijacker who did not have a state-issued identification, used his Saudi passport as check-in identification for American Airlines Flight 11.

An Entry-Exit System. The INS also was unable to enforce the rules regarding the terms of admission of visitors to the United States because there was no national tracking system designed to match a person’s entry with that person’s exit. Inspectors were similarly unaware of whether a visitor had overstayed a previous visit.

In 1996, expressing frustration at the apparent number of overstays in the United States and the inability of INS to enforce the law, Congress took action. It passed a law requiring the attorney general to develop an automated entry-exit program to collect records on every arriving and departing visitor. Congress provided about $40 million over four years to fund the development of such a system. By contrast, Congress provided nearly $1 billion to increase the Border Patrol’s presence in the southwest in order to stem the flow of illegal immigration from Mexico. Countering terrorist entry was not a rationale for the system.

Leaders of border communities along the Canadian and Mexican borders, where more than a million people move back and forth daily, denounced the system. They argued that it would inhibit border trade. Some members of Congress, along with senior INS managers, agreed and decided to automate only the entry process. Prior to September 11, even these efforts were unsuccessful. Thus, while the hijackers were preparing for the planes operation in the United States, immigration authorities had no way to determine whether any of them had overstayed their visas or traveled in and out of the country. The lack of an entry-exit system was especially significant for Satam al Suqami and Nawaf al Hazmi, as both were illegal overstays.

(In June 2010, CIS held a symposium of high-level officials and policy thinkers on the issue of implementing an Exit control. A report can be found at http://cis.org/exit-panel.)

The Immigration and Naturalization Service Overview

A review of the entries and immigration benefits sought by the hijackers paints a picture of conspirators who put the ability to exploit U.S. border security while not raising suspicion about their terrorist activities high on their operational priorities. Evidence indicates that Mohamed Atta, the September 11 ringleader, was acutely aware of his immigration status, tried to remain in the United States legally, and aggressively pursued enhanced immigration status for himself and others.

Despite their careful efforts to understand and operate within the legal requirements, however, the hijackers were not always “clean and legal.” For example, they used fraudulent documents and alias names as necessary. And when the hijackers could, they skirted the requirements of immigration law. Ziad Jarrah, for example, failed to apply to change his immigration status from tourist to student, and Satam al Suqami failed to leave the country when his length of stay expired. They thus were vulnerable to exclusion at ports of entry and susceptible to immigration law enforcement action. In this section, we explore how the hijackers succeeded in making it through U.S. airports of entry in 33 of 34 attempts, drawing on interviews of the immigration and customs inspectors who had contact with the hijackers, immigration law, port of entry policy, training, and resources available to inspectors in primary and secondary inspections.

The four pilots, who went in to and out of the United States 17 times, were admitted on business four times. Only one muscle hijacker, Suqami, was given a one-month stay as a business traveler when he entered at Orlando on April 23, 2001, with Waleed al Shehri. Both hijackers had filled out their Customs declarations stating that they intended a 20-day stay. The immigration arrival record did not require information about the length of stay, however; and since immigration inspectors checked the Customs declarations only for completeness and not for substance, the 20-day stay request was ignored – to their advantage, in fact.

Indeed, the 30-year INS veteran inspector who admitted both hijackers told the Commission that the Customs declaration had no bearing on the length of stay he gave Suqami, which was based solely on Suqami’s answer regarding the purpose of his visit. That Suqami was limited to a business instead of a tourist stay meant that he and Nawaf al Hazmi (who overstayed his tourist visa despite filing for an extension of his stay in July 2000) were the only operatives who had overstayed their authorized lengths of stay as of September 11. The four pilots, who went into and out of the United States 17 times, were admitted on business four times. Only one muscle hijacker, Suqami, was given a one-month stay as a business traveler when he entered at Orlando on April 23, 2001, with Waleed al Shehri.

Immigration Violations Committed by the Hijackers in the United States

Once a non-U.S. citizen is admitted to the United States, he or she remains subject to U.S. immigration laws and may be deported if any are violated. The hijackers violated many laws while gaining entry to, or remaining in, the United States. Here are the violations pertaining to Suqami:

- Every hijacker submitted a visa application falsely stating that he was not seeking to enter the United States to engage in terrorism. This was a felony, punishable under 18 U.S.C. § 1546 by 25 years in prison and under 18 U.S.C. § 1001 by 5 years in prison, and was a violation of immigration law rendering each one inadmissible under 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(6)(c).

- The hijackers, when they presented themselves at U.S. ports of entry, were terrorists trained in Afghan camps who had prepared for and planned terrorist activity to further the aims of a terrorist organization – al Qaeda – making every hijacker inadmissible to enter the United States under 8 U.S.C.§ 1182(a)(3)(b).

- At least two (Satam al Suqami and Abdul Aziz al Omari) and possibly as many as seven of the hijackers (Suqami, Omari, Mohand al Shehri, Hamza and Saeed al Ghamdi, Ahmed al Nami, and Ahmad al Haznawi) presented to State Department consular officers passports manipulated in a fraudulent manner, a felony punishable under 18 U.S.C. § 1543 by 25 years in prison and a violation of immigration law rendering them inadmissible under 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(6)(c).

- At least two hijackers (Suqami and Omari) and as many as 11 of the hijackers (Suqami; Omari; Waleed, Wail, and Mohand al Shehri; Hani Hanjour; Majed Moqed; Nawaf al Hazmi; Haznawi; and Hamza and Ahmed al Ghamdi) presented to INS inspectors at ports of entry passports manipulated in a fraudulent manner, a felony punishable under 18 U.S.C. § 1543 by 25 years in prison and a violation of immigration law rendering them inadmissible under 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(6)(c).

- Nawaf al Hazmi and Suqami overstayed the terms of their admission, a violation of immigration laws rendering them both deportable under 8 U.S.C. § 1227(a)(1)(B).

Walt Hempel

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States

Commission hearing January 26, 2004

Senate Office Building

REUTERS/Rick Wilking US Secretary of State John Kerry, left, with Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif before a meeting in Geneva in January.

REUTERS/Rick Wilking US Secretary of State John Kerry, left, with Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif before a meeting in Geneva in January. ReutersMahmoud Ahmadinejad, left, then Iran’s president, with his Venezuelan counterpart Hugo Chavez at Miraflores Palace in Caracas in 2012.

ReutersMahmoud Ahmadinejad, left, then Iran’s president, with his Venezuelan counterpart Hugo Chavez at Miraflores Palace in Caracas in 2012. Tehran, Iran.

Tehran, Iran. ReutersKirchner with defense minister Nilda Garre, right, during a meeting with Chavez at the Casa Rosada Presidential Palace in Buenos Aires in 2009.

ReutersKirchner with defense minister Nilda Garre, right, during a meeting with Chavez at the Casa Rosada Presidential Palace in Buenos Aires in 2009.