Five Clinton friends who got special State Department access

WashingtonExaminer: Hillary Clinton’s campaign has struggled to explain a batch of previously undisclosed emails that contain fresh evidence of cooperation between the State Department and donors to the Clinton Foundation.

The records, which emerged through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by conservative-leaning Judicial Watch, offered a narrow window into the extent to which friends and donors were afforded consideration and access above what was provided to other outsiders.

The emails revived questions about whether the former secretary of state maintained an appropriate distance from her family’s philanthropy. While State Department officials denied suggestions that the documents produced any evidence of impropriety, Clinton’s critics took her to task Wednesday for allegedly selling influence through the foundation.

As the Democratic nominee labors to repair a public trust that was damaged badly by the FBI’s investigation into her private email use, the signs of quid pro quo contained in the latest records will likely force Clinton to confront the long-simmering controversy surrounding her family’s foundation.

Gilbert Chagoury

Several of the most controversial emails came from the inbox of Douglas Band, a longtime Clinton aide who was then serving in a top role at the Clinton Foundation. Band went on to found a consulting firm, Teneo Strategies, whose work with clients that had interests before the State Department raised red flags.

Band wrote Huma Abedin, Clinton’s deputy chief of staff, in April 2009 to demand a major Clinton Foundation donor be given access to the State Department’s “substance person” on Lebanon.

Gilbert Chagoury, the Lebanese-born Nigerian businessman who had written checks to the Clinton Foundation, has a long history of giving to Clinton causes — even when election laws did not permit him to do so. His $460,000 donation to a group accused of funneling foreign contributions to the Democratic National Committee in 1997 earned him an invitation to dine at the White House with the Clintons amid a congressional probe into the arrangement.

Chagoury’s ties to the Clinton State Department have come under fire in the past due to the former secretary of state’s refusal to place Boko Haram, a Nigerian terror group, on the official list of foreign terrorist organizations. Sen. David Vitter, R-La., wrote to the State Department last year to inquire about the delay in designating Boko Haram a terrorist outfit and whether it was related to Chagoury’s proximity to Clinton.

Band stressed in his email to Abedin that the Chagoury request was “very important” and instructed her to reach out to the donor immediately.

Jennifer Granholm, a former governor of Michigan and current Clinton surrogate, attempted to dismiss Wednesday any association between the Clinton Foundation and the State Department’s rush to grant Chagoury access to a high-ranking official.

“Well, I mean, I wasn’t in the State Department at the time,” Granholm said during an appearance on CNN. “But I do know that [Clinton] has abided by the ethics agreement she signed at the beginning, which was not to take any action on the part of the State Department that mixed foundation business.”

Granholm said Band had reached out to Abedin in his capacity as a representative of former President Bill Clinton, not as an employee of the family’s charity.

Even that explanation, if true, would not eliminate all the potential conflicts of interest at play, as Bill Clinton netted generous speaking fees from Nigerian entities linked to Chagoury.

Wall Street executive

Hillary Clinton welcomed a Feb. 2009 meeting with Stephen Roach, a top executive at Morgan Stanley, after Roach slipped her a copy of the testimony he planned to deliver before Congress the following week.

The Democratic nominee instructed her staff to arrange a time to meet Roach, who then ran the bank’s Asian operations, in Beijing during her upcoming swing through southeast Asia.

Morgan Stanley has given up to $500,000 to the Clinton Foundation, donor records show. Roach had personally donated heavily to Clinton’s past political campaigns, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

The testimony Roach delivered encouraged U.S. officials to dial back the tough talk on China and embrace trade deals that included Beijing’s interests. The Morgan Stanley executive chastised politicians for saddling Wall Street with the blame for economic failures and encouraged the U.S. to address a receding middle class “without derailing globalization.”

In an interview with a Chinese television station and separate remarks alongside the Chinese foreign minister just days later, Clinton echoed many of Roach’s points about the need for Americans to save more of their paychecks and for China to increase its consumption of American goods.

It is unclear whether Roach’s inside access to Clinton persuaded her to hew closely to the views on Chinese trade he had laid out for her.

But the timing of his communications with Clinton raises questions about whether Roach exerted influence over the former secretary of state.

What’s more, the Beijing tryst was not the only time Clinton took advice from the Morgan Stanley executive.

In July 2010, Clinton told Roach she was “delighted” to receive an email from him and solicited his thoughts on upcoming bilateral talks about the economy with the Chinese. She again pushed her staff to schedule a meeting with Roach.

Morgan Stanley executives have given extensively to Clinton’s presidential campaign, despite her promise to crack down on the excesses of Wall Street.

Lobbyist access

When Jonathan Mantz, the former finance director for Hillary Clinton’s 2008 campaign who had become a lobbyist, reached out to the secretary of state in Feb. 2009 to share some “great news,” Hillary Clinton instructed her assistant to add him to a list of people she was scheduled to call.

The email exchange offered a brief glimpse into what appeared to be a profitable friendship for both Mantz and Hillary Clinton.

For example, Mantz agreed to assist in steering his client’s funds toward one of Hillary Clinton’s pet projects: the U.S. pavilion at the Shanghai Expo. The State Department could not spend taxpayer money on the project, which many experts viewed as a diplomatic priority, so Hillary Clinton dispatched her aides to drum up funding from the same network of donors that funds the Clinton Foundation.

In June 2009, Kris Balderston, the aide charged with soliciting much of the funding for the pavilion, told Hillary Clinton that Mantz was “engaged” in the project, along with Pepsi, Microsoft and General Electric (all foundation donors).

In March 2010, Balderston informed his boss that Delos Living, a real estate company he described as “a Mantz client,” had kicked in $250,000 for the pavilion.

