Remarks prepared for delivery.

Good morning. It’s great to be here with you, and great to be back here in my hometown. Thank you all for joining us. I want to thank Father McShane and Fordham for continuing to help us bring people together to focus on cyber security.

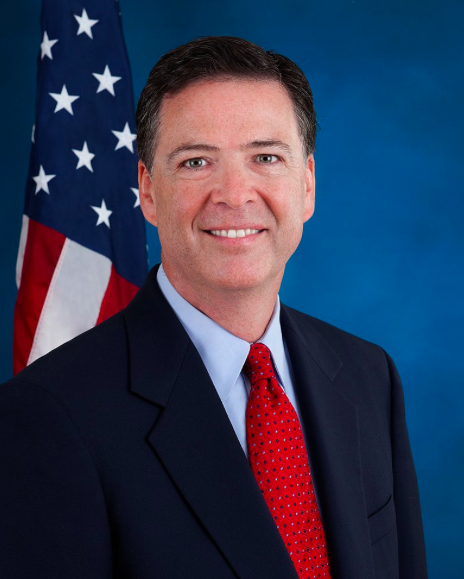

Let me start by saying how honored I feel to be here representing the men and women of the FBI. The almost 37,000 agents, analysts, and staff I get to work with at Headquarters, in our field offices, and around the world are an extraordinary, dedicated, and quite frankly, inspiring bunch. Not a day goes by that I’m not struck by countless examples of their patriotism, courage, professionalism, and integrity. And I could not be more proud, but also humbled, to stand with them as we face the formidable challenges of today—and tomorrow.

The work of the FBI is complex and hits upon nearly every threat facing our country. Today, I’d like to focus on the cyber threat.

Most of you have been thinking about the challenges in this particular arena for a long time. Before taking this job a few months ago, the last time I had to think seriously about cyber security through a law enforcement or national security lens was 12 years ago. Back then, I was head of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, which included the Computer Crimes and Intellectual Property Section and handled cyber investigations.

It’s safe to say that no area has evolved more dramatically since then, particularly given the blistering pace of technological change. And I’ve spent much of the past few months getting caught up on all things cyber. So maybe the most useful thing I can do today is to offer the viewpoint of someone who’s looking at this world with fresh eyes. I’d like to talk to you about what the cyber threat picture looks like today; what the FBI is doing about it; and most important of all, what’s the way forward? Where’s the threat going? And where do we need to be to meet that threat? And then if we have time, I hope to answer a few questions.

* * *

The cyber threat has evolved dramatically since I left DOJ in 2005. Back then, social media didn’t really exist as we know it today, and “tweeting” was something only birds did. Now…well, let’s just say it’s something that’s a little more on my radar. Today, we live much of our lives online, and everything that’s important to us lives on the Internet—and that’s a scary thought for a lot of people. What was once a minor threat—people hacking for fun or for bragging rights—has turned into full-blown economic espionage and lucrative cyber crime.

This threat now comes at us from all sides. We’re worried about a range of threat actors, from multi-national cyber syndicates and insider threats to hacktivists. We’re seeing an increase in nation-state sponsored computer intrusions. And we’re also seeing a “blended threat”—nation-states using criminal hackers to carry out their dirty work. We’re also concerned about a wide gamut of methods, from botnets to ransomware.

So what’s the FBI doing about the cyber threat? Realistically, we know we can’t prevent every attack, or punish every hacker. But we can build on our capabilities. We can strengthen our partnerships and our defenses. We can get better at exchanging information to identify the telltale signs that may help us link cyber criminals to their crimes. We can impose a variety of costs on criminals who think they can hide in the shadows of cyber space.

We can do all these things—and we are doing all these things.

We’re improving the way we do business, blending traditional investigative techniques with technical capabilities. We’re now assigning work based on cyber experience and ability, rather than on jurisdiction. We now have Cyber Action Teams of agents and experts who can deploy at a moment’s notice, much like our Counterterrorism Fly Teams. We also now have Cyber Task Forces in every field office—much like our Joint Terrorism Task Forces—that respond to breaches, conduct victim-based investigations, and collect malware signatures and other actionable intelligence.

So we’ve strengthened our investigative capabilities, but we need to do our best to actually lay hands on the culprits and lock them up. And even where we can’t reach them, we’re now using all the tools at our disposal—we’re “naming and shaming” them with indictments, and we’re seeking sanctions from the Treasury Department.

