Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) freed 36,007 convicted criminal aliens from detention who were awaiting the outcome of deportation proceedings. The group included aliens convicted of hundreds of violent and serious crimes, including homicide, sexual assault, kidnapping, and aggravated assault. The list of crimes also includes more than 16,000 drunk or drugged driving convictions. Since many had committed multiple crimes, the 36,007 aliens had nearly 88,000 convictions among them.

In response to the report, the Obama administration claimed that some of the releases were mandated by a Supreme Court ruling from 2001.1 The central case is Zadvydas v. Davis, which held that the federal government can detain aliens for deportation up to six months, but generally must release them back into the United States after that point if there is “no significant likelihood of removal in the reasonably foreseeable future”. One of the main reasons such a situation arises is that a criminal alien’s home country will refuse to take its nationals back. Instead of demanding that countries cooperate, the White House simply let thousands of criminal aliens go free. Vaughan estimates around 3,000 releases were based on this ruling. A spokesperson for ICE claimed that “mandatory releases account for over 72% of the homicides listed”.

Read more here, PLEASE.

Below is a handful of cases where the threat became reality.

Many freed criminals avoid deportation, strike again

FLUSHING, N.Y. — Qian Wu thought the man who brutally attacked her was gone forever.

She was sure that Huang Chen, a Chinese citizen who slipped into America on a ship and stayed in the country illegally, would be deported as soon as he got out of jail for choking, punching, and pointing a knife at her in 2006.

But China refused to take Chen back. So, after jailing Chen on and off for three years in Texas, immigration officials believed they were out of options and did what they have done with thousands of criminals like him.

They quietly let him go.

Nobody warned Wu, or prosecutors, or the public. The petite, 46-year-old woman learned Chen was still here when he stormed into her unlocked apartment one day in January 2010 and announced, “I bet you didn’t expect to see me.” Terrified, she called the police, and he fled. But for two weeks, Chen was free to stalk her and finally, to catch her as she hurried home with milk and bread one afternoon.

Chen then finished what he had started earlier, bashing Wu on the head with a hammer and slashing her with a knife. As she lay crumpled in a grimy stairwell, he ripped out her heart and a lung and fled with his macabre trophies.

“She lived in horror in the last two weeks of her life,” said Yongwei Guo, Wu’s widower, through an interpreter in New York. “She knew there was somebody coming to kill her and we asked the police for protection, and also the government, but they did nothing.”

Yongwei Guo’s wife was killed in 2010 by a criminal who had been released by immigration officials.

Wu is just one casualty of an immigration system cloaked in a blanket of secrecy that the Founding Fathers could not have imagined, a blanket that isn’t lifted even when life is at risk. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and its sister agencies have emerged as the largest law enforcement network in the United States since the Sept. 11 terror attacks, and they are increasingly dealing with criminals, but they play by very different rules than the local police, prosecutors, or even the FBI.

A yearlong Globe investigation found the culture of secrecy can be deadly to Americans and foreigners alike: Immigration officials do not notify most crime victims when they release a criminal such as Chen, and they only notify local law enforcement on a case by case basis. And even though immigration officials have the power to try to hold dangerous people longer, that rarely occurs.

The Globe also found that the pattern of secrecy extends to the treatment of immigrants who end up behind bars, though they have no criminal records. Foreigners in immigration detention have fewer rights than ordinary criminal suspects and limited ability to get word to the outside world about their plight. Even their names are kept secret, purportedly for their own protection, and many never get a public hearing to make their case.

Taken together, the system produces a litany of consequences: A young Lynn woman with no criminal record died in immigration custody from a heart ailment without a chance to ask a judge for medical help; a father of five in Texas disappeared from his family for several days after he was detained; a Cuban man in a wheelchair languished for an extraordinary 14 years in immigration detention, invisible to the world outside.

It is also a system in which — as Wu would learn in her final days of terror — Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, routinely releases dangerous detainees to the streets of America without warning the public. Over the past four years, immigration officials have largely without notice freed more than 8,500 detainees convicted of murder, rape, and other crimes, according to ICE’s own statistics, mainly because their home countries would not take them back.