Within a year, Delos Living, whose board included Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, was tapped for a $5 million effort to build a soccer stadium in Haiti with the Clinton Global Initiative.

Mantz personally earned $280,000 for the “strategic counsel” services he provided Delos Living, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

Unidentified job seeker

In April 2009, Band approached Abedin and Cheryl Mills, then Hillary Clinton’s chief of staff, about hiring at the State Department an individual whose name was redacted.

Band forwarded an email in which the individual had expressed gratitude for an “eye-opening” trip to Haiti, where the Clinton Foundation claims to have done extensive work. The foundation official told Mills and Abedin that it was “important to take care of” the unnamed individual.

“Personnel has been sending him options,” Abedin replied.

Elizabeth Trudeau, a State Department spokeswoman, refused to reveal the identity of the individual Wednesday but argued her agency brings in many different people for many different reasons.

“The department regularly hires political appointees with a range of skill sets,” Trudeau said.

The spokeswoman declined to say whether the person was put in a government position by Hillary Clinton’s team. If he was, it would not have been the first time a donor received a plush appointment.

In 2011, Hillary Clinton’s aides rushed a top secret security clearance for Rajiv Fernando, a wealthy Chicago businessman, so he could serve on the International Security Advisory Board.

When reporters asked for a copy of his resume, State Department officials panicked and stripped Fernando of his position for fear that his lack of credentials would come under scrutiny.

Consulting connections

Hillary Clinton asked Abedin in April 2009 whether she should reach out to a Pentagon official on behalf of Jackie Newmyer, a longtime friend and president of a consulting firm called Long Term Strategy Group.

Emails made public by the State Department suggest Newmyer secured meetings with Department of Defense officials by the following month about landing a contract for her firm.

In March, Newmyer had prepared for Hillary Clinton a proposal in the hopes of winning a consulting deal with the State Department.

Newmyer aimed to advise the administration on Iran, among other things, as the U.S. moved toward its controversial negotiations with the country.

*****

Not complete without George Soros has access and influence, right? Poor Ambassador Stevens never had the access or influence with Hillary Clinton, nor did any of those survivors or the dead from Benghazi.

Leaked e-mail shows Soros urged Clinton to intervene in Albania civil unrest

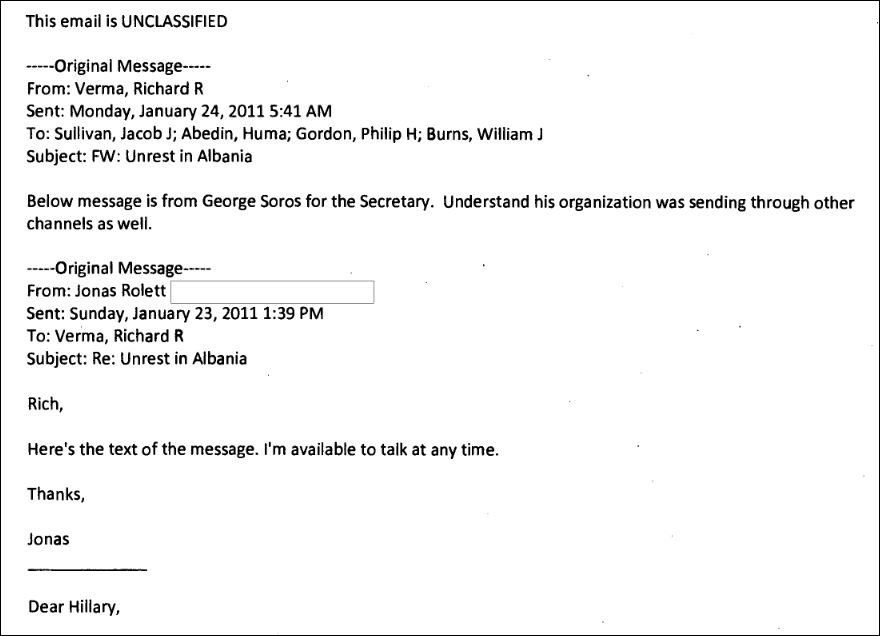

More leaked e-mails from Hillary Clinton’s time as Secretary of State prove that she was taking foreign policy advice from left-wing billionaire activist George Soros.

An e-mail provided by WikiLeaks showed Soros reaching out to Secretary Clinton over a foreign policy dispute in Albania.

“Dear Hillary,

“A serious situation has arisen in Albania which needs urgent attention at senior levels of the US government. You may know that an opposition demonstration in Tirana on Friday resulted in the deaths of three people and the destruction of property.

“There are serious concerns about further unrest connected to a counter-demonstration to be organized by the governing party on Wednesday and a follow-up event by the opposition two days later to memorialize the victims.

“The prospect of tens of thousands of people entering the streets in an already inflamed political environment bodes ill for the return of public order and the country’s fragile democratic process.”

Soros urges the then-Secretary of State to get the international community involved and pressure the Prime Minister to “forestall further demonstrations” and “tone down public pronouncements” as well appointing a senior European official to act as the mediator.

The left wing billionaire also gave Clinton a list of potential nominees to appoint as mediator: Carl Bildt, Martti Ahtisaari and Miroslav Lajcak.

The e-mail was sent from Soros’ aide to Richard Verma, then the Assistant Secretary of State for Legislative Affairs who forwarded it to several of Clinton’s top aides including Huma Abedin, Jacob Sullivan, and Philip Gordon. Sullivan forwarded it to Clinton.

Just three days after Clinton received the e-mail from Soros the EU ended up sending Soros’ suggested nominee Lajcak to mediate the civil unrest, the BBC reported.

June 8, 2016: Opponents of a proposed sugary drink tax demonstrate outside City Hall in Philadelphia.

June 8, 2016: Opponents of a proposed sugary drink tax demonstrate outside City Hall in Philadelphia.