While the United States and coalition forces were providing military support in many forms to the Free Syrian Army and the Syrian Democratic Forces to destroy Islamic State, Russia has officially declared the exclusive victory.

Further, against the countless pro-Assad factions including Iranian militia and Russian forces, Bashir al Assad will remain in power and adhere to all edits from Moscow and Tehran.

The history city of Aleppo fell to Islamic State but such was not going to be the case again for Raqqa, the declared home for the terror group. Christians, Alawites and Druze all lived in Raqqa.

Yet how do Syrians and children find life and normalcy upon their return to Raqqa?

What remains is a modern day Hitleresque condition of destruction.

RAQQA, Syria—The municipal soccer stadium here was always called “The Black Stadium” because of its dark concrete construction, but that name took on a whole new meaning when it became an arena for horror under the rule of the so-called Islamic State.

Today, ISIS is gone and the bleachers are draped with the flags of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). This was the final redoubt of a handful of ISIS fighters, and when it fell last Friday, victory over that terror organization in its de facto capital was declared complete. But much of the city is destroyed, and for the few people who’ve made it back, memories of what life here was like are hard to retrieve.

“Before, we would play football matches here, before it came under Daesh [ISIS] control,” Issa Xabur, a 42-year-old civilian who once lived in Raqqa, told The Daily Beast as we explored precincts where the spectacle of death replaced the spectacle of sport. “The stadium became known for beheading people,” said Xabur. “It was used as a prison. Eighty percent of the people that were imprisoned here were killed.”

In the locker rooms, showers, and gym beneath the stadium, ISIS created cells and torture chambers for its feared security arm, known as the Amni.

One can still find graffiti written by prisoners and fighters. Some of it is in Russian, some in Arabic, some in English.

On one shattered wall, we read that “Hussam Alkjwan was killed in 25/2/2016.” We don’t know why. Beneath it in broken English, perhaps written by a jailer, is a list of reasons why someone could be arrested:

If you are reading this there’s four main reasons why you are Here!

1-You did the crime and caught Red Handed!

2-Using Tweeder [Twitter] GPS Locations! Or having GPS Locations switched upon turned ‘ON’ the Mobile Phone

3-Uploading videos and photos from a Sensitive Wifi internet source, i.e. You need your Amirs permission

4-A suspect! Off the street! The Police have good reason to do this!

It didn’t matter what you did or did not do, the ISIS police had “good reason” to bring you in.

And it didn’t matter that you might be waiting in this hole to die. You were supposed to keep the faith:

Be Patience, Be Patience, Be Patience!

The Enemy of the Muslims, Sataan will do every Whispering while [unclear]

Trust in Allah and lots of remembering of Allah, Dua [prayers] to Allah! …

Issa Xabur himself was arrested several times by ISIS and spent five days in this Black Stadium prison. “I couldn’t talk to anyone,” he told The Daily Beast. “They were hitting people with tires, and hanging people from the roof. People from Tunisia were responsible for torturing,” he said.

In the prison beneath the stadium we see iron cables and plastic straps used to tie people down. Other reporters have come across primitive exercise machines turned into bloodied instruments of torture. And in these dark corridors, mingled with the smell of dust and concrete, there is still the smell of human death.

“People were arrested when they were accused of being unbelievers, or of dealing with the coalition or the regime,” Xabur said.

Then, suddenly it’s evident that journalists are not the only ones interested in visiting the liberated stadium.

“Who are you working for?” demands a local SDF commander who seems to come out of nowhere. I am told to switch off my camera, and three soldiers in U.S. uniforms come into the prison to check it out. A few hours later, another group of U.S. soldiers arrives at the Black Stadium with cameras and a video drone.

Zagros, a Kurdish fighter with the SDF, sees a certain irony in all this U.S. military tourism. “The U.S. soldiers did not fight in the city of Raqqa,” he tells me. They provided support from behind the lines. “Now they come to see the prison.”

The situation for civilians in the last days of the Raqqa campaign was very difficult.

“We went as a group to a Daesh leader, who told us if you leave, we will kill you,” said Walid, 45, as we talked in a mosque. “There was no water or food, and we drank water that was not suitable for drinking,” he added.

“Whenever ISIS left a house, they booby-trapped it. My wife and mother died, but I am still alive. We were not allowed to leave during the liberation campaign.”

Ali, 21, is in the Ain al Issa refugee camp. He left Raqqa months ago after being imprisoned more than 10 times by ISIS, he says.