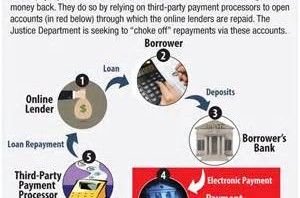

Deporting illegal immigrants requires more than simply putting them on an airplane to their own country. People being deported need travel papers — such as a passport — like anyone else who travels abroad. If their native country refuses to issue the necessary papers , the United States cannot send deportees there. And the Supreme Court has said ICE cannot hold the immigrants forever; if immigration officials cannot deport them after six months, the court said, they should generally set the immigrants free.

When the Globe requested the names of the released criminals under the Freedom of Information Act, federal immigration officials refused, saying it would be a “clearly unwarranted invasion” of the immigrants’ privacy. Officials said public interest in their names was “minimal” anyway.

“In the absence of any identified public interest or explanation as to how the disclosure of the arrestees’ information will advance that interest, the personal privacy interests will prevail,” Matthew Chandler, spokesman for the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees immigration, said in a written statement to the Globe.

But a disturbing number of foreigners have been arrested after their release, including some for heinous crimes. Abel Arango, an armed robber who was released when his native Cuba wouldn’t take him back, shot and killed a Fort Myers, Fla., police officer who responded to a report of a loud fight between Arango and his girlfriend in 2008. Binh Thai Luc, an armed robber from Vietnam, couldn’t be deported either, so he was released. In March, he allegedly massacred five people in a San Francisco home.

McCarthy Larngar, a Liberian national who served several years in prison for shooting and wounding a man in Rhode Island, was released in 2007 when Liberia would not take him back — even though a Boston immigration official had described him in court records as “a danger to the community.” After multiple brushes with the law, Larngar was arrested last year and charged with tying up and robbing a man and a woman in a bizarre kidnapping in Pawtucket. His lawyer said in court documents that he is not guilty, and he is now in a Rhode Island jail on a violation from an earlier crime.

In New England, immigration officials have released as many as 10 convicted murderers since 2008.

They include Hung Truong, a robber who repeatedly stabbed a bound and gagged 15-year-old Everett girl during a 1989 kidnapping that left the girl and her mother dead. Massachusetts released Truong on parole about 20 years into his life prison sentence in hopes that he would be deported to his native Vietnam in 2010. But ICE could not deport him because Vietnam has refused to accept deportees who came to the United States before 1995. Now, he’s back in prison after failing a drug test that was part of his release deal with the state Parole Board.

As part of its investigation, the Globe filed more than 20 different public records requests to obtain more detailed information about the people held — and released — by the immigration system. Many requests were rejected or the responses were heavily censored, prompting the Globe to file a lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security in November. But this much is clear from the available documents: Federal officials are releasing people that they regard as dangerous and doing little to force recalcitrant countries to take their citizens back.

More than 20 governments from Jamaica to China routinely block deportation of their citizens, even dodging calls from US immigration officers seeking to expedite the process, and critics say they suffer few consequences. Some, such as US Representative Ted Poe, a Texas Republican, argue that the United States should stop accepting diplomats from countries who do not repatriate their citizens, but the State Department has shown little interest, preferring to work through diplomatic channels to deport immigrants. Federal officials have refused to issue visas to only one nation, tiny Guyana in South America.

Even when foreigners cannot be deported, immigration officials, under a 2001 Supreme Court ruling, could seek to hold them longer on the grounds that they are a danger to the public. Immigration officials say the legal standard for holding an immigrant longer for that reason is very high, limiting their ability to use it. They point out that immigrants are detained for civil immigration violations and not crimes.

But the Globe found that immigration officials almost never try to declare a detainee dangerous: In the past four years, immigration officials have released thousands of criminals, but court officials say they have handled only 13 cases seeking to hold immigrants longer because they are dangerous.

Too dangerous to release

Immigration agent Earl DeLong and his colleagues wasted little time in trying to put Shafiqul Islam on a plane back to his native Bangladesh two years ago. As soon as he finished his prison term in New York for taking pictures of himself sexually abusing a 12-year-old girl when he was 17, immigration agents called the Bangladeshi consulate in Manhattan.

Initially, the Bangladeshis were reassuring and a consular official, Mamunur Rashid, said he sent the agent’s request for clearance to deport Islam to authorities in Dhaka. But as time dragged on, the cooperation waned.

Whenever DeLong and others called the consulate over the next few months, Rashid was increasingly unavailable. The receptionist said he was not in. He was on vacation or out to lunch. Sometimes, a person at the consulate answered the phone and just hung up. Other times, the phone rang but nobody answered.

