The full criminal complaint by the FBI on Federal charges for Ahmad Khan Rahami is here.

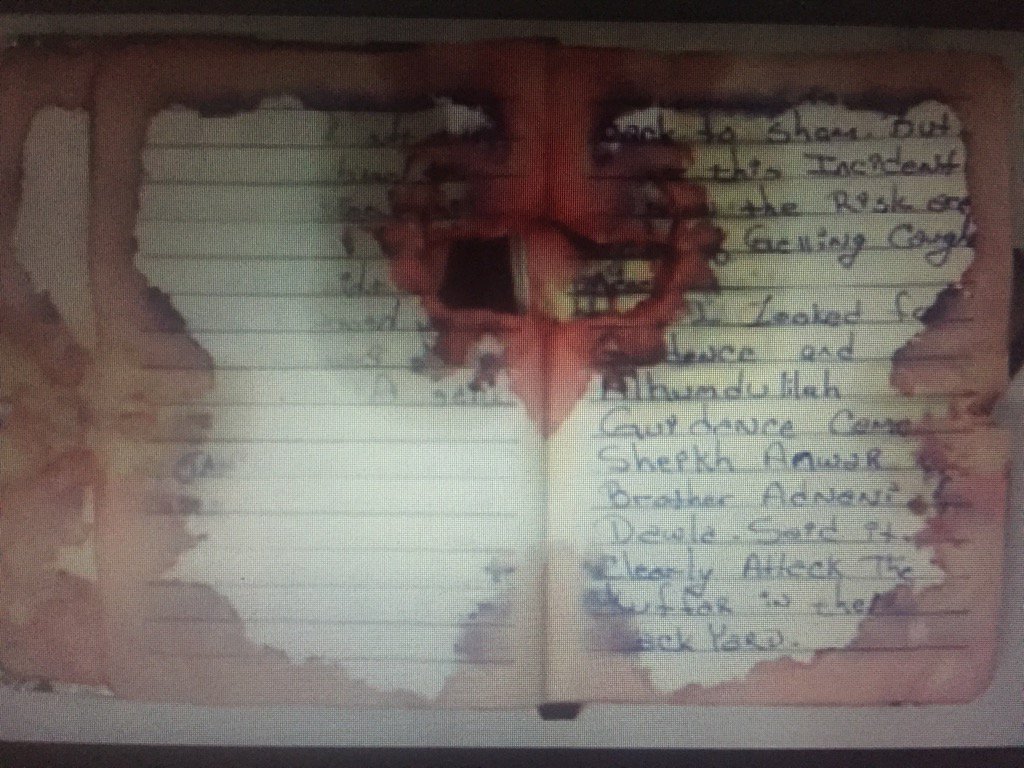

Ahmad kept a journal and it was on his body when he was wounded in a shooting exchange with police near his home.

Much of the references in this journal are to Anwar al Alawki who was an American born cleric and major target for the Obama administration to begin the defeat of al Qaeda. He was in fact killed in a drone strike in Yemen. Major Nadal Hassan, the Ft. Hood killer was also a devoted follower of al Alawki.

This journal does have a very small reference to Islamic State, however Rahami was radicalized during one of his last trips to Afghanistan and Pakistan where the Taliban and al Qaeda maintain a foothold of power. Islamic State on the days of the bombings in New York and New Jersey did not claim any connection however they did to the knife attack in St. Cloud, Minnesota.

There was immediate chatter and concern that there was a functioning terror cell in that does appear to be the case in some form. Rahami did not act alone. The FBI has published a wanted poster for 2 other individuals.

There was immediate chatter and concern that there was a functioning terror cell in that does appear to be the case in some form. Rahami did not act alone. The FBI has published a wanted poster for 2 other individuals.

Rahami’s father brought the family to the United States under asylum conditions and there have been several legal cases with members of the family with law enforcement. Ahmad has a first wife (Dominican) and a daughter and he is known to have married a second wife in Afghanistan and has a child with her. The second wife was returning to the United States and was detained by the FBI in the United Arab Emrites. Ahmad’s father wanted his 8 children to remain loyal to their heritage and such has been the case at least for some. One son moved back to the border region between Afghanistan and Pakistan and the father in fact himself was part of the mujahedeen as a fighter against the Soviets as did Usama bin Ladin.

Not only has the father travel back to Afghanistan but the son, Ahmad did so more than once.

Rahami, 28, spent several weeks in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and Quetta, Pakistan, in 2011, according to a law enforcement official who reviewed his travel and immigration record.

Two years later, in April 2013, he went to Pakistan and remained there until March 2014 before returning to the US, official said.

So, how did the FBI and DHS miss all the signals?

In part from Vocativ: The [FBI] should have launched a formal surveillance investigation as Rahami clearly followed a path towards radicalization and mobilization over the past two years,” said Nicholas Glavin, a senior research associate at the U.S. Naval War College.

Tracking all potential terror threats, however, is not easy. The FBI claims it already has more than 1,000 active Islamic State probes alone, which does not include investigations related to other Islamist groups. And Rahami is by no means the only terror suspect to avoid detection. Analysts who spoke with Vocativ noted that Mohammad Youssef Abdulazeez, the man who killed four marines at a pair of Tennessee military sites in July 2015, had not been monitored by the FBI. Neither had Syed Farook and Tashfeen Malik, the husband and wife who carried out the ISIS-inspired slaughter in San Bernardino, California, last year.

Even those known to law enforcement as would-be jihadists manage to conduct horrific attacks. The FBI had investigated Omar Mateen on two separate occasions before the Florida man executed 49 people and wounded 53 others during a shooting massacre at the Pulse Nightclub in Orlando this summer.

“The U.S. has the most robust counterterrorism apparatus [in the world], yet it is already stretched thin,” Glavin said. FBI Director James Comey previously admitted that his agency has struggled to keep up with surveillance demands.

Experts also concede that there’s no predictable path toward radicalization, making it a persistent challenge to suss out extremists. Some studies have argued that a uniform profile of a “lone-wolf” terrorist does not exist. Peter Bergen, who has researched more than 300 jihadist terrorism cases in the U.S. since 9/11, told Vocativ that they lead largely normal lives.

Bergen’s data shows that four-fifths of these homegrown jihadists are U.S. citizens. They are no more likely to have criminal backgrounds than other Americans and are less likely to suffer from mental illness. Many of them attended college and are married.

“The big takeaway is that they’re ordinary Americans,” Bergen, who published the book The United States of Jihad: Investigating America’s Homegrown Terrorist earlier this year, told Vocativ. Like most, Rahami was not a foreigner, a refugee or a recent immigrant.

Which presents a daunting challenge of its own.

“We’ve created political culture where we want 100 percent success in stopping them,” Bergen said. “Unfortunately, that is not a realistic expectation.”

Judge blasts State Dept for slow-walking Hillary emails

SMOKING GUN: “BleachBit” Paul Combetta ASKED TO STRIP OR REPLACE VIP’s EMAIL ADDRESS! https://redd.it/2bmm4l

#MAGAThe electronic exchange as noted here.

[–]GateheaD 1 point2 points3 points (0 children)