We’re also building on our partnerships. We’re working more closely with our federal partners, because this threat is moving so quickly that there’s no time for turf battles. It doesn’t matter if you call us, or DHS, or any other agency—we all work together, so your information will get where it needs to go and you’ll get the help you need. We care less about who you call than that you call, and that you call as promptly as possible.

We’re also working more closely with our foreign partners. We now have cyber agents embedded with our international counterparts in strategic locations worldwide, helping to build relationships and coordinate investigations.

We’re also trying to work better with our private sector partners. We’re sharing indicators of compromise, tactics cyber criminals are using, and strategic threat information whenever we can. I’m sure you can appreciate there are times when we can’t share as much as we’d like to, but we’re trying to get better and smarter about that.

The good news is, we’ve made progress on a number of important fronts. Just this past summer, we took down AlphaBay—the largest marketplace on the DarkNet. Hundreds of thousands of criminals were anonymously buying and selling drugs, weapons, malware, stolen identities, and all sorts of other illegal goods and services through AlphaBay. We worked with the DEA, the IRS, and Europol, and with partners around the globe, to dismantle the illicit business completely. But we were strategic about the takedown—we didn’t want to rush it and lose these criminals. So, we waited patiently and we watched. When we struck, AlphaBay’s users flocked to another DarkNet marketplace, Hansa Market, in droves—right into the hands of our Dutch law enforcement partners who were there waiting for them, and they shut down that site, too.

So we’re adapting our strategy to be more nimble and effective. But the bad news is, the criminals do that too.

I mentioned the “blended threat” earlier. Recently we had the Yahoo matter, where hackers stole information from more than 500 million Yahoo users. In response, last February we indicted two Russian Federal Security Service officers and two well-known criminal hackers who were working for them. That’s the “blended threat”—you have intelligence operatives from nation-states like Russia now using mercenaries to carry out their crimes.

In March, our partners in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrested one of the hackers in Canada. The other three are Russian citizens living in Russia, but we made the judgment that it was worth calling them out, so now they’re also fugitives wanted by the FBI—so their vacation destinations are more limited.

So we’re making strides and we’ve had a number of successes—but the FBI still needs to do more to adapt to meet the cyber challenge.

For example, we want to do more to mitigate emerging threats as they spread. While we may not be able to stop all threats before they begin, we can do more at the beginning to stop threats before they get worse. We can share information, identify signatures, and stop similar attacks from happening elsewhere. But to do that, we need the private sector to work with us. At the FBI, we treat victim companies as victims. So, please: When an intrusion affects critical infrastructure; when there’s a potential for impact to national security, economic security, or public health and safety; when an attack results in a significant loss of data, systems, or control of systems; or when there are indications of unauthorized access to—or malware present on—critical IT systems, call us. Because we want to help you, and our focus will be on doing everything we can to help you.

Another thing driving the FBI’s work is that at some point, we’ll have to stop referring to all technical and digital challenges as “cyber.” Sophisticated intrusions and cyber policy issues are very much at the forefront of the conversation. But we also have to recognize that there’s a technology and digital component to almost every case we have now.

Transnational crime groups, sexual predators, fraudsters, and terrorists are transforming the way they do business as technology evolves. Significant pieces of these crimes—and our investigations of them—have a digital component or occur almost entirely online. And new technical trends are making the investigative environment a lot more complex. The Internet of Things, for example, has led to phenomena like the Mirai botnet—malware that uses all these connected devices to overwhelm websites, like the attacks that took down Netflix and Twitter last year.

The digital environment also presents new challenges that the FBI has to address—all kinds of twists for us in terms of what’s coming down the pike. Advances like artificial intelligence or crypto currencies have implications not only for the commercial sector, but for national security. Encrypted communications are changing the way criminals and terrorists plan their crimes—I’ll have more to say on that in a moment. And the avalanche of data created by our use of technology presents a huge challenge for every organization.

I’m convinced that the FBI—like a lot of other organizations—hasn’t fully gotten our arms around these new technologies and their implications for our national security and cyber security work. On our end, we know we need to be working with the private sector to get a clearer understanding of what’s coming around the bend. We need to put our heads together, in conferences like this and in other ways, so we’re better prepared, not just to face current threats, but the threats that will come at us five, 10, and 15 years from now.

When I was last in government, I saw how the 9/11 attacks spurred the FBI to fundamentally transform itself into a more intelligence-based national security organization. In the same way, I believe the new digital environment demands further fundamental transformation from us.

