Washington, D.C.

Woodrow Wilson Center

(As delivered)

Good morning everyone. Thank you Jane and the Wilson Center for hosting me again for this annual ritual. Jane is a terrific supporter of our Department and our homeland security mission, and a voice of strength and common sense in this town. Jane, for the third year in a row, I continue to appreciate your leadership and mentorship. Thank you again.

Today I will outline progress we made in 2015 and the goals the President and I have for the Department of Homeland Security in 2016. In the remaining 344 days of this Administration, there is much to do. I intend to make every day count. The former president of my alma mater, Morehouse College, used to tell his students we only have just a minute, but eternity is in it, and it’s up to us to use it. With Deputy Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas as my partner, we will push an aggressive agenda to the end.

I begin these remarks with a shout-out to the men and women of DHS, led by the terrific component heads seated before me. It’s the nature of our business in homeland security that no news is good news. But no news is very often the product of the hard work and extraordinary, courageous effort our people put in every day to keep the American public safe.

Last fiscal year, for example, TSA screened 695 million passengers (3 million more than the year before); screened 450 million pieces of checked luggage (the highest in six years), and, at the same time, seized a record number 2,500 firearms from carry-on luggage, 84 percent of which were loaded.

Last fiscal year CBP screened 26.3 million containers, 11.3 million commercial trucks, 1 million commercial and private aircraft, 436,000 buses, ferries and trains, 103 million private vehicles, and 382 million travelers at land, marine and air ports of entry to the United States. At the same time, CBP collected nearly $46 billion in duties, taxes, and fees, making it the second largest revenue collector in the U.S. government.

Last fiscal year, HSI made a record high 33,000 criminal arrests, including 3,500 alleged members of transnational criminal gangs, and 2,400 alleged child predators.

Last fiscal year the Coast Guard saved over 3,500 lives, and seized 319,000 pounds of cocaine and 78,000 pounds of marijuana worth a total of $4.3 billion wholesale. In just one mission off the coast of Central and South America, the National Security Cutter STRATTON alone seized over $1 billion in cocaine, along with two drug cartel-owned submersibles.

Last year the Secret Service successfully orchestrated what may have been the largest domestic security operation in the history of this country, by providing physical security to 160 world leaders at the UN General Assembly, and, at the same time, providing security for Pope Francis as he visited New York, Washington, and Philadelphia.

Last year FEMA provided over $6 billion in federal disaster assistance, and was there to help communities recovering from flooding in Texas and South Carolina, tornadoes in Oklahoma, and typhoons in the Western Pacific.

This past Sunday, DHS personnel from the Secret Service, TSA, CBP, HSI, FEMA, I&A, NPPD, the Coast Guard, and other components led the federal effort to provide ground, air, maritime and cyber security for Super Bowl 50.

Then there are the individual acts of good and heroic work by our people, to save lives and go above and beyond the call of duty.

In late December nine Border Patrol agents traveled miles on foot or by horseback to come to the aid of an Arizona rancher who had fallen off her horse in a remote, mountainous area.

Last March two uniformed Secret Service officers helped save the life of a journalist who suffered a heart attack in the East Room of the White House.

Last July Coast Guard Petty Officer Darren Harrity swam nearly a mile, at night, in 57-degree water and 30-mph winds, to save the lives of four stranded fishermen.

Finally, we honor those killed in the line of duty. HSI Agent Scott McGuire was killed last month by a hit and run driver in Miami. I was glad to at least have had the opportunity to visit with Scott’s wife and five-year-old son, and hold Scott’s hand before he was officially declared brain dead. His funeral was 10 days ago in New Orleans.

Our people do extraordinary work every day to protect the homeland. Please consider thanking a TSO, a Coastie, a Customs officer, or a Border agent next time you see one.

Management Reform

Though our people do extraordinary work, I know we must improve the manner in which the Department conducts business. Like last year, reforming the way in which the Department of Homeland Security functions, to more effectively and efficiently deliver our services to the American people, is my New Year’s resolution for 2016. We’ve done a lot in the last two years, but, under the leadership of our Under Secretary for Management Russ Deyo, there is still much we will do.

