Maybe the FBI as well given Hillary? Spooky dude and his billons have twisted the system across the country. Perhaps he reached the White House as well, given the commuted sentences of criminals where Obama used his pen to release hundreds of felons. Is Soros paying senators on the Judiciary Committee for votes on Supreme Court Justice nominations?

It is no wonder violent felons never serve out their prison terms much less do the District Attorneys bother with the cases to begin with as noted by criminals on the streets with case files that are a mile long only to offend again.

George Soros’ quiet overhaul of the U.S. justice system

Politico: Progressives have zeroed in on electing prosecutors as an avenue for criminal justice reform, and the billionaire financier is providing the cash to make it happen.

While America’s political kingmakers inject their millions into high-profile presidential and congressional contests, Democratic mega-donor George Soros has directed his wealth into an under-the-radar 2016 campaign to advance one of the progressive movement’s core goals — reshaping the American justice system.

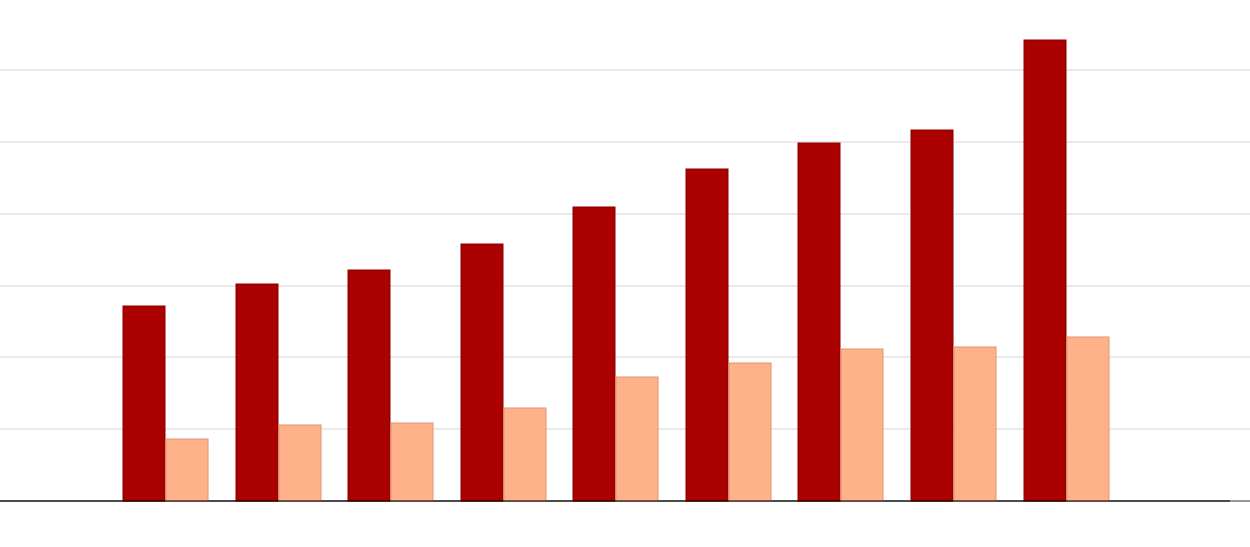

The billionaire financier has channeled more than $3 million into seven local district-attorney campaigns in six states over the past year — a sum that exceeds the total spent on the 2016 presidential campaign by all but a handful of rival super-donors.

His money has supported African-American and Hispanic candidates for these powerful local roles, all of whom ran on platforms sharing major goals of Soros’, like reducing racial disparities in sentencing and directing some drug offenders to diversion programs instead of to trial. It is by far the most tangible action in a progressive push to find, prepare and finance criminal justice reform-oriented candidates for jobs that have been held by longtime incumbents and serve as pipelines to the federal courts — and it has inspired fury among opponents angry about the outside influence in local elections.

“The prosecutor exercises the greatest discretion and power in the system. It is so important,” said Andrea Dew Steele, president of Emerge America, a candidate-training organization for Democratic women. “There’s been a confluence of events in the past couple years and all of the sudden, the progressive community is waking up to this.”

Soros has spent on district attorney campaigns in Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico and Texas through a network of state-level super PACs and a national “527” unlimited-money group, each named a variation on “Safety and Justice.” (Soros has also funded a federal super PAC with the same name.) Each organization received most of its money directly from Soros, according to public state and federal financial records, though some groups also got donations from nonprofits like the Civic Participation Action Fund, which gave to the Safety and Justice group in Illinois.

The Florida Safety and Justice group just poured nearly $1.4 million — all of which came from Soros and his 527 group — into a previously low-budget Democratic primary for state attorney in Central Florida before Tuesday’s vote. The group is backing Aramis Ayala, a former public defender and prosecutor, in her campaign against incumbent Jeff Ashton, whose jurisdiction covers over 1.6 million people across two counties in metro Orlando.

One TV ad from Florida Safety and Justice boosts Ayala, touting her “plan to remove bias so defendants charged with the same crime receive the same treatment, no matter their background or race.” The Soros-funded group is also attacking Ashton with ads saying he “got rid of protections that helped ensure equal treatment regardless of background or race. … Take two similar traffic incidents that happened on the same night. A white man got off with a slap on the wrist, while the black man faces prison.”

Opponents of Soros’ favored candidates have laced into the billionaire, saying that his influence has wildly tipped the scales of local elections and even charging that he made residents less safe.