Over the years, FBI investigators have made huge strides in responding to the investigative challenges posed by the digital realm. We have pockets of excellence and talent that we’ve relied on to tackle our most complex technical challenges. But with the wholesale rise of digital challenges, this model won’t work for us anymore. As a big organization spread across 56 field offices and over 80 international offices, we need a new approach. We’ve got to increase our digital literacy across the board.

Some of our smartest people are looking at these challenges and thinking strategically about how the entire FBI can evolve in this rapidly changing environment. We’re focused on building our digital capabilities. We’re also focusing on our people, making sure we continue to attract the right skills and talent—and develop the right talent internally.

One issue I’m fixated on is whether we’re recruiting, hiring, and training now the kind of tech-savvy people we’ll need in five or 10 years. We know that we need more cyber and digital literacy in every program throughout the Bureau—organized crime, crimes against children, white-collar crime, just to name a few. Raising the average digital proficiency across the organization will allow all of our investigators to counter threats more efficiently and effectively, while freeing our true cyber “black belts” to focus on the most vexing attacks, like nation-state cyber intrusions.

We also need to focus more on innovation, approaching problems in new ways, with new ideas—which isn’t something, to be honest, that always comes naturally in government. We can’t just rely on the way we’ve always done things. And I don’t mean just technological innovation; I mean innovation in how we approach challenges, innovation in partnerships, innovation in who we hire, innovation in how we train, and innovation in how we build our workforce for the future.

So we need more innovation, and more of the right people. But the FBI can’t navigate the digital landscape alone. We also need to build stronger partnerships—with our counterparts in federal agencies, with our international counterparts, with the cyber research community, and with the private sector. And we need to do a better job of focusing our combined resources—trying to get our two together with your two to have it somehow equal more than four; to make it five or six or seven.

Finally, in some cases we may need lawmakers to update our laws to keep pace with technology. In some ways, it’s as if we still had traffic laws that were written for the days of the horse-and-carriage. The digital environment means we don’t simply need improved technical tools; we also need legal clarifications to address gaps.

* * *

I want to wrap up by talking about two challenges connected to the digital revolution. The first is what we call the “Going Dark” problem. This challenge grows larger and more complex every day. Needless to say, we face an enormous and increasing number of cases that rely on electronic evidence. We also face a situation where we’re increasingly unable to access that evidence, despite lawful authority to do so.

Let me give you some numbers to put some meat on the bones of this problem. In fiscal year 2017, we were unable to access the content of 7,775 devices—using appropriate and available technical tools—even though we had the legal authority to do so. Each one of those nearly 7,800 devices is tied to a specific subject, a specific defendant, a specific victim, a specific threat.

I spoke to a group of chief information security officers recently, and someone asked about that number. They basically said, “What’s the big deal? There are millions of devices out there.” But we’re not interested in the millions of devices used by everyday citizens. We’re only interested in those devices that have been used to plan or execute criminal or terrorist activities.

Some have argued that having access to the content of communications isn’t necessary—that we have a great deal of other information available outside of our smart phones and our devices; information including transactional information for calls and text messages, or metadata. While there’s a certain amount we can glean from that, for purposes of prosecuting terrorists and criminals, words can be evidence, while mere association between subjects isn’t evidence.

Being unable to access nearly 7,800 devices is a major public safety issue. That’s more than half of all the devices we attempted to access in that timeframe—and that’s just at the FBI. That’s not even counting a lot of devices sought by other law enforcement agencies—our state, local, and foreign counterparts. It also doesn’t count important situations outside of accessing a specific device, like when terrorists, spies, and criminals use encrypted messaging apps to communicate.

This problem impacts our investigations across the board—human trafficking, counterterrorism, counterintelligence, gangs, organized crime, child exploitation, and cyber. And this issue comes up in almost every conversation I have with leading law enforcement organizations, and with my foreign counterparts from most countries—and typically in the first 30 minutes.

Let me be clear: The FBI supports information security measures, including strong encryption. But information security programs need to be thoughtfully designed so they don’t undermine the lawful tools we need to keep this country safe.

While the FBI and law enforcement happen to be on the front lines of this problem, this is an urgent public safety issue for all of us. Because as horrifying as 7,800 in one year sounds, it’s going to be a lot worse in just a couple of years if we don’t find a responsible solution.