My overarching goal as Secretary this last year is to continue to protect the homeland, and leave the Department of Homeland Security a better place than I found it.

The centerpiece of our management reform has been the Unity of Effort initiative I announced in April 2014, which focuses on getting away from the stove pipes, in favor of more centralized programming, budgeting, and acquisition processes.

We have transformed our approach to the budget. Today, we focus Department-wide on our mission needs, rather than through component stove pipes. With the support of Congress, we are moving to a simplified budget structure, in which line items mean the same across all components.

We have transformed our approach to acquisition. Last year I established a DHS-wide Joint Requirements Council to evaluate, from the viewpoint of the Department as a whole, our components’ needs on the front end of an acquisition.

We have launched the “Acquisition Innovations in Motion” initiative, to consult with the contractor community about ways to improve the quality and timeliness of our contracting process, and the emerging skills required of our acquisition professionals. We are putting faster contracting processes in place.

We are reforming our HR process. We are making our hiring process faster and more efficient. We are using all the tools we have to recruit, retain and reward personnel.

As part of the Unity of Effort initiative, in 2014 we created the Joint Task Forces dedicated to border security along the southern border. Once again, we are getting away from the stove pipes. In 2015, these Task Forces became fully operational. In 2016, we are asking Congress to officially authorize them in legislation.

We are achieving more transparency in our operations. We have staffed up our Office of Immigration Statistics and gave it the mandate to integrate immigration data across the Department. Last year, and for the second year in a row, we reported our total number of repatriations, returns and removals on a consolidated, Department-wide basis.

The long-awaited entry/exit overstay report was published in January, providing a clearer picture of the number of individuals in this country who overstay their visitor visas. It reflects that about one percent of those who enter this country by air or sea on visitor visas or through the Visa Waiver Program overstay.

We are working with outside, non-partisan experts on a project called BORDERSTAT, to develop a clear and comprehensive set of outcome metrics for measuring border security, apprehension rates, and inflow rates.

Since 2013 we’ve spearheaded something called the “DHS Data Framework” initiative. For the protection of the homeland, we are improving the collection and comparison of travel, immigration and other information against classified intelligence. We will do this consistent with laws and policies that protect privacy and civil liberties.

As we have proposed to Congress, I want to restructure the National Protection and Programs Directorate from a headquarters element to an operational component called the “Cyber and Infrastructure Protection” Agency.

I am very pleased with the 2016 DHS budget adopted by Congress and signed by the President as part of the omnibus spending deal reached in December. I’m very pleased with that. It funds all of our homeland security priorities, including, finally, the completion of the main building of the new DHS headquarters at St. Elizabeths campus in SE Washington. I will never get to work there, but perhaps they will name a courtyard or conference room after me.

The President’s budget request for 2017, released two days ago, funds our key priorities, to include aviation security, the Secret Service, recapitalization of the Coast Guard, and provides a huge increase in funding for cybersecurity.

Finally, we will improve the levels of employee satisfaction across the Department. We’ve been on an aggressive campaign to improve morale over the last two years. It takes time to turn a 22-component workforce of 240,000 people in a different direction. Though the overall results last year were still disappointing, we see signs of improvement. Employee satisfaction improved in a number of components, including at DHS headquarters.

This year we will see an improvement in employee satisfaction across DHS.

Counterterrorism

In 2016, counterterrorism will remain the cornerstone of the Department of Homeland Security’s mission. The events of 2015 reinforce this.

As I have said many times, we are in a new phase in the global terrorist threat, requiring a whole new type of response. We have moved from a world of terrorist directed attacks to a world that includes the threat of terrorist inspired attacks – in which the terrorist may have never come face to face with a single member of a terrorist organization, lives among us in the homeland, and self-radicalizes, inspired by something on the internet.

By their nature, terrorist-inspired attacks are harder to detect by our intelligence and law enforcement communities, could occur with little or no notice, and in general makes for a more complex homeland security challenge.

