In the days ahead, it appears that Russia and the rogue friends they keep will respond to the West likely by a obscure cyber war. Take personal caution with your financial activity.

The other warning is news reports for are specific assassination attempts covered to look as suicide. While we heard about the poison assassination attempt in Salisbury, England of Skripal and his daughter, the United States had it’s own successful assassination in 2015 of Mikhail Lesin in Washington DC. Additionally, the UK had two another successful wet jobs as it is called going back to 20o6 and 2010. Those victims were Alexander Litvinenko and Gareth Williams who worked for GCHQ

There are many other hit operations that happened in Russia including the recent death of Maxim Borodin.

There are an estimated 250+ journalists that have been killed since the fall of the Soviet Union.

So, it is now declared that the United Nations quit counting the dead from the Syria civil war since the number has officially exceeded 500,000. What is disgusting however is, we sorta care about the dead but the methods no longer matter unless chemical weapons are used. How nuts is that? So, France, Britain and the United States respond to the most recent attack –>  photo

photo

check – round one of airstrikes

check – round two of airstrikes

Let’s give credit where credit is due. By John Hannah

First, U.S. President Donald Trump set a red line and enforced it. He warned that the large-scale use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime would trigger a U.S. attack. When Syrian President Bashar al-Assad crossed that red line a year ago, Trump responded with 59 cruise missiles that took out about 20 percent of Syria’s operational aircraft. A year later, Trump has acted again after Assad chose to challenge him a second time. This attack was twice as big and hit multiple targets, including what U.S. defense officials called the “heart” of Syria’s chemical weapons program, substantially degrading Assad’s ability to produce the deadly agents.

That ain’t peanuts. No, there’s no guarantee it will end Assad’s use of chemical weapons — in which case Trump and his military have made clear that they’ll strike again, almost certainly harder than the time before. And no, nothing that happened Friday night will, in isolation, alter the trajectory of Syria’s bloody civil war. But the effective deployment of U.S. power in defense of a universal norm barring the use of some of the world’s worst weapons against innocent men, women, and children is nevertheless to be applauded — limited an objective as it may be. Also to be praised is the possible emergence of a commander in chief whose threats to use force need to be taken seriously by U.S. adversaries. Once established, this kind of credibility (while no panacea) can be a powerful instrument in the U.S. foreign-policy arsenal. Once lost, it is hard to recover, and the consequences can be severe. For evidence, just see the post-2013 results, from Crimea to Syria.

A second important virtue of Friday night’s attack was its multilateral character. With barely a week’s notice, Britain, France, and the United States, the three most powerful militaries of the trans-Atlantic alliance, all permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, seamlessly operated on the seas and in the skies of the Middle East to defend their common interests and values against a murderous Russian and Iranian client. What’s the worth of that kind of unity, coordination, and seriousness of purpose? It’s hard to quantify precisely. But anyone who’s ever toiled as a practitioner in the national security space knows, deep in their bones, that it matters — a lot. And it especially matters in the case of a U.S. president who has too often unfairly — and, to my mind, dangerously — discounted the value of Europe, the West, and the post-World War II system of institutions and alliances that his predecessors built. In that power and righteousness of the world’s leading liberal democracies acting in concert, there’s a significant value-added that no mere counting of ships, planes, and missiles can adequately capture. Kudos to the president and his team for their skill in mounting this posse. It’s an important framework that they hopefully will continue to invest in to confront the multitude of urgent international challenges now staring us in the face.

A few other related observations: Say what you will about the wisdom of some of the president’s public messaging last week, but once he made clear that he again would act to enforce his red line, U.S. adversaries took him deadly seriously. Russian ships dispersed from port. Syria abandoned its own air bases and rushed to co-locate its aircraft near Russian military assets. And Iranian-backed fighters, including Hezbollah forces, allegedly vacated certain positions and went to ground for fear of a possible U.S. strike. Again, the fact that the United States’ worst adversaries appear to take Trump’s threats with the seriousness they deserve is a very good thing, a genuine national security asset that needs to be husbanded, reinforced, and carefully but systematically exploited going forward. But hopefully last week’s experience also serves as a reminder to the president of the deep wisdom inherent in the criticism that he’s long leveled at his predecessors: Don’t telegraph your military punch.

Another observation: There was much nervous hand-wringing before the strike about a possible U.S.-Russia confrontation. Rightly so. No one wants World War III to break out over Syria. All prudent and appropriate measures should be taken to mitigate those risks. But in some circles, the hyping of the concern threatened to become absolutely paralyzing, a justification (or excuse) for doing nothing in the face of Assad’s abominable use of weapons of mass destruction.