“Spoke to a person at the consulate four different times, never able to speak with Mamunur Rashid,” one agent wrote in a secret federal log that became public as part of a lawsuit.

US officials had seen stalling tactics from Bangladesh before: The impoverished Asian nation typically took several months to provide passports for criminals being deported last year — if they provided the documents at all, according to federal statistics.

Foreign countries are understandably reluctant to accept criminals, especially those such as Islam who were raised in the United States, and they have little incentive to do so since the United States rarely takes action against them, such as refusing to issue them visas.

State Department officials acknowledge that they try to avoid reaching the point of sanctions with nations like Bangladesh, but insist that they do apply diplomatic pressure.

“It is a matter we take very seriously, and consistently raise it at high levels with all countries where this is a concern,” said department spokesman Ken Chavez.

Hoping Bangladesh would clear Islam’s return, US immigration officials told Islam in April 2011 that they were going to continue to hold him even though more than six months had passed since Islam’s sexual abuse sentence ended. Islam responded with a lawsuit, charging that immigration could not continue to detain him because it was unlikely that Bangladesh would take him back. In the lawsuit, he pointedly noted that the consulate appeared to be dodging the immigration agent’s calls.

Islam’s lawsuit made public a host of immigration documents that are normally kept secret. The documents revealed both immigration officials’ concerns that Islam is dangerous and their frustrating attempts to contact the Bangladeshis.

But there is no evidence in the file that immigration officials requested an immigration court hearing to determine if they could continue to hold him as a threat to public safety.

Instead, the records show that on Oct. 3, 2011, immigration officials gave up and released Islam.

Seven weeks later, Islam was at Lois Decker’s door.

Everyone loved the retired school lunch lady, a friendly 73-year-old grandmother who taught Sunday school and lived her whole life in Hillsdale, N.Y., a rural hamlet just across the border from the Massachusetts line. Decker raised five children, but she lived alone in the house her daughter bought for her on Cold Water Street.

Sheriff’s deputies say they are unsure what drew Islam to Decker’s house that day, but family members said she had planned to rent out an apartment in the basement. Islam had a construction job in the Berkshires.

Hours after Islam visited Decker’s house, police arrested him in a traffic stop in a nearby city. He had stolen Decker’s white Hyundai, crashed it, and then tried to steal the truck of good Samaritans who had stopped to help him. He finally stole yet another truck, but did not get far. When police arrested him, he was spattered with blood, and had Decker’s credit card in the truck.

Sheriff’s deputies discovered a gruesome scene at Lois Decker’s house. The woman had been strangled, court records showed, and her face and throat were slashed. Officials found Islam’s semen on a sheet in the house, though officials did not find bodily evidence that Decker was sexually assaulted.

Columbia County officials were incensed and demanded to know why ICE had let such a dangerous person go free. They had convicted the high school dropout on sex abuse charges in 2008. Now he’s serving 20 years to life for Decker’s murder.

Paul Czajka, the silver-haired district attorney and a former judge in Columbia County, said immigration officials should have argued that Islam was dangerous enough to hold longer.

He was a child abuser and registered sex offender, therefore by definition he was a danger to the community,” said Czajka. “It would not have been a difficult hearing to make that case.”

But ICE spokesman Ross Feinstein said the agency had little choice but to release criminals such as Islam and Chen because the courts have made it difficult to hold even mentally ill immigrants longer without new criminal charges against them.

“For this reason, the agency’s ability to utilize the continued detention of removable aliens . . . is extremely limited,” Feinstein said.

Lois Decker’s grieving relatives say they’ve been told very little about how Islam gained his release and was able to kill her. Until a Globe reporter contacted the family, they had no idea that Islam had filed a federal lawsuit to get out of jail.

“It’s crazy to me that we don’t know this information,” said Decker’s daughter Diane Demarest, a veterinarian who lives in Oregon.

Some US and Bangladeshi officials involved with Islam’s case did not even realize he had killed Decker until contacted by the Globe.

Gail Y. Mitchell, an assistant US attorney in New York who defended ICE against Islam’s lawsuit to get out of jail, said the case ended because immigration officials released him. She would not say why they didn’t pursue the case and did not know that Islam had gone on to murder Decker.

Bangladesh consul M. Shahedul Islam said he did not know that Islam had killed Decker either. “This guy?” the consul said, raising his eyebrows and pointing to four passport-sized photos of Islam in a file with letters from US immigration officials asking for help with deportation.

