A faithful reader of this website, reached out to me and asked for an update on a previous post. Hat tip for this great reminder. Grrr….when looking at the dollars, it has hard not to jump and down in frustration.

With a little effort in research, the last time the Government Accountability Office did any estimate to the cost of the U.S. economy for all things illegal/immigration related was 2011.

The cost at the State level fluctuates based on deportations and beds available. The Federal government out of the Justice Department helps pay respective states for the costs of alien incarceration. It must be understood that aliens come from hundreds of countries and since there are some countries that allegedly refuse to take back their citizens by deportation, at least the Justice Department should work all the diplomatic channels that the home countries of the criminals should pay up for all expenses and associated future costs.

Three groups of criminal aliens can be distinguished.

All criminal aliens include both unauthorized aliens, most of whom are potentially removable, and legal aliens10 who may or may not be removable depending on specific crimes committed. This population contains the set of criminal aliens who are removable on the basis of specific crimes committed.

Criminal aliens who have been convicted of removable criminal offenses are subject to removal under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) even if they are otherwise legally present.11 For example, a legal permanent resident (LPR) convicted of cocaine possession is subject to removal,12 but an LPR convicted of public intoxication is not. This population also includes aggravated felons.

Criminal aliens who have been convicted of aggravated felonies13 are ineligible for most forms of relief from removal14 and are ineligible to be readmitted to the United States.15

As noted above, all three of these subpopulations—criminal aliens, removable criminal aliens, and aggravated felons—comprise an unknown mix of legally present noncitizens and unauthorized aliens.

State by state and listed by country, click here for what the Bureau of Justice released for FY 2016.

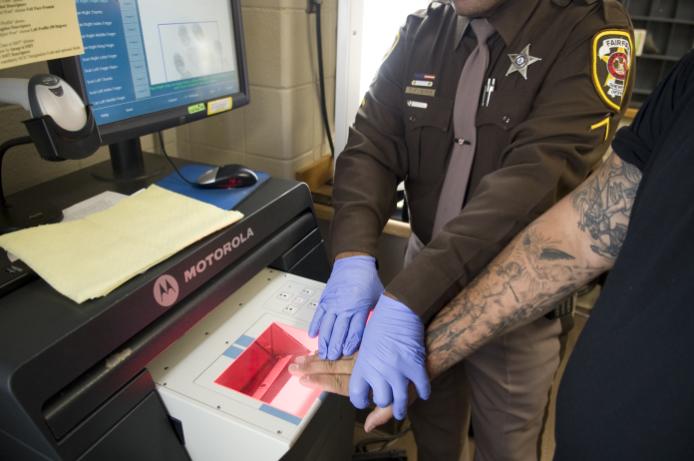

The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice, administers SCAAP, in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). SCAAP provides federal payments to states and localities that incurred correctional officer salary costs for incarcerating undocumented criminal aliens who have at least one felony or two misdemeanor convictions for violations of state or local law, and who are incarcerated for at least 4 consecutive days during the reporting period.

SCAAP Legislative Authority

SCAAP is governed by Section 241(i) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. § 1231(i), as amended, and Title II, Subtitle C, Section 20301, Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, Pub. L. 103-322. In general terms, if a chief executive officer of a state or a political subdivision exercises authority over the incarceration of undocumented criminal aliens and submits a written request to the U.S. Attorney General, the Attorney General may provide compensation to that jurisdiction for those incarceration costs. SCAAP is subject to additional terms and conditions of yearly congressional appropriations.

***

Related reading: OFFICE OF JUSTICE PROGRAMS

ADDITIONAL GUIDANCE REGARDING COMPLIANCE WITH 8 U.S.C. § 1373

****

Just a view from the State of Texas for aliens that are not being detained or incarcerated as noted in a report from 2013:

In part from FAIRUS.org: In 2013, illegal immigration cost Texas taxpayers about $12.1 billion annually. That amounts to more than $1,197 for every Texas household headed by a native-born or naturalized U.S. citizen. The taxes paid by illegal aliens — estimated at $1.27 billion per year — do not come close to paying for those outlays, but we include an estimate of revenue from sales taxes, property taxes, alcohol taxes, and cigarette taxes.

Examining Texas’s fiscal outlays from the perspective of the current debate over adopting an amnesty for illegal aliens, we find that the fiscal burden to taxpayers would not be significantly lessened even if an amnesty like that proposed in the Senate’s S.744 were enacted. In fact, it becomes clear that the only way to significantly reduce the fiscal burden is to reduce the size of the population that illegally entered the country. State and local policymakers have options available to accomplish that objective. In Arizona, efforts to discourage the arrival of additional illegal residents and to hold employers accountable for knowingly hiring illegal workers have been effective in reducing the illegal alien population and, thereby, the fiscal costs associated with that population.

A draft executive order circulating on social media Wednesday indicates the U.S. military could be used to establish and secure refugee camps in Syria. (Via Twitter)

A draft executive order circulating on social media Wednesday indicates the U.S. military could be used to establish and secure refugee camps in Syria. (Via Twitter)