“As a candidate and citizen of Caddo Parish, if an outsider was that interested in the race, I wanted to know exactly what he had in mind for the criminal justice system if he were to win,” said Dhu Thompson, a Louisiana attorney who lost a district attorney race to a Soros-backed candidate, James Stewart, in 2015. Soros gave over $930,000 — more than 22 times the local median household income — to the group boosting Stewart.

“I know some of his troubling opinions on social issues, especially the criminal justice system,” Thompson said. “I’ve never known him as an individual who was very strong on some of our crime and punishment issues. I felt it was very detrimental to the safety of Caddo Parish, and that’s why I took such a strong stand against him.”

A Soros representative declined to comment on his involvement in the DA races.

Progressive operatives and activists say that the recent uptick in news coverage of racial justice issues, especially police-involved deaths of African-Americans, helped sparked intense new interest in the powerful role of district attorneys, who did not indict officers in some high-profile cases. So has the longer-term reform push to shrink the U.S. prison population and promote treatment over punishment for drug users.

Reform groups have spent years advocating criminal justice policies and legislation that would reduce incarceration rates. Liberal donors have long given to policy-focused nonprofits; the Soros-chaired Open Societies Foundation, for example, works on drug policy and criminal justice reform and has supported other reform groups like the California-based Alliance for Safety and Justice — which, despite its similar name, has had no involvement in district attorney races, a spokeswoman said.

Prosecutorial discretion gives district attorneys a huge say in the charges and sentences that defendants face. But reform efforts have not traditionally focused on harnessing that power.

“They are often a very invisible part of the criminal justice system and the political system,” said Brenda Carter, director of the Reflective Democracy Campaign, an arm of the progressive Women Donors Network. “Many people can’t name their district attorney. It’s not an office people think about a lot.”

Carter’s group commissioned research in 2015 that found that 95 percent of elected local prosecutors in the U.S. are white and three-quarters overall are white men. It also highlighted a Wake Forest University study that found that a vast majority of prosecutors — 85 percent — run for reelection unopposed.

“I found that to be shocking, and I think people are waking up to the untapped potential for intervention in these seats to really change the day-to-day realities of criminal justice,” Carter said. “It’s been really gratifying for us to see the research taken up and run with by different groups around the country.”

Armed with that knowledge, progressive groups including Color of Change began researching potentially interesting district attorney races around the country, multiple sources said. (The organization declined to comment.)

“It’s hard to find this information!” exclaimed Steele, the Emerge America president. “You can’t just Google ‘hot DA races.’ So part of the issue is identifying what potential races there are.”

Soros’ spending started on these races about a year ago, when he put over $1 million into “Safety and Justice” groups that helped elect two new district attorneys in Louisiana and Mississippi and reelect a third — Hinds County, Miss., DA Robert Shuler Smith — who has since been charged by the Mississippi attorney general with improperly providing information to defendants.

The other Mississippi district attorney Soros’ spending helped elect, Scott Colom, has now represented a four-county stretch of the eastern part of the state for eight months. Colom said in an interview that he has focused on prosecuting violent crime in his new position while trying not to burden local prisons with first-time, low-level drug offenders.

“I’ve expanded the charges eligible for pre-trial diversion,” Colom said, adding that the number of people in the program in his jurisdiction has doubled since he took office seven months ago. “It’s all focused on the individual person, on trying to find a plan with the best chance possible of avoiding criminal behavior.”

“I’m sure there are plenty of people out there who think prison is too nice and we need to spend more on it,” Colom continued. “But it seems like a large majority of people out there get it and realize there have to be priorities. Just because a fella commits a crime doesn’t mean the best outcome is sending them to jail. … As much as possible, I want to take people from being tax burdens to taxpayers.”

After the Louisiana and Mississippi races, Soros next piled money into two of the biggest jurisdictions in the country: Houston’s Harris County (his lone losing effort so far) and Chicago’s Cook County, where he funded one of several groups that helped Kim Foxx defeat incumbent state’s attorney Anita Alvarez in a high-profile primary campaign dominated by the 13-month delay between the police shooting of Laquan McDonald and the indictment of the police officer involved.

In late spring, $107,000 from a Soros-funded New Mexico super PAC helped Raul Torrez win his Democratic district attorney primary by a 2-to-1 margin in Albuquerque’s Bernalillo County. Torrez’s Republican opponent dropped out of the general election soon after, citing the potentially exorbitant cost of opposing the Soros-backed candidate in the general election.

While Soros has spent heavily in 2015 and 2016, a broader national push into local prosecutor campaigns is expected to intensify in the next few years, thanks to longer-term planning and candidate recruitment. A Safety and Justice group has already organized in Ohio, according to campaign finance filings there. But it has not yet disclosed raising or spending any money.

“There’s been a realization that there’s not very much we can do this year, when you’re coming up to an election,” said Steele. “You have to have the right candidates. That’s a big piece of the puzzle and why I’m part of this conversation. … A lot of the conversations I’m having are about 2017 and 2018, about looking forward to next year in Virginia and other places.”

That means more local candidates should prepare for the shock of one of the biggest donors in American politics flooding their neighborhoods with ads.

Colom, the Mississippi prosecutor, says he has never met Soros — like other district attorney candidates supported by the Democratic billionaire this year. He said there was no hint that hundreds of thousands of dollars were coming to aid his campaign until advertising started pushing the same criminal-justice reform message that Colom had been touting — albeit on a much cheaper scale.

“The first I heard of it, someone told me they liked my radio ad, and I was thinking, that doesn’t sound like one of mine,” Colom said.

DailyMotion

DailyMotion

.png)