Low risk and high profits…

From Interpol in part:

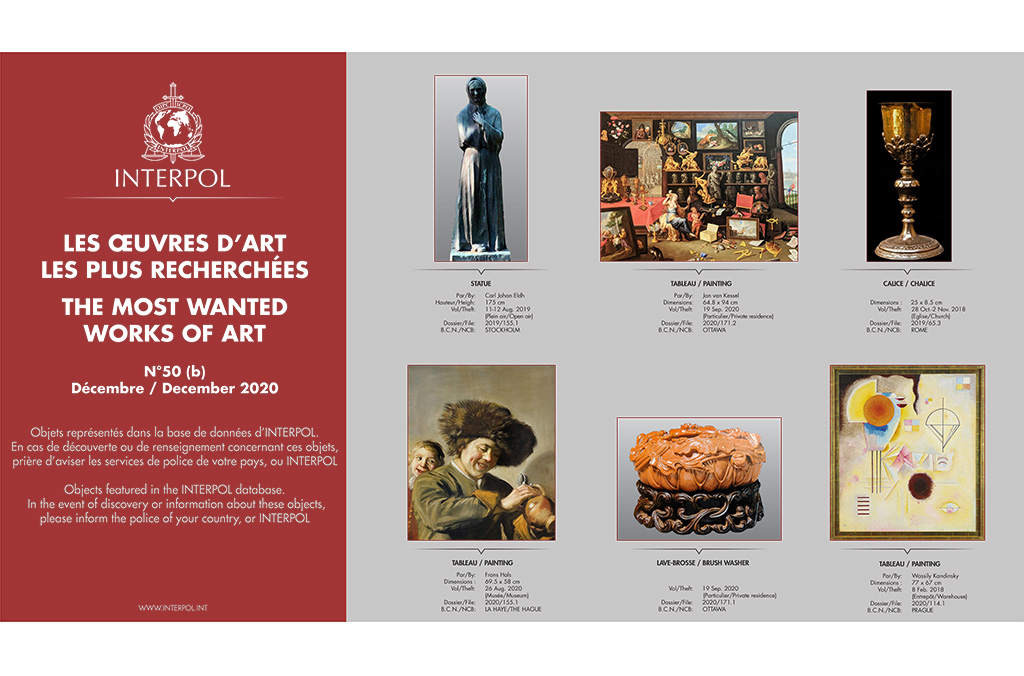

Every June and December, we highlight the most wanted works of art through a poster that is distributed to countries.

Police in Italy recently broke up a major international antiquities trafficking ring, seizing more than 3,500 ancient artifacts and arresting 21 people across multiple locations, in late May. The 21 detained suspects – 30 more remain at large – face charges that include criminal conspiracy, theft, and the illegal export of goods, according to a special unit dedicated to combatting the illicit trafficking of cultural property. The investigation by the Comando Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale, also known as the Carabinieri “Art Squad,” began last fall and uncovered several sites in southern Italy associated with the trafficking ring, including illegal dig sites and operational bases. During raids on the locations, police found ancient ceramics, jewelry, miniatures, and hundreds of bronze, gold, and silver coins dating from the 4th century B.C. to the 3rd century A.D. According to the police, the items have “inestimable historical, artistic, and commercial value.” Authorities also recovered excavation tools as well as documentation of illicit transactions in Italy and abroad. The criminal operation involved illicit actors at almost every stage of the process, including grave diggers, “fencers” (individuals who knowingly buy the stolen art to resell for a profit), and exporters (who facilitate sales of illegally sourced relics to auction houses and buyers abroad). Italy has taken a leading role on the issue of cultural heritage trafficking in the United Nations and more broadly.

The operation, which has been heralded by the Carabinieri and Italy’s Minister of Culture as a resounding success, starkly displays not only the vulnerability of ancient Italian artifacts to traffickers, but also the financial incentives that drive illicit actors to exploit cultural heritage more broadly. The estimated worth of the transnational trade in cultural heritage trafficking ranges from several hundred million to billions of dollars annually, according to the U.S. Congressional Research Service. Confidentiality, challenges in documenting provenance, the use of intermediaries, and inconsistent due diligence practices all contribute to the illegal trade. Moreover, archaeological sites and artifacts in countries with armed conflict, such as Iraq and Syria, are particularly vulnerable to trafficking and exploitation, as the chaos of war can enable illicit actors, including terrorists, to illegally obtain, circumvent due diligence practices, and, ultimately, profit from the sale of antiquities abroad. Islamic State’s exploitation of cultural heritage has helped finance the group’s activities and strengthened its ties with transnational organized crime. In response to this threat, the UN Security Council unanimously voted to adopt Resolution 2347 in 2017, warning that any trade involving ISIS, Al Nusra Front, or Al-Qaeda affiliates could constitute financial support for sanctioned entities.

Beyond the financial incentive, illicit actors have targeted and exploited cultural heritage to further their agendas – either by validating their narratives or providing financial gain – and to marginalize and stigmatize communities. The 2001 destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban, the 2014 destruction of the Sukur cultural landscape in Nigeria by Boko Haram, Islamic State’s destruction of historical and cultural sites and works of art in Palmyra, Syria, and the destruction of mausoleums in Timbuktu, Mali, by Ansar Dine and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Mahgreb all exemplify how terrorist groups target cultural heritage to strengthen their narratives. In doing so, these groups may seek to destroy a community’s collective cultural identity by targeting sites that the attackers might deem idolatrous to validate their own narrative, or they may target sites that are an integral part of the cultural or religious life of the community to subjugate their victims. Under the Rome Statute, these actions constitute war crimes. They have been prosecuted as such by the International Criminal Court. In 2016, a case was brought against a member of Ansar Dine for intentionally directing attack against religious and historic buildings in Timbuktu. In post-conflict contexts, the destruction of cultural heritage can hinder post-conflict recovery and peacebuilding efforts.

Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine highlights the role that state actors can play in the destruction of cultural heritage, and how the tactic can be used to obliterate a community’s collective identity. As of May 31, 2023, the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) had verified that over 250 sites in Ukraine had been damaged, with over 150 partially or totally destroyed, since the beginning of the invasion. These sites include religious sites, museums, monuments, libraries, and an archive. A 2022 New York Times investigation previously identified 339 cultural sites that sustained substantial damage, both as collateral damage and as a result of intentional targeting by Russian soldiers or pro-Russian separatists. Ukraine’s minister of culture, Oleksandr Tkachenko, told reporters last fall that almost 40 museums in Ukraine have been looted of artifacts by Russian soldiers. One of the looted items, a 1,500-year-old tiara dating back to the rule of Attila the Hun, is one of the world’s rarest and most valuable artifacts. By targeting cultural heritage in the conflict, Moscow appears to be intentionally working to eliminate Ukrainian cultural identity. According to the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, Alexandra Xanthaki, the invasion’s aim has been not merely the capture of territory, but “a gradual destruction of a whole cultural life.” She also said that “one of the justifications of the war is that Ukrainians don’t have a distinct cultural identity.” Particularly since the lead-up to the war and in the year since, Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly called Ukrainian nationhood and culture a fiction, claiming the country is rightful Russian territory that was improperly given statehood during the Soviet era. Russian state media has published propaganda calling for Ukraine’s total elimination. The role of state actors in the destruction of cultural heritage further complicates protection efforts, as states have often facilitated prevention, advocacy, documentation, and transitional justice efforts, and, as UN Security Council Resolution 2347 stresses, have the primary responsibility to protect their cultural heritage.