Wiretaps are nothing new and for law enforcement it is a top investigative tool to solving cases. All wiretaps must have a well define probable cause in order for the application to be approved. This particular case however is a head-scratcher where real answers are still not forthcoming.

***

With a single wiretap order, US authorities listened in on 3.3 million phone calls

The order was carried out in 2016 as part of a federal narcotics investigation.

NEW YORK, NY — US authorities intercepted and recorded millions of phone calls last year under a single wiretap order, authorized as part of a narcotics investigation.

The wiretap order authorized an unknown government agency to carry out real-time intercepts of 3.29 million cell phone conversations over a two-month period at some point during 2016, after the order was applied for in late 2015.

The order was signed to help authorities track 26 individuals suspected of involvement with illegal drug and narcotic-related activities in Pennsylvania.

The wiretap cost the authorities $335,000 to conduct and led to a dozen arrests.

But the authorities noted that the surveillance effort led to no incriminating intercepts, and none of the handful of those arrested have been brought to trial or convicted.

The revelation was buried in the US Courts’ annual wiretap report, published earlier this week but largely overlooked.

“The federal wiretap with the most intercepts occurred during a narcotics investigation in the Middle District of Pennsylvania and resulted in the interception of 3,292,385 cell phone conversations or messages over 60 days,” said the report.

Details of the case remain largely unknown, likely in part because the wiretap order and several motions that have been filed in relation to the case are thought to be under seal.

It’s understood to be one of the largest number of calls intercepted by a single wiretap in years, though it’s not known the exact number of Americans whose communications were caught up by the order.

We contacted the US Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, where the wiretap application was filed, but did not hear back.

Albert Gidari, a former privacy lawyer who now serves as director of privacy at Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society, criticized the investigation.

“They spent a fortune tracking 26 people and recording three million conversations and apparently got nothing,” said Gidari. “I’d love to see the probable cause affidavit for that one and wonder what the court thought on its 10 day reviews when zip came in.”

“I’m not surprised by the results because on average, a very very low percentage of conversations are incriminating, and a very very low percent results in conviction,” he added.

When reached, a spokesperson for the Justice Department did not comment.

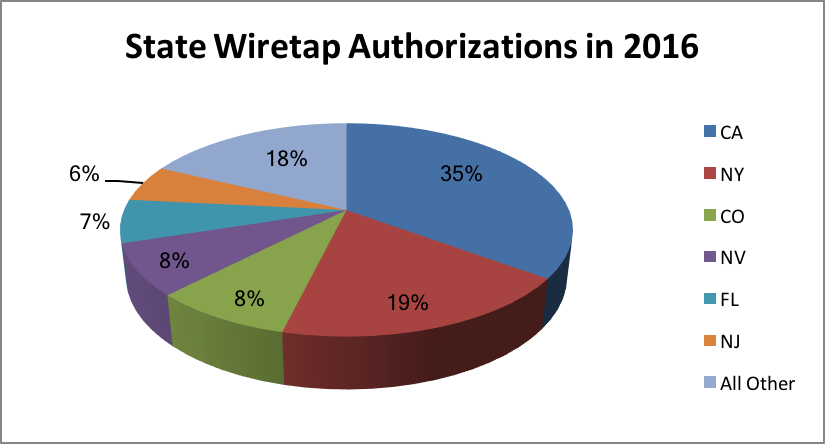

Seventy-seven federal jurisdictions submitted reports of wiretap applications for 2016. For the third year in a row, the District of Arizona authorized the most federal wiretaps, approximately 9 percent of the applications approved by federal judges.

Federal judges and state judges reported the authorization of 600 wiretaps and 177 wiretaps, respectively, for which the AO received no corresponding data from prosecuting officials. Wiretap Tables A-1 and B-1 (which will become available online after July 1, 2017, at http://www.uscourts.gov/statistics-reports/analysis-reports/wiretap-reports) contain information from judge and prosecutor reports submitted for 2016. The entry “NP” (no prosecutor’s report) appears in these tables whenever a prosecutor’s report was not submitted. Some prosecutors may have delayed filing reports to avoid jeopardizing ongoing investigations. Some of the prosecutors’ reports require additional information to comply with reporting requirements or were received too late to include in this document. Information about these wiretaps should appear in future reports.

Peter Smith/NYDailyNews

Peter Smith/NYDailyNews