“I saw them killing the people with my own eyes. They tortured people, cut their hands, and heads,” he said.

By some accounts, in the final days of battle, after many Syrian members of ISIS were allowed out of the city under a truce, the few dozen foreign fighters in the Black Stadium held hundreds, or even thousands, of people as human shields. Ali thinks that the captured foreign fighters that held civilians hostage should be executed.

“They should be killed, because if they return [to their home countries], they will create problems as they did here,” he said.

ISIS flyers scattered around the city already are covered with dust, but they are easy enough to read. They show the many punishments ISIS carried out for spying, homosexuality, and theft.

Jihan Sheikh Ahmed, the official spokesperson for the SDF Raqqa campaign, left Raqqa before it came under ISIS control. “But my family lived for two years under Daesh rule,” she says. “It was a nightmare for them and for the people. [They] could not breathe freely or live freely. The children could not play in the street, and they terrorized the people by cutting their heads and thus imposing themselves in the name of the caliphate.”

The Black Stadium was not the only venue for atrocity. There was also Naim Square in the heart of the city.

“I was from Raqqa,” said a woman SDF commander during a celebration of the city’s liberation by women fighters in Naim Square. In the old days, she said, “we were coming to Naim Square to eat ice cream and take a walk. But after Daesh came here and announced its ‘state’ in this place, they spread killing among the people and instilled terror among them. Moreover, they brought children to watch the killings to terrorize their hearts.”

Nearby wrought iron fences were used like the pikes of old, to hold severed heads.

ISIS also enslaved many Yazidi women when they captured the town of Sinjar in August 2014. The region was the heartland of the non-Muslim minority. A few dozen of them were liberated in Raqqa when the SDF came in.

“They [ISIS] brought Yazidi women to Raqqa, to sell them here, kill our people, and cut off their hands and hang them here,” said the woman commander.

Even some ISIS wives who are now being held in a refugee camp in Ain al Issa feel sorry for the Yazidi women.

Aisha Khadad, a Syrian English teacher, was married to an imprisoned French ISIS member and said she rarely saw a slave out in the open in Raqqa. “They were sold to the emirs,” she said, and the emirs live mostly in Iraq.

“I was so sad for them,” Khadad told The Daily Beast. “Suddenly a man comes to your house who wants to rape you and use you as a slave.” And under the ISIS regime he had every right to do that.

SDF spokesperson Jihan Sheikh Ahmed now promises that they will change the mentality of the people of Raqqa who lived through these horrors.

“We want to return the children to their childhood, and when we beat Daesh, the hope of life is beginning to grow in the people again, and we want the people to understand that Daesh will never return, and when life returns to Raqqa, many things will change,” she said.

However, she added that it could take time for civilians to return. “They [ISIS] planted a lot of mines here, so we will form a military zone for two months to remove the mines, and then we start rebuilding the city,” she concluded.

When leaving the city, I could still see the human bones of victims of ISIS that were executed near the clock tower in Raqqa, and an ISIS flag still was flying over a destroyed building near the clock tower. And it made me think, “Even time will not erase all the wounds here.”

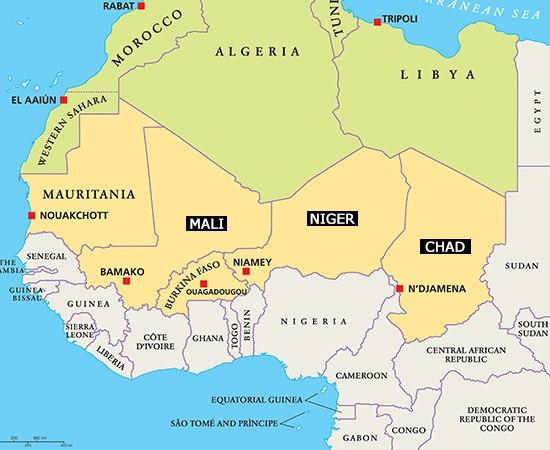

McCain and Graham both stated they were unaware of the operations in Niger, much less the other countries located in West Africa. The United States has an estimated 7000 troops operating in about 50 countries in Africa. Militant Islam has no boundaries globally.

McCain and Graham both stated they were unaware of the operations in Niger, much less the other countries located in West Africa. The United States has an estimated 7000 troops operating in about 50 countries in Africa. Militant Islam has no boundaries globally.

photo and more on each location courtesy of

photo and more on each location courtesy of