The Bangladeshi consulate said Bangladesh did not approve Islam for return because they could not verify he was a citizen of their country.

“We always cooperate with Homeland Security,” said the consul, who is not related to Shafiqul Islam, and he apologized if his staff hung up on ICE agents.

But, for Decker’s family, the conflicting explanations don’t help.

“How could someone not have stopped him along the way?” asked Demarest.

Light sentences for heavy crimes

The uncertainties of the deportation process have another little known effect: Some foreigners get reduced prison sentences when they are convicted of crimes because judges believe they are sure to be deported after their sentence is over. Federal immigration officials warn against the practice, saying that deportation is not a 100 percent certainty even for the worst offender.

No one knows that better than the man Antonino Rodrigues allegedly shot between the eyes this year.

Rodrigues, a convicted drug dealer in the country illegally from Cape Verde, was facing almost four years in federal prison in October 2010 for possessing a stolen, loaded weapon. New Bedford police had caught him: They knew Rodrigues had outstanding arrest warrants and they were pleased when a detective spotted him bar-hopping on the city’s south side.

When Rodrigues appeared for sentencing before US District Judge Douglas P. Woodlock in Boston for the latest in a string of convictions, federal guidelines called for 37 to 46 months in prison.

But defense lawyer Syrie Fried argued that Rodrigues deserved a lighter punishment because he was going to deported anyway. She told the judge Rodrigues had “no prospect of release back into our society.”

Woodlock went along, giving Rodrigues just two years in prison with credit for time served, clearing the way for Rodrigues to finish his prison sentence in March 2011.

“Given the defendant’s near certainty of deportation, the sentence is sufficient but not greater than necessary,” the judge ruled.

But Cape Verde officials did not take Rodrigues back, so immigration officials released him late last year. The Cape Verde consulate in Boston did not respond to questions about why they did not accept Rodrigues.

On June 17, 2012, Rodrigues resurfaced outside an apartment on New Bedford’s Walnut Street, where police say he shot Monzes Goncalves in the forehead with a .22-caliber gun. Goncalves miraculously survived and identified Rodrigues as the shooter.

Rodrigues denied shooting Goncalves and turned himself in to police because he heard they were looking for him.

Fried, the lawyer who helped Rodrigues win a shorter prison sentence in 2010, said she was surprised to learn that her client was still in the United States. She said she did not stay in touch with him because, typically, foreigners who are convicted of serious crimes leave the country.

“I was under the impression . . . that he was going to go straight from serving his jail sentence and be deported,” she said.

The fact is, Rodrigues’ case is not unusual. In Massachusetts over the past four years, the Parole Board has granted early release to 22 immigrants convicted of second-degree murder or manslaughter, several times stating that their willingness to free the prisoner was influenced by his expected departure from the United States. Some prisoners told the board they planned to leave voluntarily for a job in Sierra Leone or a place to live in Cambodia.

However, at least five of the 22 were still here as of July, and, it’s unclear what happened to the other 17. One of the five still here under state supervision is Hung Truong, the Vietnamese national who helped murder an Everett mother and her daughter. Truong had been disciplined more than 30 times in prison, but the board said his behavior had improved — and Truong was possibly leaving anyway.

“It is the judgment of the board that he should be paroled [to federal immigration officials] for possible deportation,” wrote the parole board in its unanimous vote on Sept. 24, 2010.

More than two years later, Truong is still here — in MCI-Shirley, a Massachusetts prison, after flunking a drug test he was required to take as a condition of his release.

No one has to tell Qian Wu’s widower about immigrants getting light sentences for heavy crimes. Yongwei Guo’s wife was killed by an illegal immigrant who prosecutors said was initially sentenced to only 30 days in prison for attacking her the first time. Immigration officials ultimately detained Huang Chen off and on for more than three years in hopes of deporting him, but it wasn’t enough.

“They are not taking responsibility,” Guo said. “They can’t let such a dangerous man free merely because China won’t take him.”

No warning for victims

Long after her assailant went off to prison, Qian Wu kept an eye out for him in her Flushing, N.Y., neighborhood, scanning the crush of pedestrians flowing into the markets, the take-out joints, and the massage parlors nearby. She quizzed the fruit vendors on the street. Nobody had seen Huang Chen. Nonetheless, Wu kept a restraining order out against him — just in case.

