So, the most immediate Executive Order signed by President Biden was to shutter the Keystone XL pipeline project. It has devastated the energy industry and the true costs to Americans are still growing outside the scope of higher prices of gasoline and the loss of jobs. The effects include revenues to states that provide funding the public education, tax increases, alterations in foreign policy and relations, slowing economic recovery across many industry sectors and destabilizing power sources for businesses and homes. For some finer points and financial context, go here.

But, did you know the United States is actually funding a pipeline across Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India? Yes, in all the peace talks with the Taliban, we have for decades been providing financial aid, the amount is too convoluted to determine but this goes back to collaboration between the United States and the Taliban and even Russia.

A Taliban delegation has paid a surprise visit to Turkmenistan to pledge support for a planned natural gas pipeline across Afghanistan, providing welcome reassurance for a project whose viability has long been rendered doubtful by security concerns.

Signs point to the trip having been brokered by the U.S. government, which has long championed what is known as TAPI, named after the four countries the pipeline would cross: Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Other projects alluded to by the Taliban spokesman are the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan high-voltage power transmission lines, or TAP, and railways from Turkmenistan to Afghanistan.

Should such reassurances hold, the main hurdle facing TAPI’s developers would be raising the necessary funds. Estimated costs for the project have been placed at anywhere up to $10 billion, although the chief executive of the TAPI Pipeline company, Muhammetmyrat Amanov, stated in 2018 that he was forecasting outlays closer to $7 billion.

Global energy majors have latterly shown no enthusiasm for TAPI, but that was not always the way. In 1997, a consortium comprised of six companies and the government of Turkmenistan was formed with the goal of building a 1,271-kilometer pipeline to Pakistan. India was not yet part of the plan. The largest share in that consortium, 54 percent, was held by California-based Unocal Corporation. In 1997, the American company even arranged travel to Texas for a senior Taliban delegation for negotiations. Deadly terrorist attacks in 1998 against U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya organized by Al-Qaeda, whose leader Osama bin Laden had been provided safe haven by the Taliban, put paid to all that.

The Taliban was not entirely deterred, though. In 1999, the militant group, which had by then extended its control to almost all of Afghanistan, entered into talks on the route with Turkmenistan and Pakistan. Lack of cash and the rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape made it all pointless. By the end of that year, Turkmenistan had reached an agreement with Russia’s Gazprom on the delivery of 20 billion cubic meters of gas in 2000. source

source

Breakthroughs on the Afghan and Caspian fronts come at an extremely propitious time for Turkmenistan, which has struggled to find viable buyers for its vast gas reserves.

Turkmenistan is currently almost entirely reliant on China. Russia buys paltry amounts of gas.

Since the launch of the Central Asia-China pipeline in 2009, Turkmenistan has pumped 290 billion cubic meters of gas to China. But whereas it was once predicted that the Beijing-funded pipeline would be carrying 65 billion cubic meters of Turkmen gas annually by 2020, the entire route still only has capacity for 55 billion cubic meters per annum, and both Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan also use the pipeline.

Considering Turkmenistan has the fourth-largest reserves of natural gas in the world – an estimated 19.5 trillion cubic meters, nearly 10 percent of the world’s total – current export figures nowhere near reflect its potential. source

Crazy huh?

But hold on…there is the matter of Biden cancelling the border wall construction between the United States and Mexico.

Border walls around the world is a sign of the times and the Unites States also provides some foreign funding for walls far away. Someone ask Joe, Jen or Kamala about this…

Going back to 2016, Donald Trump promoted the construction of the border wall while the rest of the critics attacked the whole mission. The Atlantic in part included some of the top complaints. Clinton is suggesting that walls are useless against today’s borderless threats. Obama is suggesting that the world is marching toward ever-more interconnectedness, trampling the walls in its way. Both seem to present walls as a thing of the past. In fact, though, border walls and fences are currently going up around the world at the fastest rate since the Cold War

Ramo, a former journalist and the co-CEO and vice chairman of the consulting firm Kissinger Associates, applies network theory to international affairs. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War helped usher in unfettered globalization, he argues, but now a backlash is underway. Globalization has gradually produced a desire in certain parts of the world for separation—particularly after a series of traumas, including the 9/11 attacks and the global financial crisis, exposed the hazards of freewheeling integration. And separation is increasingly being achieved through physical barriers.