So, what are we doing about this?

First, our government, along with our coalition partners, continues to take the fight militarily to terrorist organizations overseas. ISIL is the terrorist organization most prominent on the world stage. Since September 2014, air strikes and special operations have in fact led to the death of a number of ISIL’s leaders and those focused on plotting external attacks in the West. At the same time, ISIL has lost about 40 percent of the populated areas it once controlled in Iraq, and thousands of square miles of territory it once controlled in Syria.

On the law enforcement side, the FBI continues to do an excellent job of detecting, investigating, preventing, and prosecuting terrorist plots here in the homeland.

As for the Department of Homeland Security, following the attacks in Ottawa, Canada in 2014, and in reaction to terrorist groups’ public calls for attacks on government installations in the western world, I directed our Federal Protective Service to enhance its presence and security at various U.S. government buildings around the country.

Given the prospect of the terrorist-inspired attack in the homeland, we have intensified our work with state and local law enforcement. Almost every day, DHS and the FBI share intelligence and information with Joint Terrorism Task Forces, fusion centers, local police chiefs and sheriffs.

In FY 2015 we provided over $2 billion in homeland security assistance to state and local governments around the country, for things such as active shooter training exercises, overtime for cops and firefighters, salaries for emergency managers, emergency vehicles, and communications and surveillance equipment. We helped to fund an active shooter training exercise that took place in the New York City subways last November and a series of these exercises just last weekend in Miami, Florida.

As I said at a graduation ceremony for 1,200 new cops in New York City in December, given the current threat environment, it is the cop on the beat who may be the first to detect the next terrorist attack in the United States.

We are enhancing information sharing with organizations that represent businesses, college and professional sports, faith-based organizations, and critical infrastructure.

We are enhancing measures to detect and prevent travel to this country by foreign terrorist fighters.

We are strengthening our Visa Waiver Program, which permits travelers from 38 different countries to come here without a visa. In 2014, we began to collect more personal information in the Electronic System for Travel Authorization, also known as the “ESTA” system, that travelers from Visa Waiver countries are required to use. As a result of these enhancements, over 3,000 additional travelers were denied travel here in FY 2015.

In August 2015, we introduced further security enhancements to the Visa Waiver Program.

Through the passage in December of the Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act of 2015, Congress has codified into law several of these security enhancements, and placed new restrictions on eligibility for travel to the U.S. without a visa. We began to enforce these new restrictions on January 21. Waivers from these restrictions will only be granted on a case-by-case basis, when it is in the law enforcement or national security interests of the United States to do so. Those denied entry under the Visa Waiver Program as a result of this new law may still apply for a visa to travel to the U.S.

We are expanding the Department’s use of social media for various purposes. Today social media is used for over 33 different operational and investigative purposes within DHS. Beginning in 2014 we launched four pilot programs that involved consulting the social media of applicants for certain immigration benefits. USCIS now also reviews the social media of Syrian refugee applicants referred for enhanced vetting. Based upon the recent recommendation of a Social Media Task Force within DHS, I have determined that we must expand the use of social media even further, consistent with law.

CBP is deploying our Customs personnel at various airports abroad, to pre-clear air travelers before they get on flights to the United States. At present, we have this pre-clearance capability at 15 airports overseas. And, last year, through pre-clearance, we denied boarding to over 10,700 travelers (or 29 per day) seeking to enter the United States. As I said here last year, we want to build more of these. In May 2015, I announced 10 additional airports in nine countries that we’ve prioritized for preclearance.

For years Congress and others have urged us to develop a system of biometric exit – that is, to take the fingerprints or other biometric data of those who leave the country. CBP has begun testing technologies that can be deployed for this nationwide. With the passage of the omnibus bill, Congress authorized $1 billion in fee increases over a period of ten years to pay for the implementation of biometric exit. I have directed CBP begin implementing the system, starting at airports, in 2018.