Wu had a tough exterior, but those close to her said her attitude masked her fear. She was thin and walked with a limp from injuries she suffered in a car accident years ago. She hardly spoke English, and she had fled political repression in China. And until she remarried in 2008, Wu was a woman on her own, running an employment service for immigrants.

“She was disabled, so she had to be tougher than the others,” said Guo.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country at a detention center in El Paso, federal officials were trying to figure out what to do with Chen, a man who could seem normal one moment and mentally unbalanced the next. Immigration officials continued to hold Chen for another year after his 30-day sentence ran out, holding out hope that China would take him back.

When that didn’t happen, an immigration agent dropped Chen off at a local homeless shelter, in April 2008.

But just two months later, El Paso police arrested Chen after he punched two men in a plaza downtown. Then, just days after Chen got out of jail for the assaults, police arrested him again on a disorderly conduct charge for attacking a man on a bicycle right in front of them. Police described him as “a danger” to himself and others in their report.

Chen returned to the El Paso detention center to await deportation, but again China refused to take him back, so in October 2009, immigration officials again released him. This time, he made it clear that he wanted to get back to New York. He blamed Qian Wu for his troubles, court records later showed, and he knew exactly where to find her: Apartment 3F in a building on 40th Road.

When Chen walked through Wu’s unlocked front door for the first time since 2006, she ran downstairs and begged neighbors to call 911. She asked police and prosecutors for help with a new restraining order, since hers had expired, but never managed to get one. Guo warned his wife to stay inside.

One desperate night, Guo recalled, he asked Wu what they should do, and she responded bitterly.

“She said we can just wait to die,” he said.

Most victims, including Wu, have no idea that the criminal who victimized them has been released, based on a Globe analysis of ICE’s little-known victim notification program and the number of immigrants released from its custody. Federal immigration statistics show ICE has released or deported more than 1 million criminals over the past decade, but they have made just 1,000 to 3,000 victim notifications.

Currently, only 336 crime victims are enrolled in ICE’s program, compared with 2.2 million victims in the Justice Department’s electronic notification system in 2010 alone.

Immigration officials say they want more crime victims to sign up for their system, but it’s up to the victims to register. Wu’s widower was unsure whether she had been offered the opportunity to enroll, though he knows she would have been interested.

The Queens district attorney’s office, which handled Chen’s attacks on Wu, said they were not aware of Chen’s release. ICE officials say they are under no obligation to contact law enforcement officials when civil immigration detainees are released, though they do so when officials request it.

In Flushing, court records show, Chen stalked the panicked Wu for days. He moved into the same building, a few doors down. He tried to reach through the metal gate on her door and unlock it. He even took the $200 her husband gave him to go away.

On Jan. 26, 2010, security camera footage showed Chen leaving Wu’s building, his green sweater soaked in blood. Police arrested him at a local hospital seeking treatment for a hand wound.

Chen, now 50, made no secret in court that he wanted to kill Wu as revenge for his long stint in prison. Justice Richard L. Buchter called the murder “cold-blooded and grotesque,” and especially senseless because Chen was not supposed to be here at all.

“I just — I am just disturbed by what you told me regarding the fact that this person should have been deported and was not,” said Buchter, who sentenced Chen to 27 to 29 years in prison.

Wu’s widower has filed claims against ICE and multimillion-dollar lawsuits against the New York City Police Department and Chen.

From his offices in Times Square, lawyer George W. Clarke said Guo’s case is one of the toughest he’s had in years, because immigration officials provide so little information. They ask him questions he said they should answer, such as when they released Chen, and refuse to provide documents.

“They’re not telling us anything,” Clarke said. Later, he added: “I think it’s just the immigration service doesn’t want to be bothered or exposed to liability for releasing people who may be guilty of crimes and who have no right to be here, such as Huang Chen.”

Officials at the Chinese Embassy in Washington did not respond to e-mails and phone calls about Chen’s case.

The whole experience has shaken the Rev. Bill Morton, an El Paso priest who gave Chen a cleaning job when he got out of detention and sometimes drove him to meetings with ICE. Over time, he became concerned about Chen’s mental health and, looking back, he wonders why immigration officials didn’t express similar concerns, or warn volunteers like him.

“I’m totally pro-immigrant, but I’m certainly not pro-ignorance or indifference where you’re exposing criminal people or insane people on an unknowing public,” Morton said. “That’s not helping immigrants or the US or the person themselves.”