Sadly, yet once again, another tool for citizens seeking truth and or investigative journalists has been firewalled and stonewalled by government operatives.

Black columns run vertically down 700 pages, devoid of any information about the federal workers who spent thousands of hours doing union work while on the government payroll.

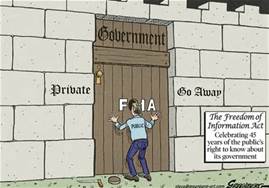

This is what the U.S. Department of Agriculture considers public disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act.

In the name of protecting employees’ privacy, USDA withheld their names, duty stations, job titles, pay grades and salaries. It even deleted names of the unions benefiting from the hours spent by these USDA workers who continued to draw full pay and benefits, courtesy of the taxpayers.

The level of secrecy is a stark example of the failings of FOIA, according to open government advocates. Agency bureaucrats are free to broadly interpret the nine exemptions in FOIA that allow them to withhold information about government employees and the documents they produce.

Interpretations vary about what information should be disclosed, despite directives from President Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder that there should always be a “presumption of openness” in weighing what to release.

The only recourse against an agency determined to keep its secrets is a costly lawsuit that can drag on for years.

“There are very strong incentives for agency officers to not release data, but there aren’t any incentives on the other side to release data,” said Ginger McCall, director of the open government program at the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a nonprofit group that advocates for transparency.

“There’s a real culture of secrecy within the agencies, and that is something that needs to be addressed,” McCall said.

A FOIA reform bill unanimously passed the House in February. It would put into law the presumption of transparency currently embodied in proclamations by the president and attorney general. But it would not change the FOIA exemptions that allow documents requested under FOIA to be withheld.

The USDA invoked the “personal privacy” exemption for federal employees to withhold data from the Washington Examiner.

Other FOIA exemptions cover things like national defense or foreign policy secrets, disciplinary actions, information about gas and oil wells and inter-agency memorandums.

FOIA reformers say the changes proposed in the House bill are positive, but without limiting the exemptions that can be invoked under FOIA, they are not likely to break the culture of secrecy at federal agencies.

“If we are really going to see the agencies apply the exemptions any differently we actually have to address some problems with the exemptions,” said Amy Bennett, assistant director of OpenTheGovernment, another nonprofit transparency group.

Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif., a sponsor of the bill, acknowledged the problem with FOIA lies in partly in the exemptions, which are left intact in the legislation.

Issa is chairman of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, and is co-sponsoring the FOIA bill with Rep. Elijah Cummings of Maryland, the ranking Democrat on the committee.

Putting the presumption favoring disclosure in the law will shift the burden to the agencies to show releasing requested information will cause specific harm, Issa said told the Examiner.

“FOIA exemptions are being abused,” Issa said. “Information should only be withheld if an agency reasonably believes it could cause specific, identifiable harm — not just because it is embarrassing or politically inconvenient.

“The bipartisan FOIA Oversight and Implementation Act will codify the ‘presumption of openness’ that the administration is fond of praising but does not practice,” Issa said.

“Along with other reforms that will improve agency compliance with FOIA, the ‘presumption of openness’ will combat the high number of inappropriate or unjustified redactions that prevent transparency,” he said.

In November 2012, the Examiner filed FOIA requests with 17 of the largest federal agencies seeking information about employees released from their regular jobs to do union work under “official time.”

The 3.4 million hours spent by union representatives cost taxpayers about $155.6 million in 2011, the latest year for which figures are available from the Office of Personnel Management.

The Examiner sought the name, title, duty station, pay grade, salary and hours spent for each agency employee released on official time, as well as the name of the union that benefited. None of that information is in the annual OPM report.

Several large agencies, including USDA, were unable to comply. The Examiner published a four-part series, “Too Big to Manage,” in February.

Most of the agencies that provided data did not invoke the privacy exemption, and released what information they had. A few, including the Department of Homeland Security, claimed the privacy exemption to withhold the names of employees, but provided the rest of the information.

The USDA finally responded to the FOIA request in mid-March 2014. FOIA Officer Alexis Graves claimed releasing employee and union data sought by the Examiner would “constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.”

Graves also said there is “minimal public interest, if any,” in the information.

The Examiner will appeal.

The USDA’s response is especially frustrating because of the lack of information available on the use of official time, said Rep. Dennis Ross, R-Fla., sponsor of a bill to mandate annual disclosure of basic information about the program.

Ross is pressuring OPM to update its latest report showing data from 2011.

“If these agencies, and the USDA in particular, have nothing to hide, then they should have no problem providing timely information on how their employees spend their time during work hours,” Ross said.

By releasing bits of irrelevant information, USDA officials will be able to claim in their annual FOIA tracking reports that they made a partial release to the Examiner, rather than an outright denial, McCall said.

“They do it to game the stats,” she said.

The wide range of responses to the Examiner request, from full disclosure to the USDA’s redactions, shows there is no consistency in how FOIA officers interpret the exemptions, said John Wonderlich, policy director at the Sunlight Foundation.

“That suggests the biggest variable in FOIA is agency willingness to comply,” Wonderlich said. “That’s not what it’s supposed to be.”

The proclamation of openness by Obama on his first full day in office is similar to declarations made by previous presidents, transparency advocates say.

But like other presidents, Obama has failed to break the secretive culture within federal bureaucracy and has adopted his own practices and policies that limit the release of information he sees fit to keep secret, they say.

An investigation by the Associated Press published March 16 found the Obama administration in 2013 censored government files or outright denied access to them under FOIA more often than ever .

The administration cited more legal exceptions it said justified withholding materials and refused a record number of times to turn over files quickly that might be especially newsworthy, the AP analysis found.

Click here to see more.