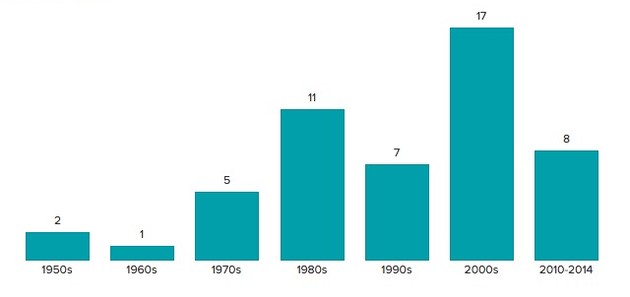

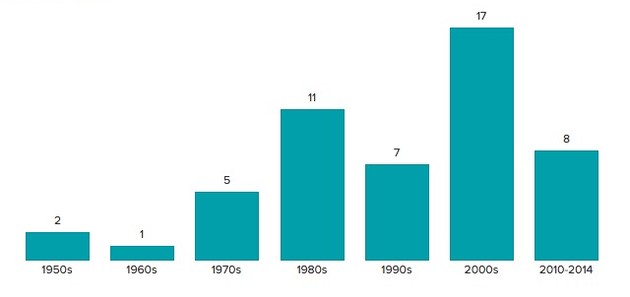

The statistic Ramo cites about the spread of walls comes from a study by the political scientists Ron Hassner and Jason Wittenberg: Of the 51 fortified boundaries built between countries since the end of World War II, around half were constructed between 2000 and 2014. Hassner and Wittenberg found that such boundaries—structures like the existing U.S.-Mexico border fence, the Israel-West Bank barrier, and the Saudi Arabia-Yemen border fence—tend to be constructed by wealthy countries seeking to keep out the citizens of poorer countries, and that many of these fortifications have been built between states in the Muslim world.

“The walls, fences, and trenches of the modern world seem to be getting longer, more ambitious, and better defended with each passing year,” Ramo writes. “The creation of gates is … the corollary of connection.”

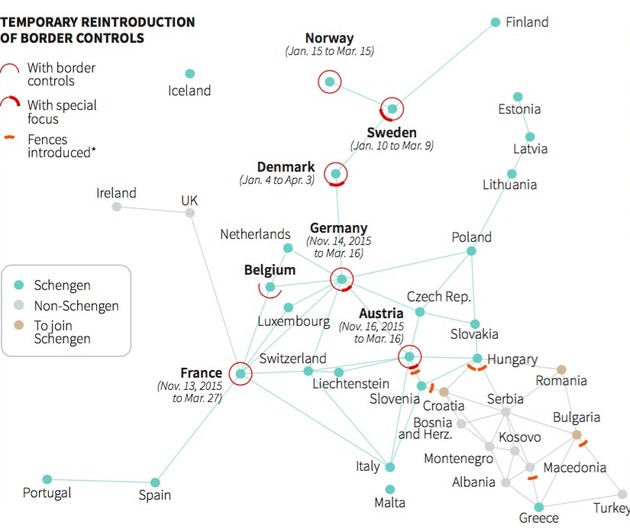

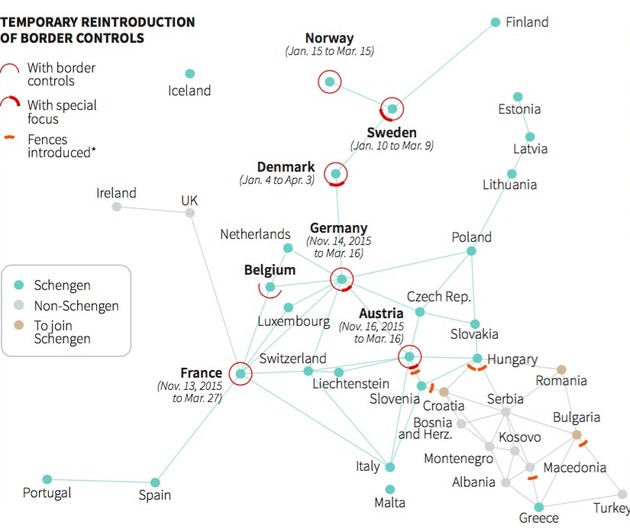

Recently, many of those fences have been appearing in Europe, as countries there struggle to process an influx of migrants and refugees. (The chart above doesn’t account for all of these new barriers, a number of which have been constructed since 2014.) The Economist observed in January that, as a result of the refugee crisis and the conflict in Ukraine, “Europe will soon have more physical barriers on its national borders than it did during the Cold War.” New border controls and barriers, including Austria’s proposed fence along the border with Italy, are threatening the viability of the European Union’s passport-free Schengen zone.

“Talking about walls or no walls is not the right discussion,” Ramo added. He would rather the discussion be about how gatekeeping should work, including questions like “what kind of immigration do we want to encourage and how do we want to structure that process.”

“Talking about walls or no walls is not the right discussion,” Ramo added. He would rather the discussion be about how gatekeeping should work, including questions like “what kind of immigration do we want to encourage and how do we want to structure that process.”

One of the reasons these trends are important is that they reframe the 2016 election from a contest between the past and the future, as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama imply, to one between two plausible futures. Ramo might call it a divide over the relative wisdom of more open versus more closed networks.

For an interactive migrant map for recent years go here.

Hypocrisy right? The Daily Mail of the UK did a piece in 2015 of 65 countries that have erected walls and fences.

“Talking about walls or no walls is not the right discussion,” Ramo added. He would rather the discussion be about how gatekeeping should work, including questions like “what kind of immigration do we want to encourage and how do we want to structure that process.”

“Talking about walls or no walls is not the right discussion,” Ramo added. He would rather the discussion be about how gatekeeping should work, including questions like “what kind of immigration do we want to encourage and how do we want to structure that process.”

France’s President Emmanuel Macron jokes with President Trump. Photo by Tatyana Zenkovich/AFP/Getty Images.

France’s President Emmanuel Macron jokes with President Trump. Photo by Tatyana Zenkovich/AFP/Getty Images.