Last month I announced the schedule for the final two phases of implementation of the REAL ID law, which goes into effect two and then four years from now. At present 23 states are compliant with this law, 27 have extensions, and 6 states or territories are out of compliance. Now that the final timetable for implementation of this law is in place, we will urge all states, for the good of their residents, to start issuing REAL ID-complaint drivers’ licenses as soon as possible.

In the current threat environment, there is a role for the public too. “If You See Something, Say Something™” must be more than a slogan. We continue to stress this. DHS has now established partnerships with the NFL, Major League Baseball and NASCAR, to raise public awareness at sporting events. An informed and vigilant public contributes to national security.

In December we reformed “NTAS,” the National Terrorism Advisory System. In 2011, we replaced the color-coded alerts with NTAS. But, the problem with NTAS was we never used it. It consisted of just two types of Alerts: “Elevated” and “Imminent,” and depended on the presence of a known specific and credible threat. This does not work in the current environment, which includes the threat of homegrown, self-radicalized, terrorist-inspired attacks.

So, in December we added a new form of advisory – the NTAS “Bulletin” – to the existing Alerts. The Bulletin we issued in December advises the public of the current threat environment, and how the public can help.

Finally, given the nature of the evolving terrorist threat, building bridges to diverse communities has become a homeland security imperative. Well informed families and communities are the best defense against terrorist ideologies. Al Qaeda and the Islamic State are targeting Muslim communities in this country. We must respond. In my view, this is as important as any of our other homeland security missions.

In 2015 we took these efforts to new levels. We created the DHS Office for Community Partnerships, headed by George Selim. George and this office are now the central hub of the Department’s efforts to counter violent extremism in this country, and the lead for a new interagency CVE Task Force that includes DHS, DOJ, the FBI, NCTC and other agencies.

Aviation Security

We are taking aggressive steps to improve aviation and airport security. The traveling public should be aware that, because of this and increased traveler volume, overall wait times have increased somewhat at airports, but we believe this is necessary for the public’s own safety.

Since 2014 we have enhanced security at overseas last-point-of-departure airports, and a number of foreign governments have replicated these enhancements.

As many of you know, in May of last year a certain classified DHS Inspector General’s test of TSA screening at eight airports, reflected a dismal fail rate and was leaked to the press. I directed a 10-point plan to fix the problems identified by the IG. Under the new leadership of Admiral Pete Neffenger over the last six months, TSA has aggressively implemented this plan. This has included “back to basics” retraining of the entire TSO force, increased use of random explosive trace detectors, testing and re-evaluating the screening equipment that was the subject of the IG’s test, a rewrite of the standard operating procedures manual, increased manual screening, and less managed inclusion. These measures were implemented on or ahead of schedule.

We are also focused on airport security. In April of last year TSA issued guidelines to domestic airports to reduce access to secure areas, to require that all airport and airline personnel pass through TSA screening if they board a flight, to conduct more frequent screening of airport and airline personnel, and to conduct continuous criminal background checks of airport and airline personnel. Since then employee access points have been reduced, and random screening of personnel within secure areas has increased four-fold. We are continuing these efforts in 2016. Two days ago TSA issued guidelines to further enhance the screening of aviation workers in the secure area of airports.

Cybersecurity

While counterterrorism remains a cornerstone of our Department’s mission, I have concluded that cybersecurity must be another. Making tangible improvements to our Nation’s cybersecurity is a top priority for me and President Obama before we leave office.

Two days ago the President announced his “Cybersecurity National Action Plan,” which is the culmination of seven years of effort by his Administration. The Plan includes a call for the creation of a Commission on Enhancing National Cybersecurity, additional investments in technology, federal cybersecurity, cyber education, new cyber talent in the federal workforce, and improved cyber incident response.

DHS has a role in almost every aspect of this plan.

As reflected in the President’s 2017 budget request, we want to expand our cyber response teams from 10 to 48.

We are doubling the number of cybersecurity advisors to in effect make “house calls,” to assist private sector organizations with in-person, customized cybersecurity assessments and best practices.

