Remember when the Democrats and lobby groups ridiculed George W. Bush for using a color coded threat matrix? Carry on….

The White House now has a color-coded scale for cyber-security threat

TheVerge: As the Obama administration nears its final months, the White House has released a framework for handling cyberattacks. The Presidential Policy Directive on United States Cyber Incident Coordination builds on the action plan that Obama laid out earlier this year, and it’s intended to create a clear standard of when and how government agencies will handle incidents. It also comes with a new threat level scale, assigning specific colors and response levels to the danger of a hack.

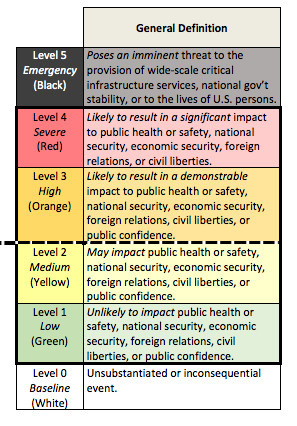

The cyberattack severity scale is somewhat vague, but it’s supposed to make sure that the agencies involved in cybersecurity — the Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, and Office of the Director of National Intelligence — respond to threats with the same level of urgency and investment. A Level One incident is “unlikely to impact public health or safety, national security, economic security, foreign relations, civil liberties, or public confidence,” while a red Level Four one is “likely to result in a significant impact to public health or safety, national security, economic security, foreign relations, or civil liberties.” One final designation — Level Five, or black — covers anything that “poses an imminent threat to the provision of wide-scale critical infrastructure services, national government stability, or to the lives of US persons.”

The upshot of this is that anything at Level Three or above will trigger a coordination effort to address the threat. In addition to the groups above, this effort will include the company, organization, or agency that was attacked.

Cybersecurity is a growing concern, and both Congress and the White House have spent the past several years pushing various frameworks for shoring it up. This includes a series of hotly debated bills that culminated in the Cyber Information Sharing Act, which has raised privacy questions as it’s been put into practice. At the same time, high-profile hacks have led to serious consequences for companies like Sony Pictures, Target, and Ashley Madison. Most recently, an unknown hacker or hackers — potentially linked to Russia — breached the Democratic National Committee’s servers, releasing large numbers of embarrassing documents and emails. This announcement doesn’t tell us exactly how the federal government will handle future cyberattacks, but along with everything else, it does signal that they’re becoming a more and more standard part of the security equation.

*****

From the White House FACT SHEET: Presidential Policy Directive

The PPD builds on these lessons and institutionalizes our cyber incident coordination efforts in numerous respects, including:

- Establishing clear principles that will govern the Federal government’s activities in cyber incident response;

- Differentiating between significant cyber incidents and steady-state incidents and applying the PPD’s guidance primarily to significant incidents;

- Categorizing the government’s activities into specific lines of effort and designating a lead agency for each line of effort in the event of a significant cyber incident;

- Creating mechanisms to coordinate the Federal government’s response to significant cyber incidents, including a Cyber Unified Coordination Group similar in concept to what is used for incidents with physical effects, and enhanced coordination procedures within individual agencies;

- Applying these policies and procedures to incidents where a Federal department or agency is the victim; and,

- Ensuring that our cyber response activities are consistent and integrated with broader national preparedness and incident response policies, such as those implemented through Presidential Policy Directive 8-National Preparedness, so that our response to a cyber incident can seamlessly integrate with actions taken to address physical consequences caused by malicious cyber activity.

We also are releasing today a cyber incident severity schema that establishes a common framework within the Federal government for evaluating and assessing the severity of cyber incidents and will help identify significant cyber incidents to which the PPD’s coordination procedures would apply.

Incident Response Principles

The PPD outlines five principles that will guide the Federal government during any cyber incident response:

- Shared Responsibility – Individuals, the private sector, and government agencies have a shared vital interest and complementary roles and responsibilities in protecting the Nation from malicious cyber activity and managing cyber incidents and their consequences.

- Risk-Based Response – The Federal government will determine its response actions and resource needs based on an assessment of the risks posed to an entity, national security interests, foreign relations, or economy of the United States or to the public confidence, civil liberties, or public health and safety of the American people.

- Respecting Affected Entities – Federal government responders will safeguard details of the incident, as well as privacy and civil liberties, and sensitive private sector information.

- Unity of Effort – Whichever Federal agency first becomes aware of a cyber incident will rapidly notify other relevant Federal agencies in order to facilitate a unified Federal response and ensure that the right combination of agencies responds to a particular incident.

- Enabling Restoration and Recovery – Federal response activities will be conducted in a manner to facilitate restoration and recovery of an entity that has experienced a cyber incident, balancing investigative and national security requirements with the need to return to normal operations as quickly as possible.

Significant Cyber Incidents

While the Federal government will adhere to the five principles in responding to any cyber incident, the PPD’s policies and procedures are aimed at a particular class of cyber incident: significant cyber incidents. A significant cyber incident is one that either singularly or as part of a group of related incidents is likely to result in demonstrable harm to the national security interests, foreign relations, or economy of the United States or to the public confidence, civil liberties, or public health and safety of the American people.