The solution, I’ll admit, isn’t so clear-cut. It will require a thoughtful and sensible approach, and may vary across business models and technologies, but—and I can’t stress this enough—we need to work fast.

We have a whole bunch of folks at FBI Headquarters devoted to explaining this challenge and working with stakeholders to find a way forward. But we need and want the private sector’s help. We need them to respond to lawfully issued court orders, in a way that is consistent with both the rule of law and strong cybersecurity. We need to have both, and can have both.

I recognize this entails varying degrees of innovation by the industry to ensure lawful access is available. But I just don’t buy the claim that it’s impossible.

For one thing, many of us in this room use cloud-based services. You’re able to safely and securely access your e-mail, your files, and your music on your home computer, on your smartphone, or at an Internet café in Tokyo. In fact, if you buy a smartphone today, and a tablet in a year, you’re still able to securely sync them and access your data on either device. That didn’t happen by accident. It’s only possible because tech companies took seriously the real need for both flexible customer access to data and cyber security. We at the Bureau are simply asking that law enforcement’s lawful need to access data be taken just as seriously.

Let me share just one example of how we might strike this balance. Some of you might know about the chat and messaging platform called Symphony, used by a group of major banks. It was marketed as offering “guaranteed data deletion,” among other things. That didn’t sit too well with the regulator for four of these banks, the New York State Department of Financial Services. DFS was concerned that this feature could be used to hamper regulatory investigations on Wall Street.

In response to those concerns, the four banks reached an agreement with the Department to help ensure responsible use of Symphony. They agreed to keep a copy of all e-communications sent to or from them through Symphony for seven years. The banks also agreed to store duplicate copies of the decryption keys for their messages with independent custodians who aren’t controlled by the banks. So the data in Symphony was still secure and encrypted—but also accessible to regulators, so they could do their jobs.

I’m confident that with a similar commitment to working together, we can find solutions to the Going Dark problem. After all, America leads the world in innovation. We have the brightest minds doing and creating fantastic things. If we can develop driverless cars that safely give the blind and disabled the independence to transport themselves; if we can establish entire computer-generated virtual worlds to safely take entertainment and education to the next level, surely we should be able to design devices that both provide data security and permit lawful access with a court order.

We’re not looking for a “back door”—which I understand to mean some type of secret, insecure means of access. What we’re asking for is the ability to access the device once we’ve obtained a warrant from an independent judge, who has said we have probable cause.

We need to work together—the government and the technology sector—to find a way forward, quickly.

In other parts of the world, American industry is encountering requirements for access to data—without any due process—from governments that operate a little differently than ours, to put it diplomatically. It strikes me as odd that American technology providers would grant broad access to user data to foreign governments that may lack all sorts of fundamental process and rule of law protections—while at the same time denying access to specific user data in countries like ours, where law enforcement obtains warrants and court orders signed by independent judges.

I just cannot believe that any of us in this room thinks that paradox is the right way to go. That’s no way to run a railroad, as the old saying goes.

A responsible solution will incorporate the best of two great American traditions—the rule of law and innovation. But for this to work, the private sector needs to recognize that it’s part of the solution. We need them to come to the table with an idea of trying to find a solution, as opposed to trying to find a way to build systems to prevent a solution. I’m open to all kinds of ideas, because I reject this notion that there could be such a place that no matter what kind of lawful authority you have, it’s utterly beyond reach to protect innocent citizens. I also can’t accept that anyone out there reasonably thinks the state of play as it exists now—and the direction it’s going—is acceptable.

Finally, let me briefly mention another issue that has a huge effect on the FBI’s national security work, including cyber—the re-authorization of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA.

The speed and scope of the cyber threat demands that we use every lawful, constitutional tool we’ve got to fight it. Section 702 is one of those tools.

I want to stress once again how vital this program is for the FBI’s national security mission. Section 702 is an essential foreign intelligence authority that permits the targeted surveillance of non-U.S. persons overseas. It’s especially valuable to the FBI, because it gives us the agility we need to stay ahead of today’s rapidly changing global threats.

I bring all this up today because unless renewed by Congress, Section 702 is set to expire later this month. Without 702, we would open ourselves up to intelligence gaps that would make it easier for bad cyber actors and terrorists to attack us and our allies—and make it harder for us to detect these threats.