Building on DHS’s Stop.Think.Connect campaign, we will help promote public awareness on multi-factor authentication.

We will collaborate with Underwriters Laboratory and others to develop a Cybersecurity Assurance Program to test and certify networked devices within the “Internet of Things” — such as your home alarm system, your refrigerator, or even your pacemaker.

Last year we greatly expanded the capability of DHS’s National Cybersecurity Communications Integration Center, or “NCCIC.” The NCCIC increased its distribution of information, the number of vulnerability assessments conducted, and the number of incident responses.

At the NCCIC, last year we built a system to automate the receipt and distribution of cyber threat indicators in near real-time speed. We built this in a way that also includes privacy protections. We did this ahead of schedule.

I have issued an aggressive timetable for improving federal civilian cybersecurity, principally through two DHS programs:

The first is called EINSTEIN. EINSTEIN 1 and 2 have the ability to detect and monitor cybersecurity threats in our federal civilian systems, and are now in place across all federal civilian departments and agencies.

EINSTEIN 3A is the newest iteration of the system, and has the ability to actually block potential cyber attacks on our federal systems. Thus far E3A has actually blocked 700,000 cyber threats, and we are rapidly expanding this capability. About a year ago, E3A covered only about 20 percent of our federal civilian networks. In the wake of the OPM attack, in May of last year I directed our cybersecurity team to make at least some aspects of E3A available to all federal departments and agencies by the end of last year. They met that deadline. Now that the system is available to everyone, 50 percent are actually on line, including OPM, and we are working to get all federal departments and agencies on board by the end of this year.

The second program, called Continuous Diagnostics and Mitigation, helps agencies detect and prioritize vulnerabilities in their networks. In 2015, we provided CDM sensors to 97 percent of the federal civilian government. Next year, DHS will provide the second phase of CDM to 100 percent of the federal civilian government.

We have worked with OMB and DNI to identify the government’s high value systems, and we are working aggressively with the owners of these systems to increase their security.

In September, DHS awarded a grant to the University of Texas San Antonio to work with industry to identify a common set of best practices for the development of Information Sharing and Analysis Organizations, or “ISAOs.”

Finally, I thank Congress for passing the Cybersecurity Act of 2015. This new law is a huge assist to DHS and our cybersecurity mission. We are in the process of implementing this new law now.

Immigration/Border Security

Turning to immigration and border security:

As I explain it to both Democrats and Republicans, immigration policy must be two sides of the same coin. The resources we have to enforce immigration laws are finite, and they must be used wisely. This is true of every aspect of law enforcement. It’s referred to as “prosecutorial discretion.”

With the immigration enforcement resources we have, ICE is focused more sharply on public safety and border security. Those who are convicted of serious crimes or who are apprehended at the border are top priorities for removal. And we will enforce the law in accordance with these priorities.

Accordingly, over the last several years deportations by ICE have gone down, but an increasing percentage of those deported are convicted criminals. And, an increased percentage of those in immigration detention, around 85 percent, are in the top priority for removal. We will continue to focus our resources on the most significant threats to public safety and border security.

In furtherance of our public safety efforts, in 2014 we did away with the controversial Secure Communities program and replaced it with the new Priority Enforcement Program, or “PEP.” PEP fixes the political and legal controversies, in my judgment, associated with Secure Communities and enables us to take directly into custody from local law enforcement the most dangerous, removable criminals. Since PEP was created, cities and counties that previously refused to work with Secure Communities are coming back to the table. Of the 25 largest counties that refused to work with ICE before, 16 are now participating in PEP. In 2016, we want to get more to participate.

And, because we are asking ICE immigration enforcement officers to focus on convicted criminals and do a job that’s more in line with law enforcement, last year we reformed their pay scale accordingly. Now these immigration officers are paid on the same scale as the rest of federal law enforcement.

We have also prioritized the removal of those apprehended at the border. We cannot allow our borders to be open to illegal migration.