In the end, of course, for all their chest thumping, the Russians did next to nothing as Western planes and missiles flew under their noses to strike a client that they’ve expended significant resources to save.

Just as the Israelis, for their part, have conducted nearly 100 strikes against Russia’s Iranian, Hezbollah, and Syrian allies with barely more than a clenched fist from Moscow. The fact is that for all the firepower they may have assembled in Syria, and for all the success they’ve enjoyed carpet-bombing defenseless civilian populations and poorly equipped Islamist radicals, Russian forces are severely overmatched — both in terms of quality and quantity — by what the United States and its allies can bring to bear in any head-to-head confrontation in the eastern Mediterranean. Putin knows it. So does his military. That reality of the actual balance of power — not only militarily, but economically and diplomatically as well — is always worth keeping in mind.

On their own, the Syrians and their Iranian allies were virtually defenseless against the U.S.-led strike. The best they had was a flurry of unguided missiles haphazardly fired after the mission’s designated targets had been turned to smoldering ruins. Of course, it was only a few years ago (well before the Russians intervened with their advanced S-400 surface-to-air batteries) that senior U.S. officials were pointing to the dangers of Assad’s air defenses as an excuse for not acting to protect Syrian civilians from being systematically terrorized by barrel bombs, indiscriminate artillery fire, and Scud missiles. Let’s hope that the overwhelming success of this attack puts the reality of that threat into somewhat better perspective for U.S. military planners — while also serving as a powerful reminder not just to Assad, but to Iran and other adversaries as well, of the extreme vulnerability they potentially face at the hands of U.S. air power and weaponry.

My criticisms of the U.S. strike? It was clearly at the lowest end of the options presented the president. As suggested by some of what I’ve said above, Trump was too risk-averse. Even with the president telegraphing that a strike was coming, the universe of targets that the United States could have attacked — while still minimizing collateral damage and the threat of great-power escalation — was far larger than what it ended up hitting. Trump could have done much more to degrade the Assad regime’s overall capability to wage war against its own people. The United States could have sent far more powerful messages to the Syrian government’s key military and intelligence power nodes of the risks they run to their own survival through mindless obedience to Assad’s genocidal criminality. Ditto the Russians and Iranians, and the realization that their failure to reign in the most psychotic tendencies of their client could substantially raise the costs and burdens of their Syrian venture if they’re not careful.

In short, everything the United States wanted to do with the strike — hold Assad accountable, re-establish deterrence against the use of chemical weapons, send a message to the Russians and Iranians about the price to be paid for failing to control their client, and move toward a credible political settlement — could have been done more effectively, at acceptable risk, with a significantly larger strike.

More fundamentally, I have deep concerns about what appears to be the president’s emerging strategy in Syria. It amounts to defeating the Islamic State, deterring the use of chemical weapons, and then withdrawing U.S. forces as quickly as possible from eastern Syria. As for the more strategically significant menace posed to vital U.S. interests by an aspiring Iranian hegemon seeking to dominate the Middle East’s northern tier, drive the United States out of the region, and destroy Israel, the administration’s strategy is not particularly compelling. As best as one can tell from the president’s recent statements — including the one he made on Friday night announcing the Syria strike — it amounts to encouraging some combination of regional allies (and perhaps Russia) to fill the vacuum the United States leaves behind.

That kind of abdication of U.S. leadership rarely works out well. Leveraging U.S. power to demand greater burden-sharing from partners who have even more at stake than the United States does? Definitely. Less effective: When the United States washes its hands of a problem with deep implications for U.S. national security in vague hope that other parties — smaller, weaker, more deeply conflicted and strategically myopic than the United States is — will organically rise to the occasion and mobilize a virtuous coalition that takes care of business and keeps at bay the country’s most vicious adversaries.

The president is right, of course: The Middle East is a deeply troubled place. There are no great victories to be won there. There is no glory to be gained. Just worst disasters to be avoided, threats contained, and important national interests preserved. Yes it is imperative that the United States does so smartly, prudently, by, with and, through local partners and multilateral coalitions, using all instruments of national power, and in a way that sustains the understanding and support of the American people. But do so the country must. Packing its bags and vacating the playing field to the likes of Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah is escapism masquerading as strategy. Trump’s important response to the Syrian chemical weapons attack last week is evidence that he may still be capable of grasping that unforgiving reality. He should be encouraged to build on it.