We simply can’t afford for that to happen. So the FBI has spent an enormous amount of time, as have our partners in the intelligence community, working together with Congress to find a way to re-authorize Section 702 while addressing their concerns. My fervent hope is that before the extension expires, Congress will re-authorize Section 702 in a manner that doesn’t significantly affect our operational use of the program, or endanger the security of the American people.

* * *

So that’s a perspective on cyber from the new guy back on the block.

If one thing’s become clear to me after immersing myself again in this world for the past few months, it’s the urgency of the task we all face. High-impact intrusions are becoming more common; the threats are growing more complex; and the stakes are higher than ever.

That requires all of us to raise our game—whether we’re in law enforcement, in government, in the private sector or the tech industry, in the security field, or in academia. We need to work together to stay ahead of the threat and to adapt to changing technologies and their consequences—both expected and unexpected. Because at the end of the day, we all want the same thing: To protect our innovation, our systems, and, above all, our people.

Thank you all for everything you’re doing to make the digital world safer and more secure, and for joining us here in New York. I look forward to working with you in the years to come.

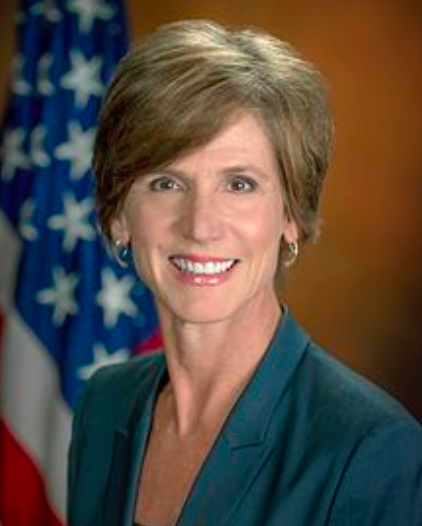

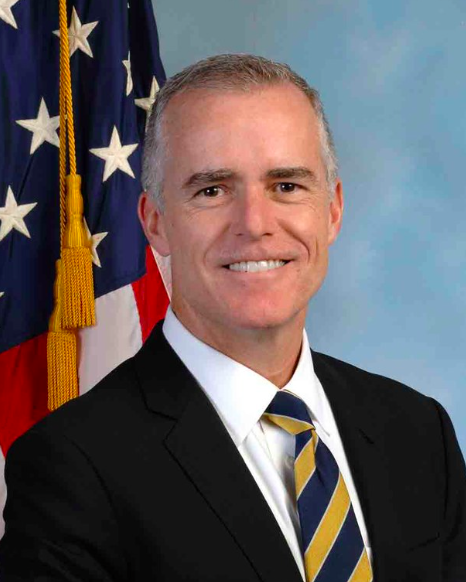

****  photo

photo

The FBI’s mission in cybersecurity is to counter the threat by investigating

intrusions to determine criminal, terrorist, and nation-state actor identities, and engaging in activities

to reduce or neutralize these threats. At the same time, the FBI collects and disseminates information significant to those responsible for defending networks, including information regarding threat actor targets and techniques.

The FBI’s jurisdiction is not defined by network boundaries; rather, it includes all territory governed by

U.S. law, whether domestic or overseas, and spans individual citizens, private industry, critical

infrastructure, U.S. government, and other interests alike. Collectively, the FBI and its federal partners

take a whole-of-government approach to help deter future threats and bring closure to current threats

that would otherwise continue to infiltrate and harm our network defenses.

In July 2015, the FBI, in coordination with foreign law enforcement partners, dismantled a computer

hacking forum known as Darkode, which was a one-stop, high-volume shopping venue for some of the

world’s most prolific cyber criminals. This underground, password-protected online forum was a

meeting place for those interested in buying, selling, and trading malware, botnets, stolen personally

identifiable information, and other pieces of data and software that facilitated complex global cyber

crimes. As the result of this multi-year investigation, called Operation Shrouded Horizon, the FBI’s

Cyber Division and international partner agencies took down Darkode through coordinated law

enforcement action.

This international takedown involved Europol and 20 cooperating countries and is

believed to be the largest coordinated law enforcement operation to date against a forum based criminal

enterprise. Operation Shrouded Horizon resulted in charges, arrests, and searches of 70 Darkode

members and associates including indictments in the United States against 12 individuals associated

with the forum including the administrator. As part of the law enforcement action, the FBI seized

Darkode’s domain name and servers. This operation highlighted the FBI Cyber Division’s mission to

identify, pursue, and defeat cyber adversaries targeting global U.S. interests through collaborative