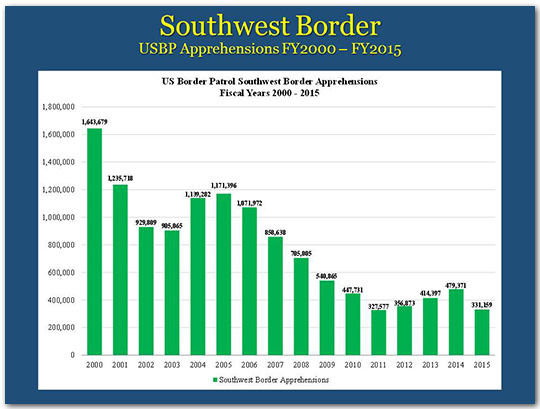

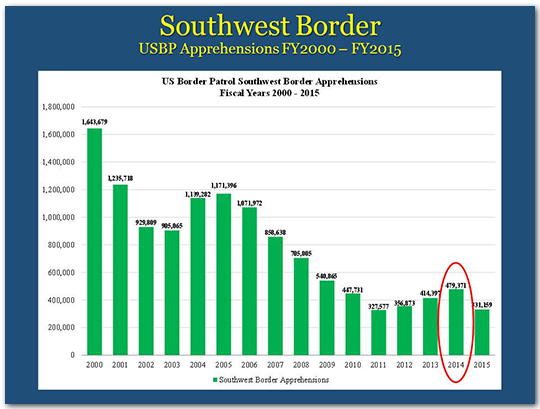

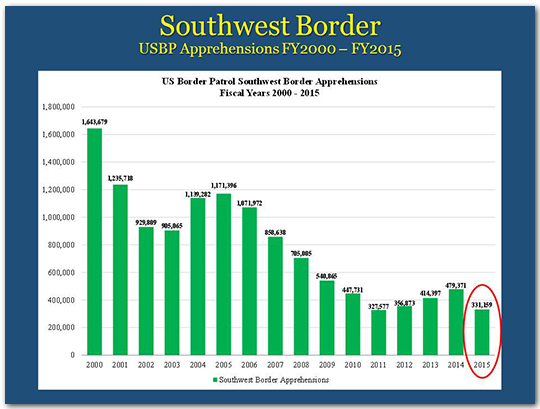

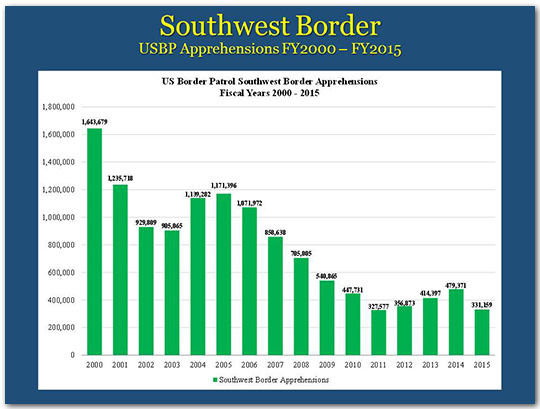

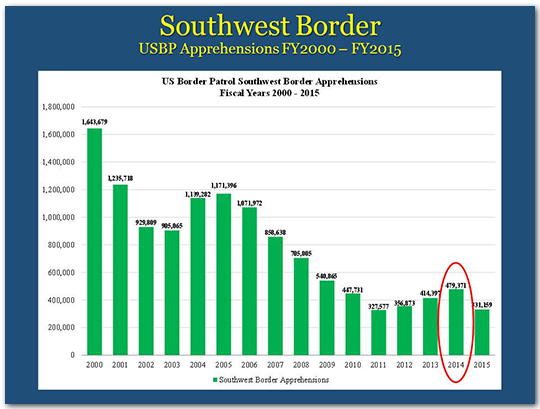

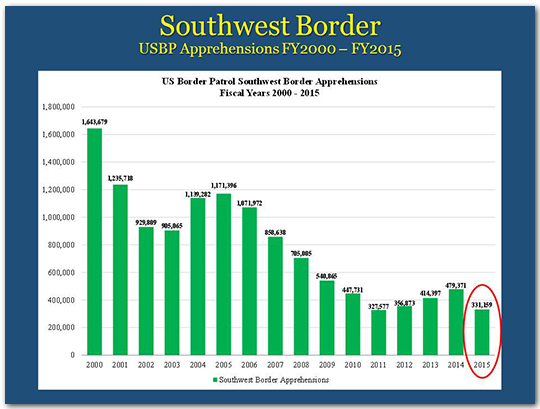

Over the last 15 years, our Nation – across multiple administrations — has invested a lot in border security, and this investment has yielded positive results. Apprehensions – which are an indicator of total attempts to cross the border illegally – are a fraction of what they used to be.

In FY 2014, overall apprehensions increased, as we saw a spike in the number of families and unaccompanied children from Central America during the spring and summer of 2014. That year the overall number of apprehensions was 479,000. Across the government, we responded aggressively to this surge and the numbers fell sharply within a short period of time.

In FY 2015, the number of those apprehended on the southwest border was 331,000 – with the exception of one year, this was the lowest number since 1972.

From July to December 2015 the numbers of migrants from Central America began to climb again.

In January I announced a series of focused enforcement actions to take into custody and remove those who had been apprehended at the border in 2014 or later and then ordered removed by an immigration court. I know this made a lot of people I respect very unhappy. But, as I said, we must respect the law in accordance with our priorities and enforce it.

In January overall apprehensions on the southwest border dropped 36 percent from the month before. At the same time, the number of unaccompanied children apprehended dropped 54 percent, and the number of those in families dropped 65 percent. So far in February, the numbers have remained at this decreased level. This six-week decline is encouraging, but it does not mean we can dial back our efforts. We will continue to enforce the law consistent with our priorities for enforcement, which includes those apprehended at the border in 2014 or later.

Then there is the other side of the coin. The new enforcement policy the President and I announced in November 2014 makes clear that our limited resources will not be focused on the removal of those who have committed no serious crimes, have been in this country for years, and have families here. Under our new policy, these people are not priorities for removal, nor should they be.