John Hannah

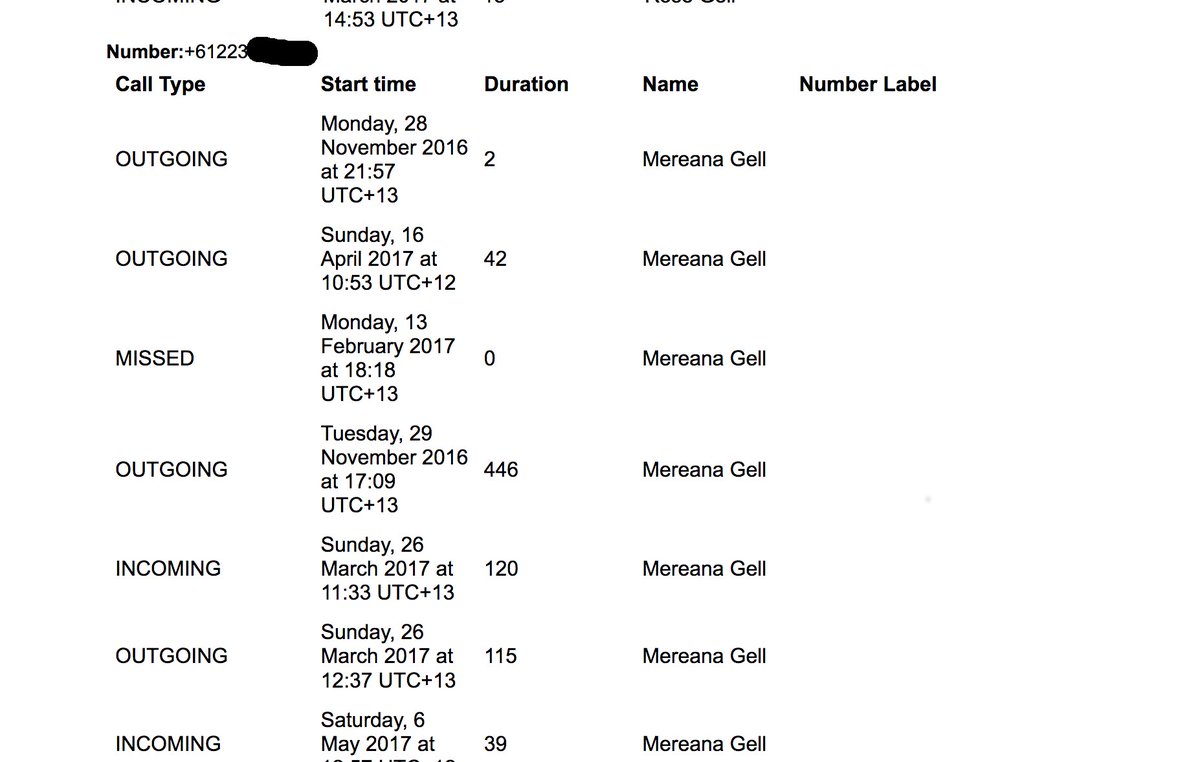

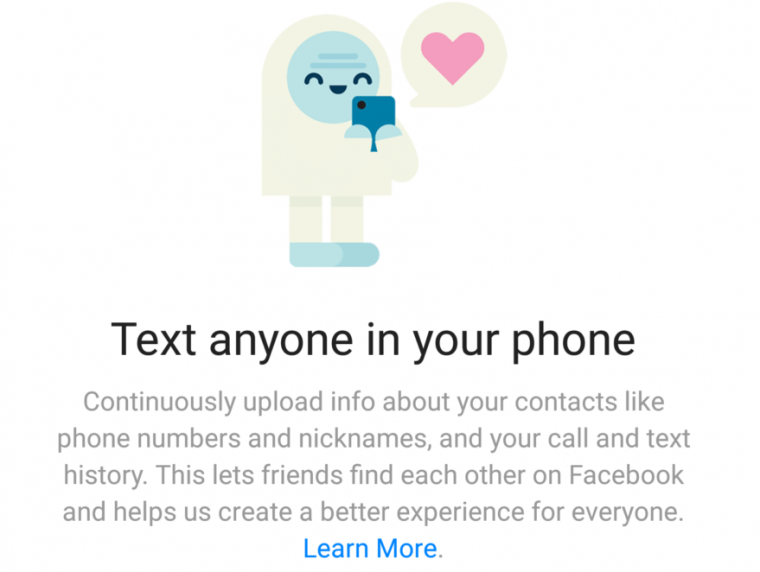

This screen in the Messenger application offers to conveniently track all your calls and messages. But Facebook was already doing this surreptitiously on some Android devices until October 2017, exploiting the way an older Android API handled permissions.

This screen in the Messenger application offers to conveniently track all your calls and messages. But Facebook was already doing this surreptitiously on some Android devices until October 2017, exploiting the way an older Android API handled permissions.