When a cyber incident occurs, determining its potential severity is critical to ensuring the incident receives the appropriate level of attention. No two incidents are the same and, particularly at the initial stages, important information, including the nature of the perpetrator, may be unknown.

Therefore, as part of the process of developing the incident response policy, the Administration also developed a common schema for describing the severity of cyber incidents, which can include credible reporting of a cyber threat, observed malicious cyber activity, or both. The schema establishes a common framework for evaluating and assessing cyber incidents to ensure that all Federal departments and agencies have a common view of the severity of a given incident, the consequent urgency of response efforts, and the need for escalation to senior levels.

The schema describes a cyber incident’s severity from a national perspective, defining six levels, zero through five, in ascending order of severity. Each level describes the incident’s potential to affect public health or safety, national security, economic security, foreign relations, civil liberties, or public confidence. An incident that ranks at a level 3 or above on this schema is considered “significant” and will trigger application of the PPD’s coordination mechanisms.

Lines of Effort and Lead Agencies

To establish accountability and enhance clarity, the PPD organizes Federal response activities into three lines of effort and establishes a Federal lead agency for each:

- Threat response activities include the law enforcement and national security investigation of a cyber incident, including collecting evidence, linking related incidents, gathering intelligence, identifying opportunities for threat pursuit and disruption, and providing attribution. The Department of Justice, acting through the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force (NCIJTF), will be the Federal lead agency for threat response activities.

- Asset response activities include providing technical assets and assistance to mitigate vulnerabilities and reducing the impact of the incident, identifying and assessing the risk posed to other entities and mitigating those risks, and providing guidance on how to leverage Federal resources and capabilities. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), acting through the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC), will be the Federal lead agency for asset response activities. The PPD directs DHS to coordinate closely with the relevant Sector-Specific Agency, which will depend on what kind of organization is affected by the incident.

- Intelligence Support and related activities include intelligence collection in support of investigative activities, and integrated analysis of threat trends and events to build situational awareness and to identify knowledge gaps, as well as the ability to degrade or mitigate adversary threat capabilities. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence, through the Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Center, will be the Federal lead agency for intelligence support and related activities.

In addition to these lines of effort, a victim will undertake a wide variety of response activities in order to maintain business or operational continuity in the event of a cyber incident. We recognize that for the victim, these activities may well be the most important. Such efforts can include communications with customers and the workforce; engagement with stakeholders, regulators, or oversight bodies; and recovery and reconstitution efforts. When a Federal agency is a victim of a significant cyber incident, that agency will be the lead for this fourth line of effort. In the case of a private victim, the Federal government typically will not play a role in this line of effort, but will remain cognizant of the victim’s response activities consistent with these principles and coordinate with the victim.

Coordination Architecture

In order to facilitate the more coordinated, integrated response demanded by significant cyber incidents, the PPD establishes a three-tiered coordination architecture for handling those incidents:

National Policy Level: The PPD institutionalizes the National Security Council-chaired interagency Cyber Response Group (CRG). The CRG will coordinate the development and implementation of United States Government policy and strategy with respect to significant cyber incidents affecting the United States or its interests abroad.

National Operational Level: The PPD directs agencies to take two actions at the national operational level in the event of a significant cyber incident.

- Activate enhanced internal coordination procedures. The PPD instructs agencies that regularly participate in the Cyber Response Group to develop these procedures to ensure that they can surge effectively when confronted with an incident that exceeds their day-to-day operational capacity.

- Create a Unified Coordination Group. In the event of a significant cyber incident, the PPD provides that the lead agencies for each line of effort, along with relevant Sector-Specific Agencies (SSAs), state, local, tribal and territorial governments, international counterparts, and private sector entities, will form a Cyber Unified Coordination Group (UCG) to coordinate response activities. The Cyber UCG shall coordinate the development, prioritization, and execution of cyber response efforts, facilitate rapid information sharing among UCG members, and coordinate communications with stakeholders, including the victim entity.

Field Level: The PPD directs the lead agencies for each line of effort to coordinate their interaction with each other and with the affected entity.

Integration with Existing Response Policy

The PPD also integrates U.S. cyber incident coordination policy with key aspects of existing Federal preparedness policy to ensure that the Nation will be ready to manage incidents that include both cyber and physical effects, such as a significant power outage resulting from malicious cyber activity. The PPD will be implemented by the Federal government consistent with existing preparedness and response efforts.

Implementation tasks

The PPD also directs several follow-on tasks in order to ensure its full implementation. In particular, it requires that the Administration develop and finalize the National Cyber Incident Response Plan – in coordination with State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal governments, the private sector, and the public – to further detail how the government will manage cyber incidents affecting critical infrastructure. It also directs DHS and DOJ to develop a concept of operations for how a Cyber UCG will operate and for the NSC to update the charter for the CRG.