In fact, the President and I want to offer, to those who have lived here for at least five years, are parents of U.S. citizens or lawful permanents residents, and who have committed no serious crimes, the opportunity to request deferred action on a case-by-case basis, to come out of the shadows, get on the books, and be held accountable. We are pleased that the Supreme Court has agreed to hear the case of Texas v. United States, which involves the new deferred action policies we announced in November 2014.

Our immigration enforcement priorities, the ending of Secure Communities, and the new deferred action policy now in the courts are among 10 executive actions the President and I announced in November 2014 to fix our broken immigration system.

We also issued a proposed rule to expand eligibility for “provisional” extreme hardship waivers of the 3- and 10-year bars to all persons who statutorily qualify for a waiver. The comment period is closed, and we are now preparing to issue the final rule on provisional waivers.

We published new guidance for public comment on the “extreme hardship” requirement. The comment period is closed and we plan to issue final guidance on extreme hardship very soon.

We are about to publish a final rule to strengthen the program that provides Optional Practical Training for students in STEM fields studying at U.S. universities.

We finalized a new rule that allows spouses of high-skilled H-1B workers who are here in the United States under H-4 visas to apply for work authorization.

We are working with the Department of Labor and other agencies to ensure, for the protection of workers, the consistent enforcement of federal labor, employment and immigration laws.

We are promoting and increasing access to citizenship through the new White House Task Force on New Americans. The week of September 14-21 we celebrated the “Stand Stronger Commit to Citizenship Campaign.” In that one week, USCIS naturalized 40,000 people.

We now permit credit cards as a payment option for naturalization fees.

Our overall policy is to focus our immigration resources more effectively on threats to public safety and border security, and, within our existing legal authority, do as much as we can to fix the broken immigration system. We’re disappointed that Congress has not been our partner in this effort, by passing comprehensive immigration reform legislation.

Finally, we recognize that more border security and deportations may deter illegal migration, but they do nothing to overcome the “push factors” that prompt desperate people to flee Central America in the first place. We are preparing to offer vulnerable individuals fleeing the violence in Central America a safe and legal alternate path to a better life. We are expanding our Refugee Admissions Program to help vulnerable men, women and children in Central America who qualify as refugees. We are partnering with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and non-governmental organizations in the region to do this as soon as possible. This approach builds on our recently established Central American Minors program, which is now providing an in-country refugee processing option for certain children with lawfully present parents in the United States.

Refugees

We are doing our part to address the Syrian refugee crisis. USCIS, in conjunction with the Department of State, is working hard to meet our commitment to admit at least 10,000 Syrian refugees by the end of this fiscal year. We will do this carefully, screening refugees in a multi-layered and intense screening process involving multiple law enforcement, national security, and intelligence agencies across the Federal Government.

U.S. Secret Service

Over the last year, Director Joe Clancy of the Secret Service has done a tremendous job reforming his agency, including hiring a chief operating officer from outside the Secret Service, altering the structure and management of the agency, ramping up efforts to hire new members of its workforce, and expanding training opportunities. In 2016 we will continue to work on areas that still need improvement.

The U.S. Coast Guard

With the help of Congress, in 2016 we will continue to rebuild the Coast Guard fleet. This year Congress provided funding for a ninth National Security Cutter, design funding for the Offshore Patrol Cutter, and funding to continue production of our Fast Response Cutter. As reflected in the President’s 2017 Budget Request, we will also seek $150 million for the design of a new heavy icebreaker, in recognition of the expanding commercial activity in the Arctic.

FLETC

Since 2012, our Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC) has trained more than a quarter million federal, state and local officers and agents. At the same time, FLETC continually updates its curriculum to address the biggest challenges facing law enforcement, to include training for active shooter situations, in cyber forensics, and in human trafficking.

FEMA

In 2016 FEMA will continue to do its extraordinary job of supporting the American people and communities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from various disasters. FEMA will continue to focus on efforts to enhance resilience and mitigation measures before disaster strikes, to prevent loss and save lives.

Lawful Trade and Travel

We continue to promote lawful trade and travel. We will continue to pursue the President’s U.S.-Mexico High Level Economic Dialogue and his Beyond the Border Initiative with Canada. We are implementing the “Single Window,” which, by December 2016, will enable the private sector to use just one portal to transmit information to 47 government agencies about exports and imports, thereby eliminating over 200 different forms and streamlining the trade process.

Last week the Secretary of Commerce and I joined the President of Mexico to open a new six-lane bridge near El Paso that will replace a 78-year-old two-lane one. Next week I will join the Mexican Secretary of Finance to inaugurate a pre-inspection pilot in Laredo, Texas.

Conclusion

In conclusion, according to Time Magazine, I have “probably the hardest job in America.” That’s not true. The President has the hardest job in America. But I may rank in the top ten. I have a lot of challenges, a lot of problems and a lot of headaches. There is also far too much partisanship in Washington, and, especially during an election year, politics has become a blood-sport in this town. Too often it is more important to score political points than achieve smart, sound government policy on behalf of the American people.

Through it all, I still love public service, and I am dedicated to serving the American people, protecting our homeland, and serving our President.

I find inspiration in the amazing stories of our workforce that I told you about at the beginning of this speech. I also find inspiration and strength in the weekly batch of letters I receive from the American people we serve, particularly from the school kids. Here’s one from a young man named Brett Shepard, handwritten in pencil:

“To Jeh Johnson…I just wanted to say I think you’re doing a good job… I ran for class president in my government class. I ended up becoming the Secretary of Homeland Security which honestly I would rather be … [president is] not all it’s cracked up to be.”

Like Brett, at this moment in the life of our Nation, there’s nothing I’d rather be than Secretary of Homeland Security. It is and always will be the highlight of my professional life. In the time left to me in office, I pledge all my energy to continue to protect the homeland and leave the Department of Homeland Security a better place than I found it.

Thank you very much.